Unit

Years: 1920-1942

Economy & Society

Historical Events, Movements, and Figures

When the Civil War ended, more than four million African Americans who had formerly been enslaved were legally free. Unfortunately, the conclusion of the war did not suddenly change the White Supremacist culture and ideology that existed, particularly in the South. This culture was one of the factors that led to the Great Migration in the early 1900s, during which around six million Black people moved from the American South to Northern, Midwestern, and Western states.

Though fleeing the South did not bring about economic, social or political equality in the years of the Industrial Revolution (1760-1940), there was work to be found as new innovations and industries were formed. One of these was the railroad industry. In 1867, George Pullman, a White cabinetmaker from New York, formed The Pullman Sleeping Car Company in Chicago in order to offer a railway experience that featured luxury sleeping and dining cars.

These sleeping cars were staffed by White Conductors and Black Porters, Maids and Laundresses. Pullman exclusively hired Black staff in these roles and particularly sought dark-skinned people who were formerly enslaved, reasoning that he could pay these workers less for longer hours and capitalize on the expectation of race-based servitude established by the American slave system.

During these same years, labor unions, like the American Federation of Labor (AFL), Knights of Labor (KOL), and National Women’s Trade Union League, began organizing workers to make factory labor safe and sustainable. Labor unions fought for safer working conditions, a minimum wage, an eight-hour work day, and a five-day work week. While some labor unions welcomed all workers, the majority refused to recognize Black workers as members.

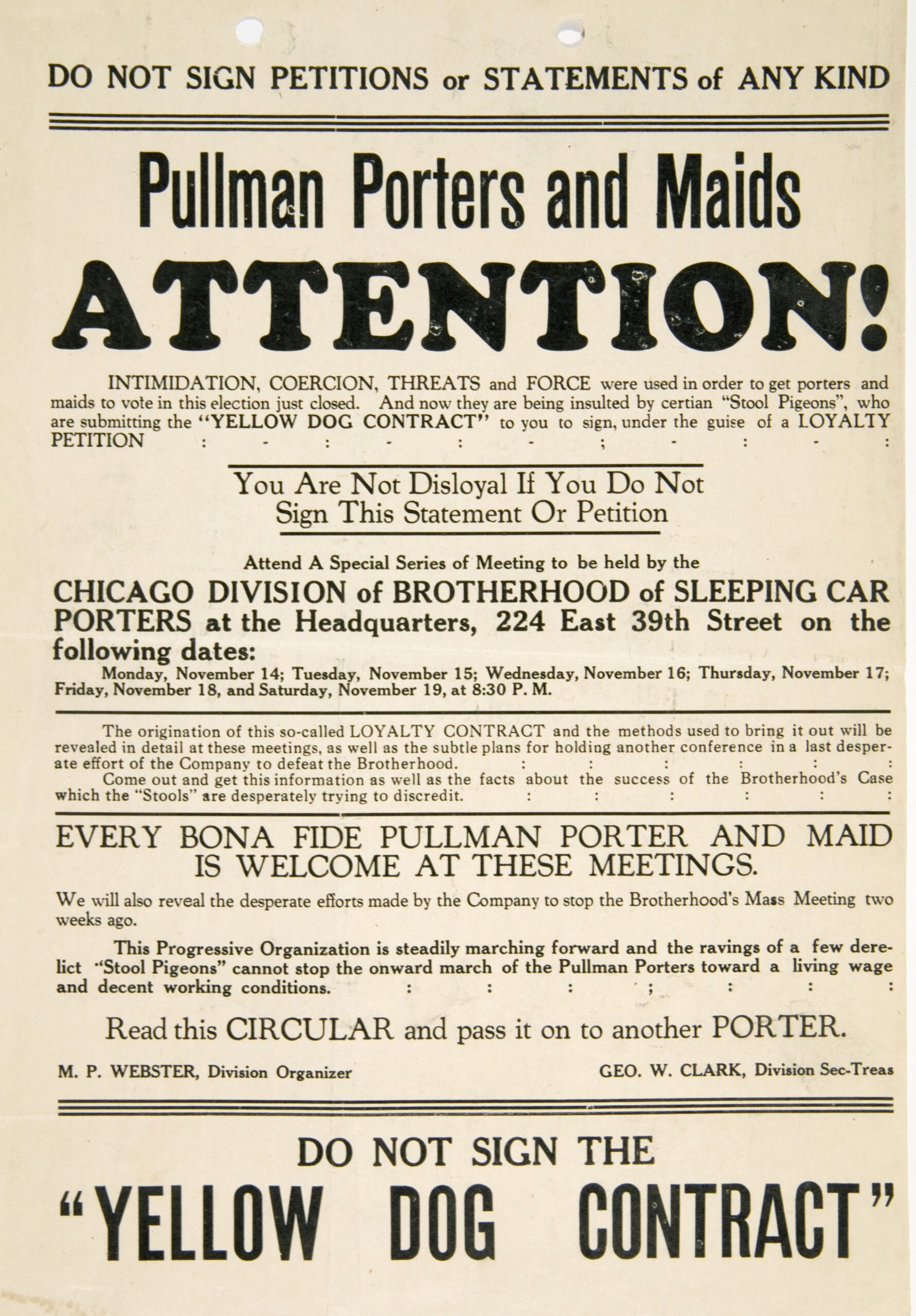

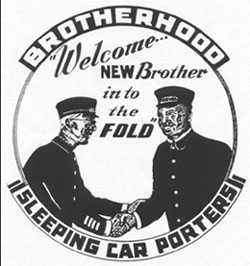

Efforts to create a union for employees working for Pullman are largely credited to A. Philip Randolph. Through a process known as collective bargaining, The Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters was established as the first successful Black trade union in the United States. Randolph was elected its first president in 1925. The union motto was “Fight or Be Slaves.”

Quotes from or about men who worked as porters on Pullman cars

I was able to make a contribution solely because we had the Brotherhood, and I wasn't afraid. And, again, I have to come back to A. Philip Randolph. The Civil Rights Movement saw to it that black people were able to do things legally, like ride on a Pullman car, say. But the labor movement saw to it that black people had the money to buy the ticket to ride on the Pullman cars, see? What good is it to have the right to do something, if you don't have the money to do it? The labor movement gave black people the opportunity to do things that the civil rights movement gave the right to do.

--E.D. Nixon, Pullman porter and organizer of the 1955–56 Montgomery Bus Boycott

My father helped a lot of people who were out of work or had too many children to feed. He’d bring home loads of food that the railroad was going to throw away. That’s how lots of us black people made it down south…helping one another.

--Anderson Betts (son of a Pullman Porter)

When you got off your car you went to the quarters. There’d be maybe a couple hundred porters, maybe, in a place like New York, gathering around in groups, laughing, telling tales, playing cards. Porters act like brothers. If you saw a uniform, you felt like you had a friend. All those porters be together from different districts. You might be in New York, you’d have Kansas city porters, Tampa porters, Jacksonville porters, Boston porters, and sometimes porters were going in all directions and from everywhere. California, San Diego, down there. We have porters sometimes from conventions, going to inaugurations sometimes. There’d be thousands of porters you’d be coming in contact with, hauling people.

--Leon Long, Pullman porter

The black railroad man was a traveling aid society for black people, because when parents had to come [North] to get jobs and finally were able to bring their families, one by one, and establish their homes, most of them traveled under the care of the Railroad man. If youngsters were leaving the South, coming to Boston, they were put on a train in the care of a Pullman porter, or waiter, or cook—whatever the person was the family knew best. The parents knew that the railroad man was going to see that the child ate and was going to reach his destination safely.

--Francena Roberson, Porter organizer interviewed by Robert Hayden

Race workers are the backbone of the Race, and upon their welfare and the advancement of labor depends the progress of all phases of our life, whether religious, social, fraternal, civic or commercial. Hence the problems of the workers are of vital importance to all elements of the group and merit their cooperation and assistance in the efforts towards solutions.

--Milton P. Wenster (Porter), Chicago Defender, December 21, 1929

Source: The quote from E. D. Nixon can be found on http://northbysouth.kenyon.edu/2000/Fraternal/pullman1.htm (Document 5.12.5)

“A Call for the Colored National Labor Union Convention,” 1869

Note: The source refers to Coolie labor. Coolie labor refers to a system in the 19th century where workers, primarily from Asia, were recruited—often under exploitative and coercive contracts—to perform low-wage, physically demanding jobs, typically on plantations, in mines, and in other labor-intensive industries. This labor system emerged as a replacement for enslaved labor after the abolition of slavery.

_______________________________________________________________________________________

Fellow Citizens:—At a State Labor Convention of the Colored Men of Maryland, held July 2Oth, 1869, it was unanimously resolved that a National Labor Convention be called to meet in the Union League Hall, City of Washington, D.C., on the 1st Monday in December, 1869, at 12 M., to consider:

1st. The Present Status of Colored Labor in the United States and its Relationship to American Industry.

2nd. To adopt such rules and devise such means as will systematically and effectually organize all the departments of said labor, and make it the more productive in its new Political relationship to Capital, and consolidate the Colored Workingmen of the several States, to act in co-operation with our White Fellow-Workingmen in every State and Territory in the Union, who are opposed to Distinction in the Apprenticeship Laws on account of Color, and to so act cooperatively until the necessity for separate organization shall be deemed unnecessary.

3rd. To consider the question of the importation of Contract Coolie Labor, and to petition Congress for the adoption of such Law as will Prevent its being a system of Slavery,

4th. And to adopt such other means as will best advance the interest of the Colored Mechanic, and Workingmen of the whole country.

Fellow-Citizens: You cannot place too great an estimate upon the important objects this Convention is called to consider, viz: your Industrial Interests. In the greater portion of the United States, Colored Men are excluded from the workshops on account of their color.

The laboring man in a large portion of the Southern States, by a systematic understanding prevailing there, is unjustly deprived of the price of his labor, and in localities far removed from the Courts of Justice is forced to endure wrongs and oppression worse than Slavery.

By falsely representing the laborers of the South, certain interested writers and journals are striving to bring Contract Chinese or Coolie Labor into popular favor there, thus forcing American laborers to work at Coolie wages or starve.

The Address of the National Executive Committee, created by the National Convention of Colored Americans, convened in Washington on the 13th of January, 1869, makes a forcible appeal upon this subject. They have and are making noble efforts to overcome these great wrongs, which we feel can only be effectually remedied by the meeting in National Council of the Mechanics and Laborers of this country. We do, as they have, appeal to the white tradesmen and artisans of this country to conquer their prejudices so far as to enable Colored Men to have a fair field for the display of competitive industry; and with this end in view to do away with all pledges, and obligations that forbid the taking of Colored Boys as Apprentice, to trades, or the employment of Colored Journeymen therein.

Delegates will be admitted without regard to race or color. State or City Convention, will be entitled to send one Delegate for each department of Trade or Labor represented in said Convention. Each Mechanical or Labor Organization in every State and Territory is entitled to be represented by one Delegate. It is hoped that all who feel an interest in the welfare and elevation of our race will take an active part in making this Convention a grand success.

By order of the Executive Committee.--William W. Hare, John W. Locks, Wm. L. James, John H. Tabbs, H. C. Hawkins, Geo. Myers, Robert H. Butler, G. W. Perkins, Wm. Wilks, Geo. Grason, Wesley Howard, Daniel Davis, Jos. Thomas.

J. C. FORTIE, Secretary.

ISAAC MYERS, President.

Source: Reprinted in Foner, Philip S., and Ronald L. Lewis, eds. Black Worker: A Documentary History, Volume II: The Black Worker During the Era of the National Labor Union. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1978.

Document 4.10.10

Interview with E.D. Nixon, July 14, 1981

Mr. Nixon posted bail for Rosa Parks after she was arrested for sitting in a “White” seat on a Montgomery bus. He was very active in the bus boycott that followed.

[W]hen I got home, before I got off the train, the superintendent there told me, “I understand you attended the meeting of the Brotherhood yesterday in St. Louis.” I said, “Yes I did.” So he says, “I’ll tell you right now, we’re not going to have any of our porters attending the Brotherhood meeting.” I says, “Well, if somebody told you I attended the meeting there, maybe they told you also that I joined yesterday.” And before he could answer me, I said, “Of course, before I joined I thought about what lawyer I wanted to handle my case if you started to mess with my job. And that’s what I’m going to do—I’m going to drag anybody into court that messes with my job.” And I didn’t even know a lawyer’s name at that time. But I bluffed him out so that he didn’t bother me, and from then on I was a strong supporter of A. Philip Randolph.

Interview with Fred Fair, March 30, 1983

Mr. Fair had served as porter on President Roosevelt’s Pullman car.

When he [Randolph] first started, there wasn’t much organizing you could do, above the boards. You had to sneak around homes and everywhere else and organize. We had men fired. Some of them got back, some of them didn't after the agreement was signed. Everybody didn’t go [along with the union], because they were afraid of losing the job they had, you know, because so many of them had lost their jobs around the country.

Interview with Rosina Tucker, June 19, 1981

I got involved—I could not be involved if my husband was not a porter. You see, this is an organization for the porters, and I became involved as a member of the auxiliary. But before we had an international auxiliary, we had little clubs—like councils, we called them. And in that way all over the country, these councils would help the men to raise money and so forth. And I organized the council here in this very house, very early in the movement, and I was made president.

So, we worked along, my group. We did teas, we did little dances and so forth. And sent it to New York to help them. And other auxiliaries, I suppose, did the same. That’s why I say that the women were the ones who were the backbone, in that they furnished the money and encouragement to the officials. Now, we had a meeting at a certain home once, and the company found out that we had this meeting. So they called the husband in, the porter in, and asked him about it. The porter was able to show by his time sheet that he was out of town. But his wife held the meeting!

The Women’s Auxiliary got started almost the same time as the Brotherhood. We had these small groups of women in every city.

Interview with William Harrington, July 16, 1982

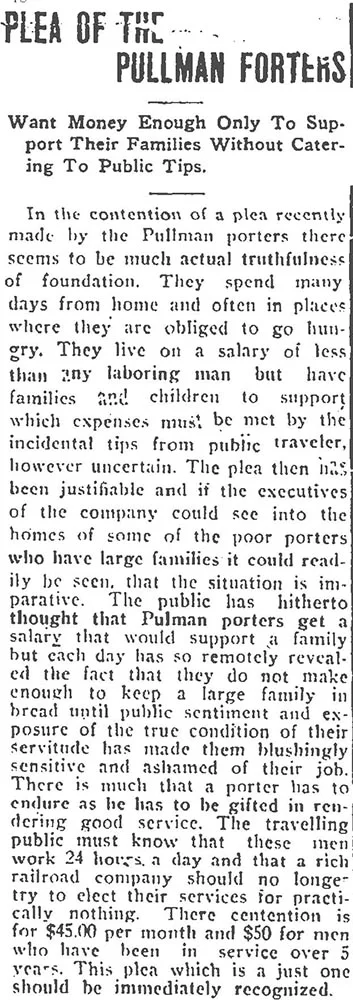

Before 1936, your superintendent would put a yes-man on a run and nobody could bump him. Your seniority was nothing, and that’s the way it was up until 1936. We got the first agreement with the Pullman Company. Of course, we didn’t get that until Franklin D. Roosevelt. When he first came in, he passed a law that we could form a union without interference from your employer. And that’s when you could legally join a union without being fired or being laid off. Of course, the union was formed before that time, but you had to slip to meetings, and it was something like an underground movement, see? Because when the Pullman Company found out you attended a union meeting, you were probably laid off. He tell you to go home until he sent for you. And you may be home a week, or two weeks, but they would punish you, hearing that you attended union meetings.

When that law was passed, it knocked all the stool pigeons out, what we call stool pigeons, that run to the superintendent, carrying news to the superintendent. Some men would cut your throat to make good with the superintendent. In 1927, we were afraid to join. I didn’t join until 1929.

Interview with C.L. Dellums, November 13, 1980

Mr. Dellums was one of the founding members of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters and was fired for his involvement in the union.

We were a handful of Negroes. Had nothing: no money, no experience in this. I used to say that all we had was what God gave the lizard.

We succeeded after twelve long, bitter, expensive years. Somewhere between five hundred and one thousand men were discharged from the Pullman Company as a result of their union activities or their open support of the union. All the money we could take and scrape was put in that struggle. . . .

Source: Santino, Jack. Miles of Smiles, Years of Struggle: Stories of Black Pullman Porters. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1989.

The negotiation of wages, benefits, and working conditions between employers and labor unions on behalf of workers, typically through a formal bargaining process.

An organized association or collective of workers in a particular industry, trade, or profession, formed to protect and promote the interests of its members, negotiate wages and working conditions with employers, and advocate for labor rights, workplace safety, and social justice.

A person employed to carry luggage, goods, or other heavy loads, typically in a commercial or transportation setting such as a railway station, airport, or seaport, and responsible for loading, unloading, and transporting cargo, often using wheeled carts, hand trucks, or other equipment. Porters may work in various industries, including transportation, hospitality, and logistics, and perform physical labor in handling and moving goods or baggage.

A sleeping car, also known as a sleeper, is a railroad passenger car equipped with sleeping accommodations, such as berths or bunk beds, allowing passengers to sleep during overnight journeys.

A period of major economic, technological, and social transformation that began in Britain in the late 18th century and spread to other parts of the world, characterized by the transition from agrarian and handicraft-based economies to industrialized economies based on mechanized manufacturing, urbanization, and the use of steam power and machinery.

A prominent African American labor leader and civil rights activist who organized the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters and was a key figure in the Civil Rights Movement.

A "yellow contract" does not appear to be a widely recognized term. Without further context, its meaning remains unclear.