Unit

Years: 1864-1872

Freedom & Equal Rights

Historical Events, Movements, and Figures

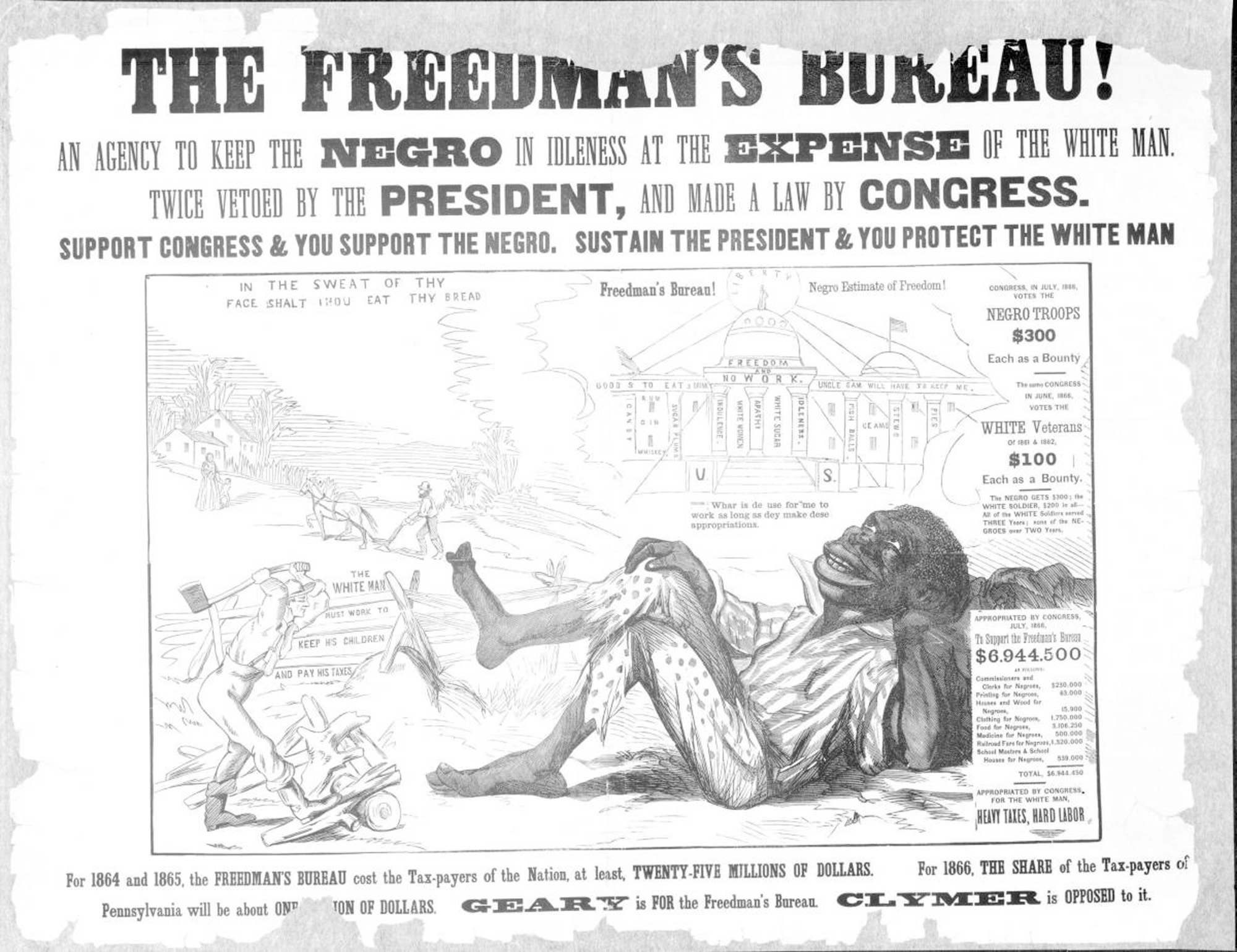

During the Civil War and Reconstruction, the government of the United States intervened in the lives of individual Americans in ways that were unimaginable before the war. They did this for two reasons: to win the war and to ensure a fair and just peace. One of the most revolutionary actions taken by the government during this time was the creation of a new agency called the Freedmen’s Bureau.

Even before the war was won, the federal government recognized the challenge posed by the millions of newly freed African Americans. As Union troops made their way into Confederate territory, enslaved African Americans sought them out, seeking help and offering their services. This created a dilemma for the federal generals and policymakers: What should happen to the territories that the Union army conquered and the people who lived on them?

As the war came to an end, the southern economy was in ruins. Its labor system—slavery—had been abolished. It was widely believed that the freedpeople would struggle to participate effectively in a market economy without proper education. In March 1865, with the war almost over, Congress stepped in to provide government assistance, establishing the Bureau for Freedmen, Refugees, and Abandoned Lands, commonly known as the Freedmen’s Bureau.

The first task of the Freedmen’s Bureau was to provide relief. The war had left many people homeless and destitute. Agricultural production had been disrupted, leaving people close to starvation. Bureau officers spent a significant amount of time distributing food and clothing to displaced southern refugees, White and Black alike. By July 1866, the Bureau had provided over 13 million rations, with most going to African Americans. It also supplied medical care to over half a million patients by 1869.

Another important responsibility of the Bureau was to provide education for the freedpeople. By 1869, the Bureau had helped establish more than 3,000 free public schools with around 150,000 students enrolled. The Bureau often supplied the buildings for these schools, while northern missionary associations provided the teachers. Education became the most enduring legacy of the Freedmen’s Bureau, leading to the establishment of teacher training schools and prominent historically Black colleges such as Fisk, Howard, and Hampton.

The Bureau’s largest role was overseeing the transition from an economy based on slavery to a market economy, in which the freedpeople would participate voluntarily. The Bureau mediated between the freedpeople and their former enslavers, negotiating labor contracts. The Bureau also managed farmland in the South that had been abandoned by owners or destroyed by military forces. These lands were the source of much debate focused on whether they should be distributed to the freedpeople or returned to the White landowners.

The act establishing the Freedmen’s Bureau began life in March of 1864, as a bill in Congress to establish a Bureau of Freedmen in the War Department. Debate in Congress swirled for a year, with a plan for a permanent Bureau scuttled as too radical. Finally, in March of 1865, Congress passed the following act, establishing a temporary agency with a general mandate to aid the freedpeople.

An Act to establish a Bureau for the Relief of Freedmen and Refugees.

Be it enacted . . . That there is hereby established in the War Department, to continue during the present war of rebellion, and for one year thereafter, a bureau of refugees, freedmen, and abandoned lands, to which shall be committed, as hereinafter provided, the supervision and management of all abandoned lands, and the control of all subjects relating to refugees and freedmen from rebel states. . . .

The Secretary of War may direct such issues of provisions, clothing, and fuel, as he may deem needful for the immediate and temporary shelter and supply of destitute and suffering refugees and freedmen and their wives and children, under such rules and regulations as he may direct.

The commissioner, under the direction of the President, shall have authority to set apart, for the use of loyal refugees and freedmen, such tracts of land within the insurrectionary states as shall have been abandoned, or to which the United States shall have acquired title by confiscation or sale, or otherwise, and to every male citizen, whether refugee or freedman, as aforesaid, there shall be assigned not more than forty acres of such land, and the person to whom it was so assigned shall be protected in the use and enjoyment of the land for the term of three years. . . . At the end of said term, or at any time during said term, the occupants of any parcels so assigned may purchase the land and receive such title thereto as the United States can convey, upon paying therefor the value of the land, as ascertained and fixed for the purpose of determining the annual rent aforesaid.

APPROVED, March 3, 1865.

Source: U.S., Statutes at Large, Treaties, and Proclamations of the United States of America, vol. 13 (Boston, 1866), 507-9.

Document 4.9.3: Excerpts from The First Freedman’s Bureau Act, 1865.

General Oliver Otis Howard, head of the Freedmen’s Bureau, sent the following instructions to his Assistant Commissioners in the South during the summer of 1865, just as the war was ending. These regulations directed the work of Bureau agents throughout the South, though there was no guarantee that individual agents would follow them to the letter. Just as important as revealing the intended work of agents, the document illustrates the principles underlying the Bureau’s efforts: racial justice, economic liberalism, and a swift end to government support.

Relief establishments will be discontinued as speedily as the cessation of hostilities and the return of industrial pursuits will permit. Great discrimination will be observed in administering relief, so as to include none that are not absolutely necessitous and destitute. Every effort will be made to render the people self-supporting. Government supplies will only be temporarily issued to enable destitute persons speedily to support themselves. . . .

In all places where there is an interruption of civil war, . . . the control of all subjects relating to refugees and freedmen being committed to this bureau, the Assistant Commissioners will adjudicate . . . all difficulties arising between negroes themselves, or between negroes and whites or Indians. . . .

Negroes must be free to choose their own employers, and be paid for their labor. Agreements should be free, bona fide acts, approved by proper officers, and their inviolability enforced on both parties. The old system of overseers, tending to compulsory unpaid labor and acts of cruelty and oppression is prohibited.

Source: House Ex. Doc., no. 11, 39 Cong., 1 Sess., p. 45. In Walter Fleming, ed. Documentary History of Reconstruction (Cleveland: Arthur H. Clark, 1906), I, 328-30.

Document 4.9.5: Excerpts from “Rules and Regulations for Assistant Commissioners,” 1865

The allocation of funds or resources by a legislative body for specific purposes or programs.

A person from the northern states who went to the southern states after the Civil War to profit from the Reconstruction era, often seen as opportunistic or exploitative.

A person appointed or elected to a position of authority, typically to oversee or regulate a particular area of activity or administration.

Lacking the basic necessities of life, such as food, shelter, and clothing, often as a result of poverty or deprivation.

Individuals who have been forced to flee their home countries due to persecution, war, violence, or natural disasters, seeking refuge and protection in other countries. They are often unable or unwilling to return to their countries of origin due to fear of persecution or violence.

Assistance, support, or aid provided to individuals, communities, or populations affected by disasters, emergencies, poverty, or hardship, aimed at addressing immediate needs and promoting recovery and resilience.

Relating to or characteristic of paternalism, a social or political system characterized by the exercise of authority, control, or guidance by a paternal figure or authority figure, often in a benevolent or authoritarian manner, and involving the imposition of rules, regulations, or restrictions for the supposed benefit or protection of those considered subordinate or dependent. Paternalistic attitudes or policies may involve acts of protection, supervision, or interference perceived as intrusive or authoritarian by those affected.