Unit

Years: 1830-1860s

Culture & Community

Economy & Society

Freedom & Equal Rights

Historical Events, Movements, and Figures

Prior to this lesson, students should be aware of the institution of slavery in the United States and its economic implications on the American economy in both the North and the South. Students should also be aware of the conflicting ideals of founding documents such as the Declaration of Independence and the actual lived experiences of African Americans. Finally, students should be knowledgeable about the variety of ways that enslaved African Americans sought freedom in response to this injustice.

You may want to consider after teaching this lesson:

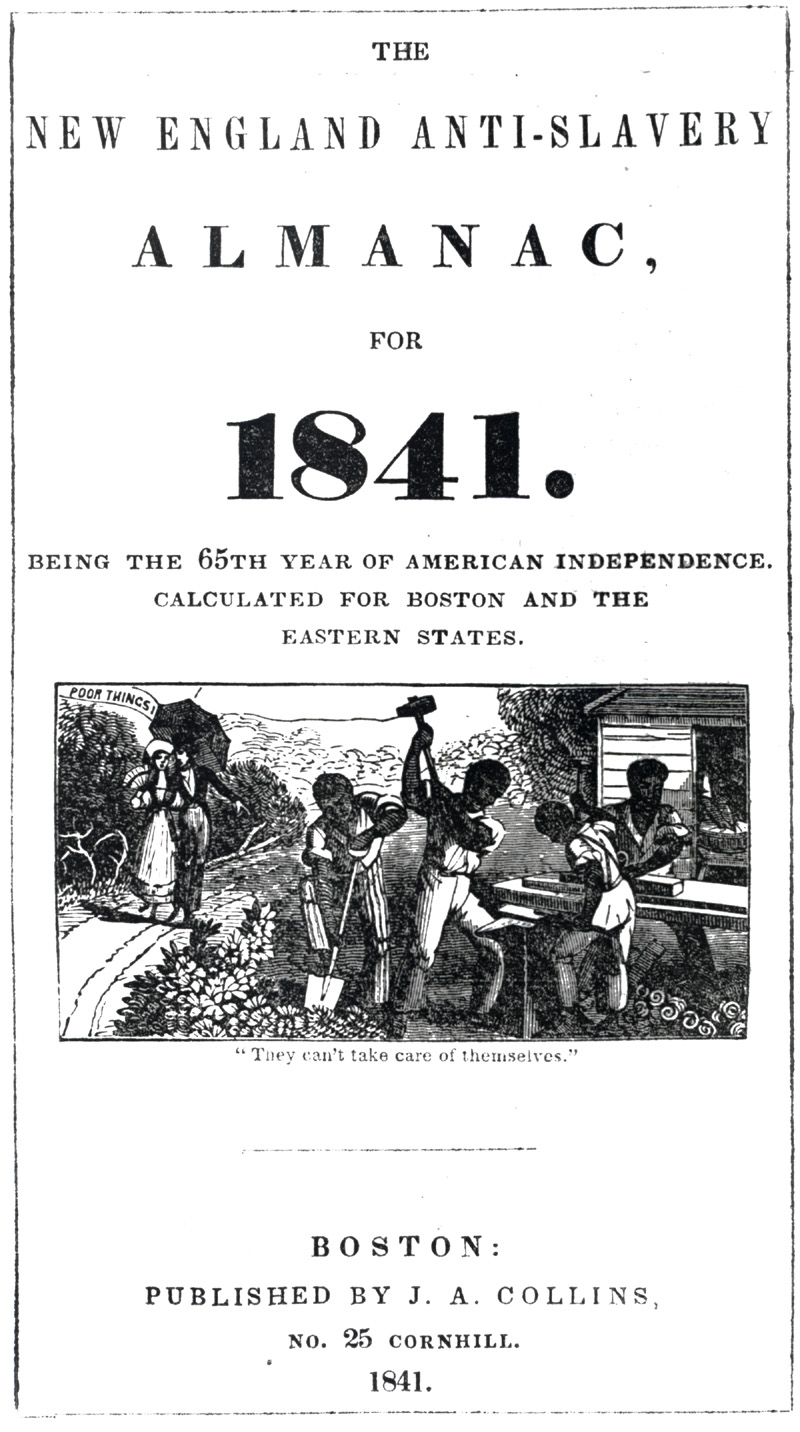

Abolitionists are examples of some of the earliest social justice activists in American history who worked towards ending slavery. Propaganda, which refers to information that is spread with the aim of promoting a particular cause or point of view, was a frequent tool used by abolitionists in their fight. While abolitionists often addressed audiences through published essays or public speaking engagements, they also used many other venues and approaches to issue their calls for action. While the efforts of abolitionists may not have represented the same risks as other approaches, the sources in this unit show that being an activist took many different successful forms during this period. Further, the approaches led to modern day implications for how we use propaganda today to popularize social issues and inequities.

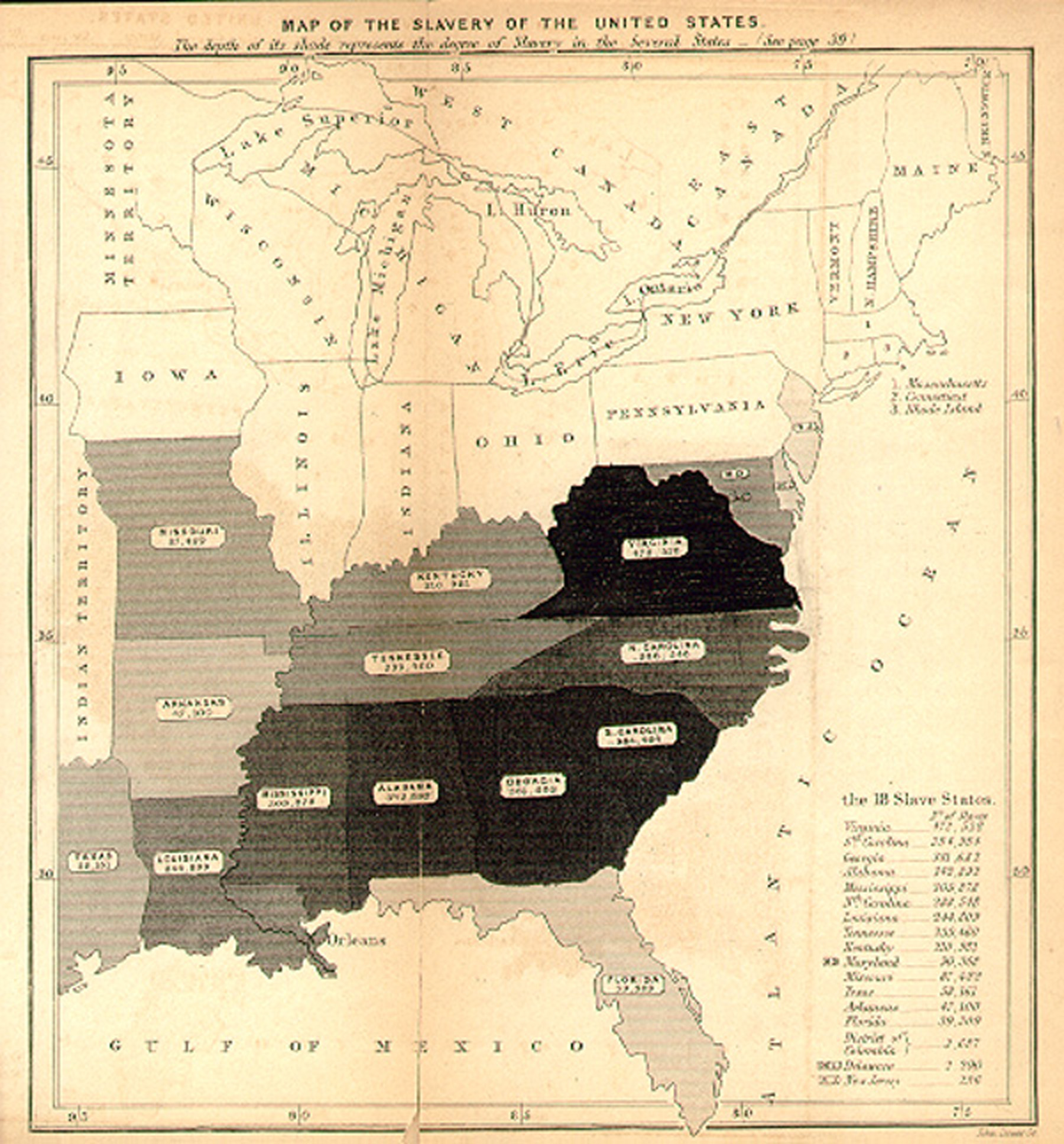

The founding of the United States contained a fundamental paradox between the ideals professed by founding documents such as the Declaration of Independence and the actual lived reality for African Americans. While it was stated that all men are created equally and have rights to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness the institution of slavery refuted that. And as the Southern economy was built on the foundation of slavery and Northern states also benefited from it economically, there was for many no impetus to address this discrepancy.

Abolitionists are examples of some of the earliest social justice activists in American history who did work towards ending slavery. The Abolition Movement started with a focus on abolishing the international slave trade between the 1790s and 1808. Once this goal was accomplished, activists focused their attention on ending slavery entirely throughout the nation.

Abolitionists were very active in the years leading up to the Civil War, but they made up a minority opinion and it was often very dangerous to espouse ideas of equality. While, the highest urgency and largest scope of efforts to seek and make freedom attainable resided within free and enslaved Black Americans, White abolitionists, such as William Lloyd Garrison, often influenced by Christian morals made it an interracial movement.

Abolitionists took action in a multitude of ways. For example, some abolitionists risked their lives by helping enslaved Americans escape from slavery through the Underground Railroad. While others wrote and published their stories and opinions about the institution of slavery evoking passionate responses in their audiences. David Walker, Harriet Jacobs, Sojourner Truth, Frederick Douglass and William Lloyd Garrison all had seminal works or speeches during this time that impacted a great many Americans’ understanding of the brutality of slavery as well as how the institution of slavery was contrary to the American values of freedom and democracy.

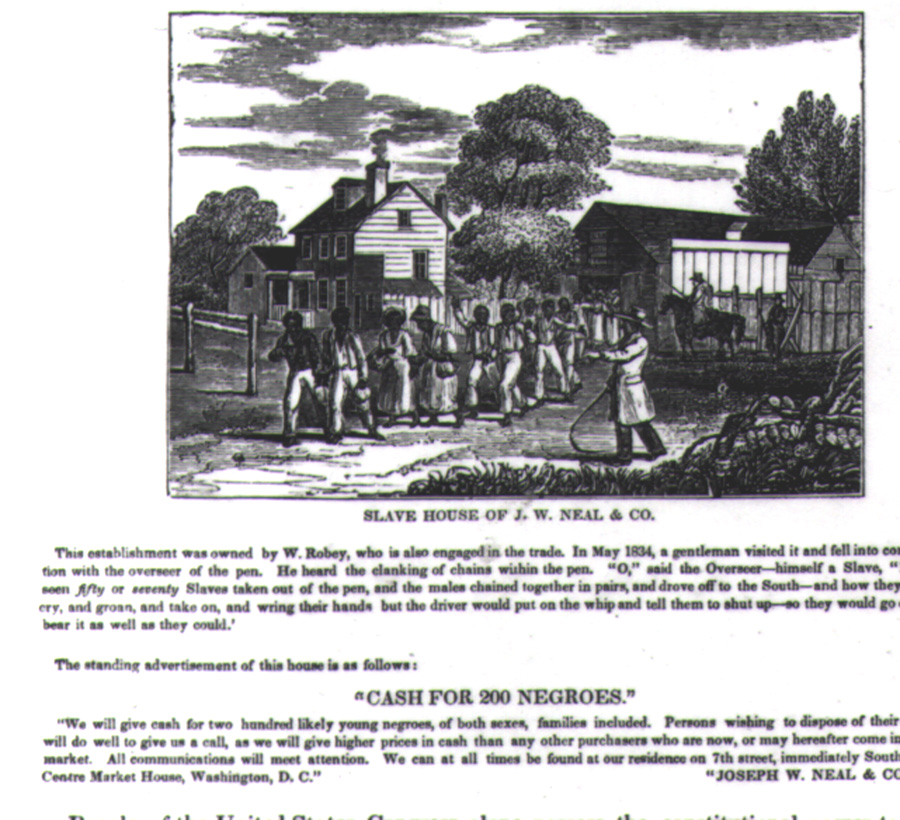

Many abolitionists however were not able or willing to commit to such dangerous or public acts of support and found other ways to raise awareness to turn the tide of public opinion. In contrast to potentially dangerous actions like sheltering people escaping from slavery, the publication and sharing of books, newspapers, images and songs could easily be incorporated into a person’s private life. These materials were still able to express the horrors of slavery, but targeted a larger audience including children and youth and illiterate adults, to garner greater public support. Further, readers, people who read aloud to groups in barbershops, churches and other places, also reached those who could not read.

As abolitionists began finding new and unique ways to reach their intended audiences, the country was beginning to show major signs of strain over the issue of slavery. Many abolitionists began to understand that war might be the only way to abolish the institution of slavery in the United States. Events like the Missouri Compromise, the Compromise of 1850, the Fugitive Slave Law, and the Kansas Nebraska Act would eventually lead the country to engage in the Civil War.

If you would like to learn more about the language of slavery, the National Park Service has a wonderful resource you can access- https://www.nps.gov/subjects/undergroundrailroad/language-of-slavery.htm

Barnes, Michael Randall (2021). Positive Propaganda and The Pragmatics of Protest. In Brandon Hogan, Michael Cholbi, Alex Madva & Benjamin S. Yost (eds.), The Movement for Black Lives: Philosophical Perspectives. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 139-159.

Cameron, Christopher. The Abolitionist Movement: Documents Decoded. United States: ABC-CLIO, 2014.

Douglass, Frederick. Narrative of the life of Frederick Douglass: An American slave, written by himself. Harvard University Press, 2009.

Fox-Amato, Matthew. Exposing Slavery: Photography, Human Bondage, and the Birth of Modern Visual Politics in America. Oxford University Press, 2019.

Harrold, Stanley. American abolitionists. Routledge, 2014.

Jeffrey, Julie Roy. The great silent army of abolitionism: Ordinary women in the antislavery movement. Univ of North Carolina Press, 1998.

Lowance, Mason, ed. Against Slavery: An Abolitionist Reader. Penguin, 2000.

Mayer, Henry. All on fire: William Lloyd Garrison and the abolition of slavery. WW Norton & Company, 2008.

Masur, Kate. Until Justice Be Done: America’s First Civil Rights Movement, from the Revolution to Reconstruction. WW Norton & Company, 2021.

Sinha, Manisha. The slave’s cause: A history of abolition. Yale University Press, 2016.

Spires, Derrick R. The Practice of Citizenship: Black Politics and Print Culture in the Early United States. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2019.

Stowe, Harriet Beecher. Uncle Tom’s Cabin: 1852. Tauchnitz, 1852.

Williams, R. Owen. Encyclopedia of Antislavery and Abolition [Two Volumes]. United Kingdom: Greenwood Press, 2006.

Abolition. African American Mosaic. American Memory Collection. Library of Congress, Washington. D.C. www.loc.gov/exhibits/african/afam005.html

From Slavery to Freedom: the African American Pamphlet Collection, 1824-1909. American Memory Collection, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/aapchtml/aapchome.html

Slavery and Abolition. Guide to Primary Sources. Boston Public Library. Boston, MA. https://guides.bpl.org/primarysources/slaveryandabolition

Abolition. Resources “The Age of Reform”. TeachUShistory.org. American Antiquarian Society. Worcester, MA. https://www.teachushistory.org/second-great-awakening-age-reform/resources Scroll down a little ways to “Abolition” for an incredible collection of primary sources.

Abolitionists are examples of some of the earliest social justice activists in American history. It is important to help students understand that the antislavery movement was interracial and diverse. African Americans clearly had the most urgency for freedom and equality and as such, both free and enslaved African Americans, created, led and sustained the movement. Yet, exploring the ways that abolitionists worked to spread their message is also a chance to understand and stress that while most White Americans did accept the institution of slavery as a “necessary evil”, there was a small, but passionate, group who understood that the institution of slavery was contrary to the American values of freedom and democracy.

It is important throughout this unit to keep in mind your choice of vocabulary in describing African Americans during this period in history. For example, there are many sources which use the historical term “fugitive” to describe an enslaved person that has “escaped” or “run away”. There is a growing movement to recognize the power of words historians and teachers use in their work. In the case of “fugitive slaves” an alternative is to adopt the term “freedom seeker.” This shift in vocabulary moves the focus away from an association with criminal behavior to a recognition that enslaved people were not criminals, but rather were trying to escape a cruel and unjust system. If you would like to learn more about the language of slavery, the National Park Service has a wonderful resource you can access through the Further Resources in this unit.

Several of the sources in this lesson also contain racist language or images that may be disturbing to students. It is imperative that these be shared with students with great care, as they can trigger painful emotions in students, such as anger, sadness, fear, and shame. African American students may feel that their identity is under attack. Be sure to create or revisit classroom expectations for behavior that are grounded in respect and empathy for all and provide clear expectations for how students should engage with this content. It is also important to inform students before sharing any potentially disturbing source materials. Offer a clear rationale for why you are sharing the source and allow individual students to opt out of engaging with the source- offering them a meaningful alternative activity.

Many of the primary sources will also use words that students may be unfamiliar with. Provide access to a dictionary to encourage students to look up words that they do not know.

Abolitionists as the name implies strive for the complete eradication of practices rather than incremental reforms. In the 18th and 19th century, abolitionists who were advocates for the abolition of slavery took action in a multitude of ways. There were abolitionists that risked their lives by helping those enslaved seek freedom through the Underground Railroad. While others publicly wrote or spoke out against slavery. By identifying key venues in order to issue their calls for action a wider audience could be reached.

There were countless other abolitionists that were unable to commit to such dangerous or public acts of support that were still an important part of the movement. Sharing songs, articles, art and even the act of reading aloud for those who were unable to were efforts that could easily be incorporated into a person’s private life. These types of tactics were not only successful in the abolition movement but have also since been utilized in other social justice causes because of the wider audiences they were able to reach.

Select the activities and sources you would like to include in the student view and click “Launch Student View.”

It is highly recommended that you review the Teaching Tips and sources before selecting the activities to best meet the needs and readiness of your students. Activities may utilize resources or primary sources that contain historical expressions of racism, outdated language or racial slurs.

This unit’s primary sources are considered propaganda. This activity explores the use of the term propaganda and assesses it as a social activist tool both past and present.

Propaganda refers to information used to promote or publicize a particular political cause or point of view. Propaganda can take various forms, such as posters, advertisements, speeches, or social media campaigns, and it is commonly used by governments, organizations, or individuals to influence public opinion or behavior.

Historians often refer to the materials that abolitionists produced as “propaganda.” This presents an interesting interpretation to the materials because typically, the term propaganda carries a negative connotation around – the intent to mislead the audience. Yet, not all propaganda is created equally. There are many examples of “positive propaganda” that complicate the typical definition. For example, governments use propaganda to promote healthy habits such as no smoking campaigns and attempting to reduce drunk driving. Propaganda can also be used to raise morale during wartime. More recently, there has also been a movement by scholars to consider protest propaganda such as Black Lives Matter as positive propaganda due to its goal in creating a more equitable society.

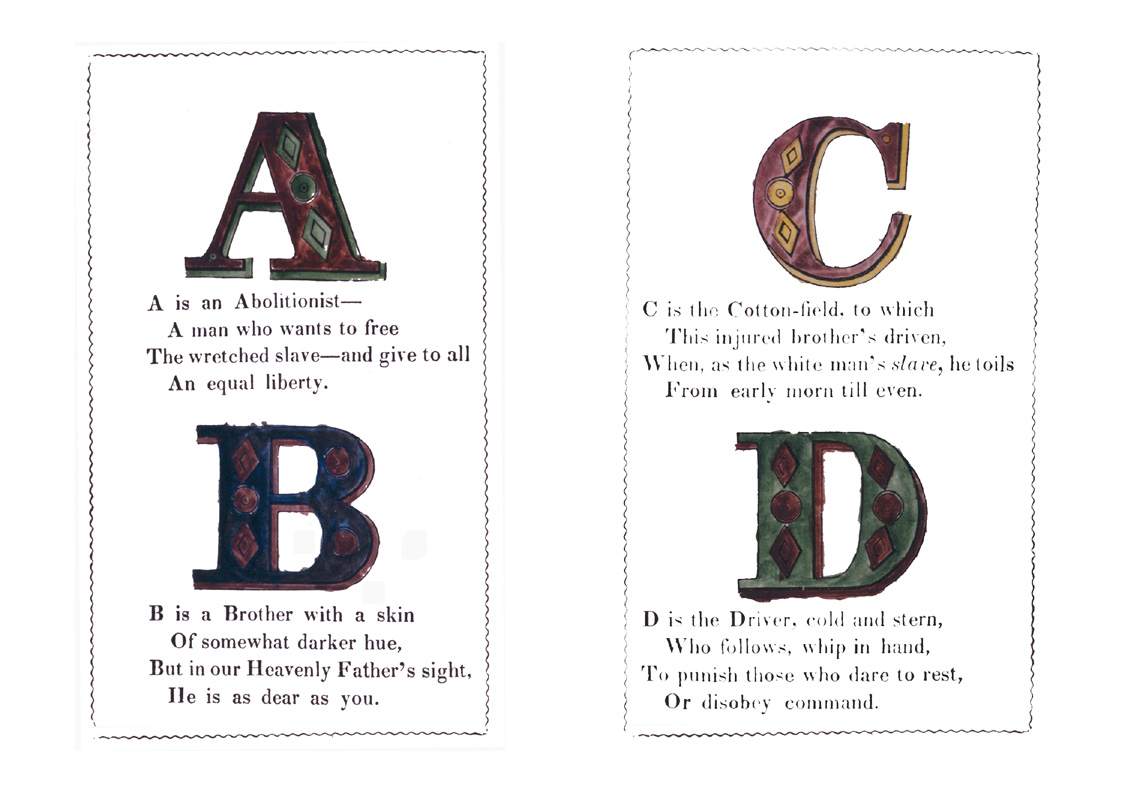

The Anti Slavery Alphabet

Philadelphia

Printed for the Anti Slavery Fair 1847

Merrihew&Thompson printers.

To Our Little Readers:

Listen little children, all,

Listen to our earnest call:

You are very young, ‘tis true,

But there’s much that you can do.

Even you can plead with men

That they buy slaves not again.

And those they have may be

Quickly set at liberty.

They may hearken what you say,

Though from us they turn away.

Sometimes when from school you walk,

You can with your playmates talk,

Tell them of the slave child’s fate,

Motherless and desolate.

And you can refuse to take

Candy, sweetmeat, pie or cake,

Saying “no”-unless ‘tis free-

“the slave shall not work for me.”

Thus, dear little children, each

May some useful lesson teach;

Thus each one may help to free

This fair land from slavery.

A is an Abolitionist—

A man who wants to free

The wretched slave—and give to all

An equal liberty.

B is a Brother with a skin

Of somewhat darker hue,

But in our Heavenly Father’s sight,

He is as dear as you.

C is the Cotton-field to which,

This injured brother’s driven,

When as the white man’s slave he toils

From early morn till even.

D is the Driver, cold and stern,

Who follows whip in hand,

To punish those who dare to rest,

Or disobey command.

E is the Eagle soaring high;

An emblem of the free;

But while we chain our brother man,

Our type he cannot be.

F is the heart sick Fugitive,

The slave who runs away

And travels through the dreary night,

But hides himself by day.

G is the Gong, whose rolling sound,

Before the morning light,

Calls up the little sleeping slave,

To labor until night.

H is the Hound his master trained,

And called to scent the track,

Of the unhappy fugitive,

And bring him trembling back.

I is the Infant, from arms

Of its fond mother torn,

And, at a public auction, sold

With horses, cows, and corn.

J is the Jail, upon whose floor

That wretched mother lay,

Until her cruel master came,

And carried her away.

K is the Kidnapper, who stole

That little child and mother—

Shrieking, it clung around her, but

He tore them from each other.

L is the Lash that brutally

He swung around its head,

Threatening that “if it cried again,

He’d whip it till ‘twas dead.”

M is the Merchant of the North,

Who buys what slaves produce—

So they are stolen, whipped and worked,

For his, and for our use.

N is the Negro rambling free

In his far and distant home,

Delighting ‘neath the palm trees’ shade

And cocoa nut to roam.

O is the Orange tree that bloomed

Beside his cabin door,

When white men stole him from his home

To see it never more.

P is the Parent, sorrowing,

And weeping all alone—

The child he loved to lean upon,

His only son, is gone!

Q is the Quarter where the slave

On coarsest food is fed,

And where with toil sorrow worn,

He seeks his wretched bed.

R is the “Rice Swamp, dank and lone,”

Where, weary day by day,

He labors till the fever wastes

His strength and life away.

S is the Sugar, that the slave

Is toiling hard to make,

To put into your pie and tea,

Your candy and your cake.

T is the rank Tobacco plant,

Raised by slave labor too:

A poisonous and nasty thing,

For gentlemen to chew.

U is for Upper Canada,

Where the poor slave has found

Rest after all his wanderings,

For it is British ground!

V is the Vessel in whose dark,

Noisome, and stifling hold,

Hundreds of Africans are packed,

Brought o’er the seas and sold.

W is the Whipping post,

To which the slave is bound,

While on his naked back the lash

Makes many a bleeding wound.

X is for Xerxes famed of yore;

A warrior stern was he

He fought with swords; let truth and love

Our only weapons be.

Y is for Youth—the time for all

Bravely to war with sin;

And think not it can ever be

Too early to begin.

Z is a Zealous man, sincere,

Faithful just and true

And earnest pleader for the slave—

Will you not be so too?

Source: The Anti-Slavery Alphabet printed for the Anti-Slavery Fair in Philadelphia (1847)

Music is a language that crosses race and class reaching a wide range of audience. Songs are memorable and can be retold over and over again. In the early to mid-1800s, printing materials would have been expensive and many Americans were not literate. Songs could be memorized and repeated regardless of literacy. Songs could also be used in informal settings to share important messages. For these reasons, songs were an important tool in spreading the abolitionist message. Many of these songs are used to uplift abolitionists in their work towards ending slavery. They could appeal to existing abolitionists or to Americans who want to be a part of something greater than themselves. This was true across regions as even enslaved populations could share songs in secret and the religious undertones were intended to be hopeful.

The songs we read today were meant to evoke emotion from their audience. Songs like “I am an Abolitionist” might make someone feel proud of their identity and for fighting against slavery. The songs were intended to inspire the listener to act and protest the laws that held African Americans in bondage. They might also have inspired a feeling of righteousness through the religious overtones. A song like “Ye Sons of Freemen” might have evoked excitement and even anger with lines referring to burning down plantations. Many of the lyrics might have also provoked a feeling of injustice in the violence and unfairness that the system of slavery produces.

We have many injustices that have been present in our society in the twentieth and twenty-first century. More recent examples of propaganda songs include antiwar music from the 1970s from artists such as Bob Dylan and Marvin Gay, anti-police/anti-government groups such as Rage Against the Machine and N.W.A in the 1990s, and more recent examples such as John Legend and Common’s song “Glory” in 2015.

Document 3.11.1: Lyrics for “I am an Abolitionist,” “Spirit of Freemen, Wake,” and “Ye Sons of Freemen”

I am an Abolitionist!

I glory in the name

Through now by Slavery’s minions hiss’d

And covered o’er with shame

It is a spell of light and power—

The watchword of the free:--

Who spurns it in the trial hour,

A craven soul is he!

I am an Abolitionist!

Then urge me not to pause

For joyfully I do enlist

In FREEDOM’S sacred cause

A nobler strife the world ne’er saw,

Th’enslaved to disenthrall;

I am a soldier for the war,

Whatever may befall!

I am an Abolitionist!

Oppression’s deadly foe;

In God’s great strength I will resist,

And lay the monster low;

In God’s great name I do demand,

To all be freedom given,

That peace and joy may fill the land,

And songs go up to Heaven!

I am an Abolitionist!

No threats shall awe my soul,

No perils cause me to desist,

No bribes my nets control;

A freeman shall I live and die,

In sunshine and in shade,

And raise my voice for liberty,

Of naught on earth afraid.

Spirit of Freemen, wake;

No truce with Slavery make,

Thy deadly foe;

In fair disguises dressed,

Too long hast thou caress’d

The serpent in thy breast,

Now lay him low.

Must e’en the press be dumb?

Must truth itself succumb?

And thoughts be mute?

Shall law be set aside,

The right of prayer denied,

Nature and God decried,

And man called brute?

What lover of her fame

Feels not this country’s shame,

In this dark hour?

Where are the patriots now,

Of honest heart and brow,

Who scorn the neck to bow,

To Slavery’s power?

Sons of the Free! We call

On you, in field and hall,

To rise as one;

Your heaven-born rights maintain,

Nor let oppression’s chain

On human limbs remain;--

Speak! And tis done.

Ye sons of freeman wake to sadness

Hark! Hark, what myriads bid you rise;

Three millions of our race in madness

Break out in wails, in bitter cries

Break out in wails, in bitter cries,

Must men whose hearts now bleed with anguish,

Yes, trembling slaves in freedom’s land,

Endure the lash, nor raise a hand?

Must nature ‘neath the whip-cord languish?

Have pity on the slave,

Take courage from God’s word;

Pray on, pray on, all hearts resolved—these captives shall be free.

The fearful storm—it threatens lowering,

Which God in mercy long delays;

Slaves yet may see their masters cowering,

While whole plantations smoke and blaze!

While whole plantations smoke and blaze;

And may we now prevent the ruin,

Ere lawless force with guilty stride,

Shall scatter vengeance far and wide—

With untold crimes their hands imbruing.

Have pity on the slave;

Take courage from God’s word;

Pray on, Pray on, all hearts resolved—these captives shall be free.

With luxury and wealth surrounded,

The southern masters proudly dare,

With thirst of gold and power unbounded,

To mete and vend God’s light and air!

To mete and vend God’s light and air;

Like beasts of burden, slaves are loaded,

Till life’s poor toilsome day is o’er;

While they in vain for right implore;

And shall they longer still be goaded?

Have pity on the slave;

Take courage from God’s word;

Pray on, pray on, all hearts resolved—these captives shall be free.

O liberty! Can man o’er bind thee?

Can overseers quench thy flame?

Can dungeons, bolts, or bars confine thee,

Or threats thy Heaven-born spirit tame?

Or threats thy Heaven-borne spirit tame?

Too long the slave has groaned, bewailing

The power these heartless tyrants wield;

Yet free them not by sword or shield,

For with men’s hearts they’re unavailing;

Have pity on the slave;

Take courage from God’s word;

Pray on, pray on, all hearts resolved—these captives shall be free.

Source: Anti-Slavery Harp: A Collection of Songs for Anti-Slavery Meetings, Compiled by William W. Brown, A Fugitive Slave, Boston: Bela Marsh, 1848.

Distribute the following documents at work stations around the room.

Allow students to move through the stations, to meet your time constraints, but it is recommended to have at least 8-10 minutes per station. Students, should consider the following questions as they analyze the documents:

In 1845, the American Anti-Slavery Society published a thirty-six-page pamphlet, which included, among other things, its declaration of sentiments, excerpted here, its platform, a discussion of immediate abolition, and a piece titled, “The Influence of Slavery.”

ADOPTED AT THE FORMATION OF SAID SOCIETY, IN PHILADELPHIA, OF THE 4TH DAY OF DECEMBER, 1833.

The Convention, assembled in the city of Philadelphia, to organize a National Anti-Slavery Society, promptly seize the opportunity to promulgate the following DECLARATION OF SENTIMENTS, as cherished by them, in relation to the enslavement of one sixth portion of the American people.

More than fifty-seven years have elapsed since a band of patriots convened in this place to devise measures for the deliverance of this country from a foreign yoke. The corner-stone upon which they founded the Temple of Freedom was broadly this—"that all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights; that among these are life, LIBERTY, and the pursuit of happiness." At the sound of their trumpet-call, three millions of people rose up as from the sleep of death, and rushed to the strife of blood; deeming it more glorious to die instantly as freemen, than desirable to live one hour as slaves. They were few in number—poor in resources; but the honest conviction that Truth, Justice, and Right were on their side, made them invincible.

We have met together for the achievement of an enterprise without which that of our fathers is incomplete, and which, for its magnitude, solemnity, and probable results upon the destiny of the world, as far transcends theirs as moral truth does physical force.

In purity of motive, in earnestness of zeal, in decision of purpose, in intrepidity of action, in steadfastness of faith, in sincerity of spirit, we would not be inferior to them.

Their principles led them to wage war against their oppressors, and to spill human blood like water, in order to be free. Ours forbid the doing of evil that good may come, and lead us to reject, and to entreat the oppressed to reject, the use of all carnal weapons for deliverance from bondage; relying solely upon those which are spiritual and mighty through God to the pulling down of strongholds.

Their measures were physical resistance—the marshaling in arms—the hostile array—the mortal encounter. Ours shall be such only as the opposition of moral purity to moral corruption—the destruction of error by the potency of truth-—the overthrow of prejudice by the power of love—and the abolition of slavery by the spirit of repentance.

Their grievances, great as they were, were trifling in comparison with the wrongs and sufferings of those for whom we plead. Our fathers were never slaves—never bought and sold like cattle—never shut out from the light of knowledge and religion—never subjected to the lash of brutal taskmasters.

But those for whose emancipation we are striving—constituting, at the present time, at least one sixth part of our countrymen—are recognized by the law, and treated by their fellowbeings, as marketable commodities, as goods and chattels, as brute beasts; are plundered daily of the fruits of their toil, without redress—really enjoying no constitutional nor legal protection from licentious and murderous outrages upon their persons; are ruthlessly torn asunder—the tender babe from the arms of its frantic mother—the heart-broken wife from her weeping husband—at the caprice or pleasure of irresponsible tyrants. For the crime of having a dark complexion, they suffer the pangs of hunger, the infliction of stripes, and the ignominy of brutal servitude. They are kept in heathenish darkness by laws expressly enacted to make their instruction a criminal offense.

These are the prominent circumstances in the condition of more than two millions of our people, the proof of which may be found in thousands of indisputable facts, and in the laws of the slaveholding States.

Hence we maintain, that in view of the civil and religious privileges of this nation, the guilt of its oppression is unequaled by any other on the face of the earth; and, therefore,

That it is bound to repent instantly, to undo the heavy burdens, to break every yoke, and to let the oppressed go free.

We further maintain, that no man has a right to enslave or imbrute his brother—to hold or acknowledge him, for one moment, as a piece of merchandise—to keep back his hire by fraud—or to brutalize his mind by denying him the means of intellectual, social, and moral improvement.

The right to enjoy liberty is inalienable. To invade it is to usurp the prerogative of Jehovah. Every man has a right to his own body—to the products of his own labor—to the protection of law, and to the common advantages of society. It is piracy to buy or steal a native African, and subject him to servitude. Surely the sin is as great to enslave an American as an African.

Therefore, we believe and affirm, That there is no difference, in principle, between the African slave-trade and American slavery.

That every American citizen who retains a human being in involuntary bondage as his property, is, according to Scripture (Ex. xxi. 16), a MAN-STEALER.

That the slaves ought instantly to be set free, and brought under the protection of law.

That if they lived from the time of Pharaoh down to the present period, and had been entailed through successive generations, their right to be free could never have been alienated, but their claims would have constantly risen in solemnity.

That all those laws which are now in force admitting the right of slavery, are therefore before God utterly null and void; being an audacious usurpation of the Divine prerogative, a daring infringement on the law of nature, a base overthrow of the very foundations of the social compact, a complete extinction of all the relations, endearments, and obligations of mankind, and a presumptuous transgression of all the holy commandments; and that, therefore, they ought instantly to be abrogated.

We further believe and affirm—That all persons of color who possess the qualifications which are demanded of others, ought to be admitted forthwith to the enjoyment of the same privileges, and the exercise of the same prerogatives, as others; and that the paths of preferment, of wealth, and of intelligence, should be opened as widely to them as to persons of a white complexion.

We maintain that no compensation should be given to the planters emancipating the slaves—

Because it would be a surrender of the great fundamental principle that man cannot hold property in man;

Because SLAVERY IS A CRIME, AND THEREFORE IS NOT AN ARTICLE TO BE SOLD;

Because the holders of slaves are not the just proprietors of what they claim; freeing the slaves is not depriving them of property, but restoring it to its rightful owners; it is not wronging the master, but righting the slave—restoring him to himself;

Because immediate and general emancipation would only destroy nominal, not real property; it would not amputate a limb or break a bone of the slaves; but, by infusing motives into their breasts, would make them doubly valuable to the masters as free laborers; and

Because, if compensation is to be given at all, it should be given to the outraged and guiltless slaves, and not to those who have plundered and abused them.

We regard as delusive, cruel, and dangerous, any scheme of expatriation which pretends to aid, either directly or indirectly, in the emancipation of the slaves, or to be a substitute for the immediate and total abolition of slavery.

We fully and unanimously recognize the sovereignty of each State to legislate exclusively on the subject of the slavery which is tolerated within its limits; we concede that Congress, under the present national compact, has no right to interfere with any of the Slave States in relation to this momentous subject.

But we maintain that Congress has a right, and is solemnly bound, to suppress the domestic slave-trade between the several States, and to abolish slavery in those portions of our territory which the Constitution has placed under its exclusive jurisdiction.

We also maintain that there are, at the present time, the highest obligations resting upon the people of the free States to remove slavery by moral and political action, as prescribed in the Constitution of the United States. They are now living under a pledge of their tremendous physical force, to fasten the galling fetters of tyranny upon the limbs of millions in the Southern States; they are liable to be called at any moment to suppress a general insurrection of the slaves; they authorize the slave-owner to vote on three-fifths of his slaves as property, and thus enable him to perpetuate his oppression; they support a standing army at the South for its protection; and they seize the slave who has escaped into their territories, and send him back to be tortured by an enraged master or a brutal driver. This relation to slavery is criminal and full of danger: IT MUST BE BROKEN UP.

These are our views and principles—these our designs and measures. With entire confidence in the overruling justice of God, we plant ourselves upon the Declaration of our Independence and the truths of Divine Revelation, as upon the Everlasting Rock.

We shall organize Anti-Slavery Societies, if possible, in every city, town, and village in our land.

We shall send forth agents to lift up the voice of remonstrance, of warning, of entreaty, and rebuke.

We shall circulate, unsparingly and extensively, anti-slavery tracts and periodicals.

We shall enlist the pulpit and the press in the cause of the suffering and the dumb.

We shall aim at a purification of the churches from all participation in the guilt of slavery.

We shall encourage the labor of freemen rather than that of slaves, by giving a preference to their productions; and

We shall spare no exertions nor means to bring the whole nation to speedy repentance.

Our trust for victory is solely in God. We may be personally defeated, but our principles, never. Truth, Justice, Reason, Humanity, must and will gloriously triumph. Already a host is coming up to the help of the Lord against the mighty, and the prospect before us is full of encouragement.

Submitting this DECLARATION to the candid examination of the people of this country, and of the friends of liberty throughout the world, we hereby affix our signatures to it; pledging ourselves that, under the guidance and by the help of Almighty God, we will do all that in us lies, consistently with this Declaration of our principles, to overthrow the most execrable system of slavery that has ever been witnessed upon earth—to deliver our

land from its deadliest curse--to wipe out the foulest stain which rests upon our national escutcheon—and to secure to the colored population of the United States all the rights and privileges which belong to them as men and as Americans—come what may to our persons, our interests, or our reputation—whether we live to witness the triumph of LIBERTY, JUSTICE, and HUMANITY, or perish untimely as martyrs in this great, benevolent, and holy cause.

Done at Philadelphia, the 6th day of December, A. D. 1833.

Source: Platform of the American Anti-Slavery Society,” published in New York, 1855.

Full text can be read on the Library of Congress website http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/ampage

Things for the Abolitionist to do:

Work for the free people of color: See that your schools are open to their children and that they enjoy in every respect all the rights to which as human beings they are entitled.

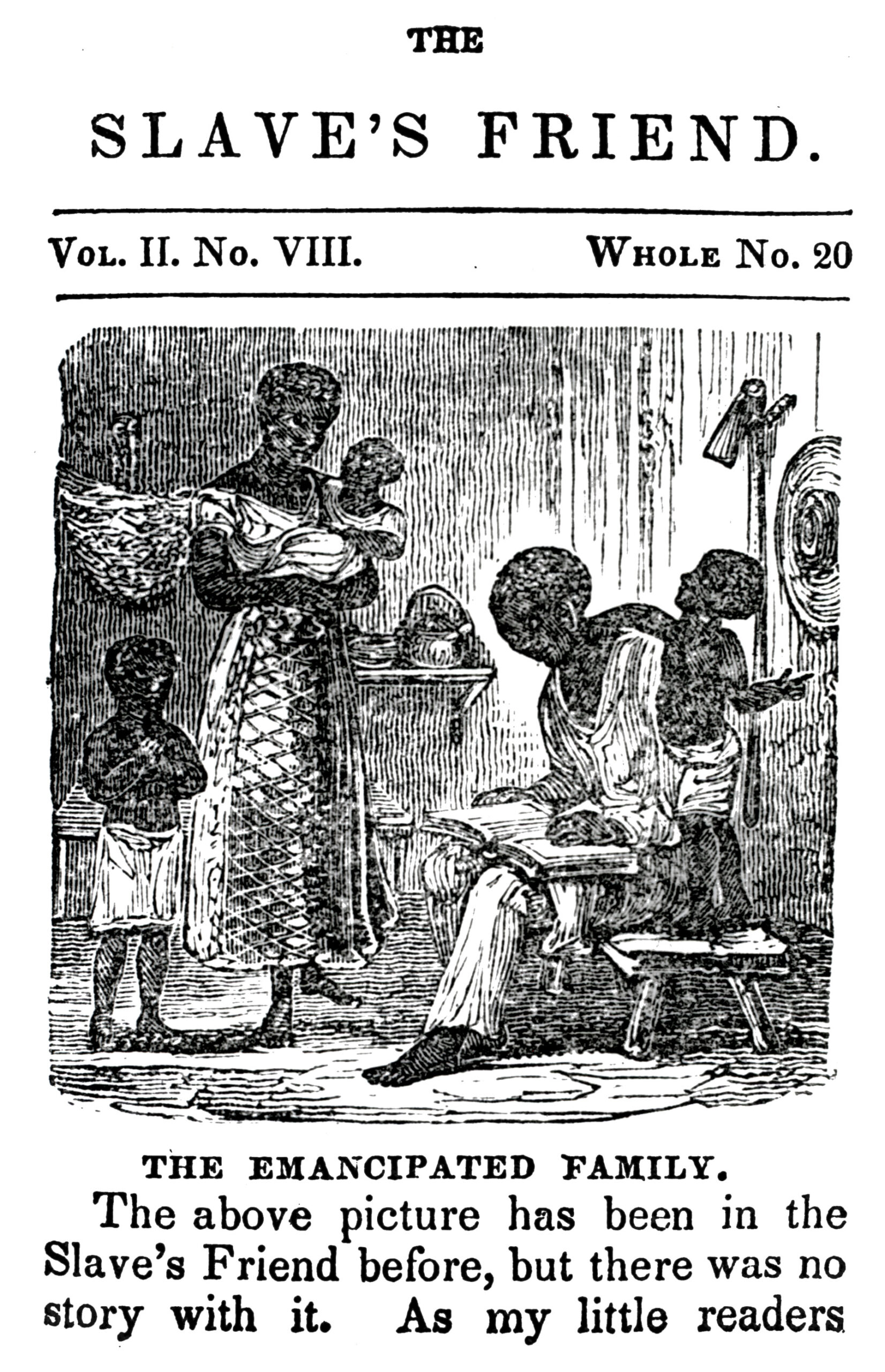

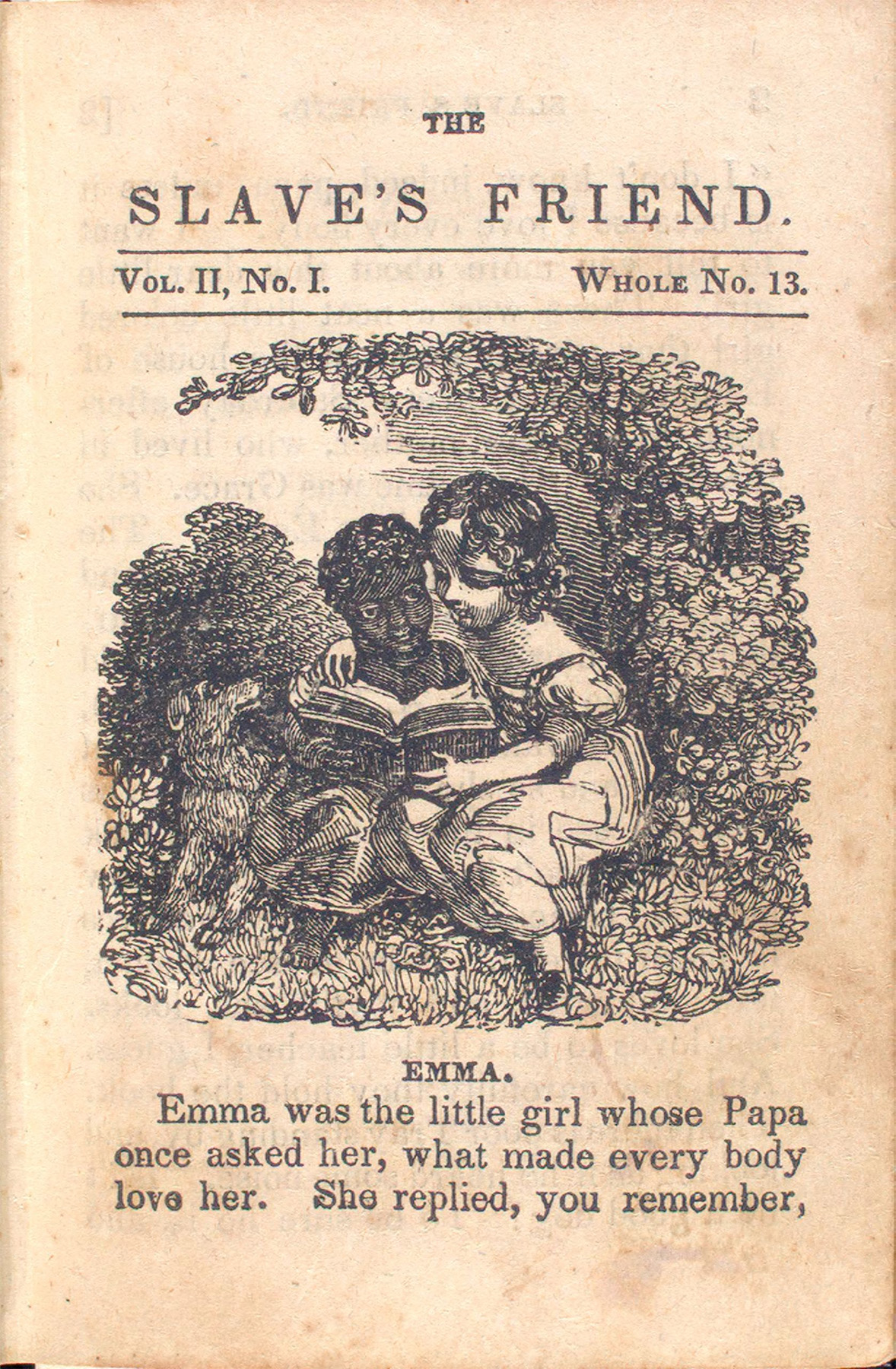

Distribute The Slave’s Friend Print 1, 1836 and The Slave’s Friend Print 2, 1837. Ask students to look for clues that point to how these sources may differ from other sources they have examined (ex. large print, states “little readers”, large image, how family is depicted positively- literate and loving).

After a brief discussion, explain to students that The Slave’s Friend was a periodical written for children, whereas as many of the other sources have been geared to adult audiences. This periodical was published from 1836-1838 by the American Anti-Slavery Society.

Discuss with students the following:

Next, provide resources or allow students independently or in small groups to use learned research skills to find and discuss the following:

Students should select one source covered in this unit that they feel would have been highly effective in bringing about an end to the institution of slavery.

Students should plan and write an essay that includes details about the source (creator, audience, dissemination method, outcome, etc.) and the reasons for their opinion.

To make a connection to today, students can choose a past or contemporary social justice issue and identify a song related to that movement. Ask students to analyze the lyrics and compare and contrast the modern piece they choose with one of the abolitionist songs from Activity 2.

Students can present their findings as a poster or presentation that allows their classmates to hear or read the

Be mindful for student review and presentation that some songs may have parental advisory warnings that should be considered based on age.

Please login or sign up to access the student view functions.