Unit

Years: 1955-1975

Culture & Community

Historical Events, Movements, and Figures

Prior to this lesson, it would be helpful for students to have a background in the key actions and events of the civil rights movement, especially the nonviolent strategy of civil rights, before beginning this lesson.

You may want to consider prior to teaching this lesson: Many Roads to Freedom

Women comprised the heart and soul of the Civil Rights Movement. Their roles as community organizers, planning and carrying out boycotts and protests on both the national and local level, were indispensable to its success. However, the civil rights movement was not immune to sexism in the broader American culture, and patriarchal values prevented many women from playing more visible roles in the fight for racial justice.

Introduction

Black women played a major role in the civil rights movement. Despite being overlooked by historians for many years, women such as Ella Baker, Fannie Lou Hamer, and Septima Clark not only participated in and supported the efforts of prominent male-led organizations, but were leaders in their own right, especially at the local level. According to Stokely Carmichael, a leader of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and–later–the Black Panther Party, “the ones who came out first for the Movement were the women. If you follow the mass meetings, not the stuff on TV, you’d find women out there giving all the direction. As a matter of fact, we used to say, ‘Once you got the women, the men got to come’” (quoted by Olson p. 15).

Black Women as Political Organizers

Black women were active in local political organizations across the South. According to historian Charles Payne, Black women in the rural South were in fact more politically active than men, particularly in the Mississippi Delta area. Women did more than take civil rights workers into their homes, feeding and providing them with a place to sleep; they also “canvassed more than men, showed up more frequently at mass meetings and demonstrations and more frequently attempted to register to vote” (Payne p. 266). Black women were also political organizers behind the scenes in major protests such as the Montgomery bus boycott, which was organized, planned, and carried out by Black women.

The Black church was an important incubator for Black women leaders during the civil rights movement. Many of the movement’s organizations stemmed from religious organizations, and because women were historically more active in southern churches than men were, they were thus more inclined to join the movement. Involvement through the church became a catalyst for even greater participation from women, as in most southern communities, Black women were connected by a network of social activities ranging from the church to political and social organizations. Thus, when one woman joined a civil rights protest, she was in a good position to communicate her cause to others. Therefore, when it came time to get something done, women were in a better position to disseminate information, or to organize and communicate information to large numbers of people. “It was women going door to door, speaking with their neighbors, meeting in voter registration classes together, organizing through their churches that gave the vital momentum and energy to the movement, that made it a mass movement,” said Andrew Young of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (King p. 469-70).

The Montgomery Bus Boycott and Beyond

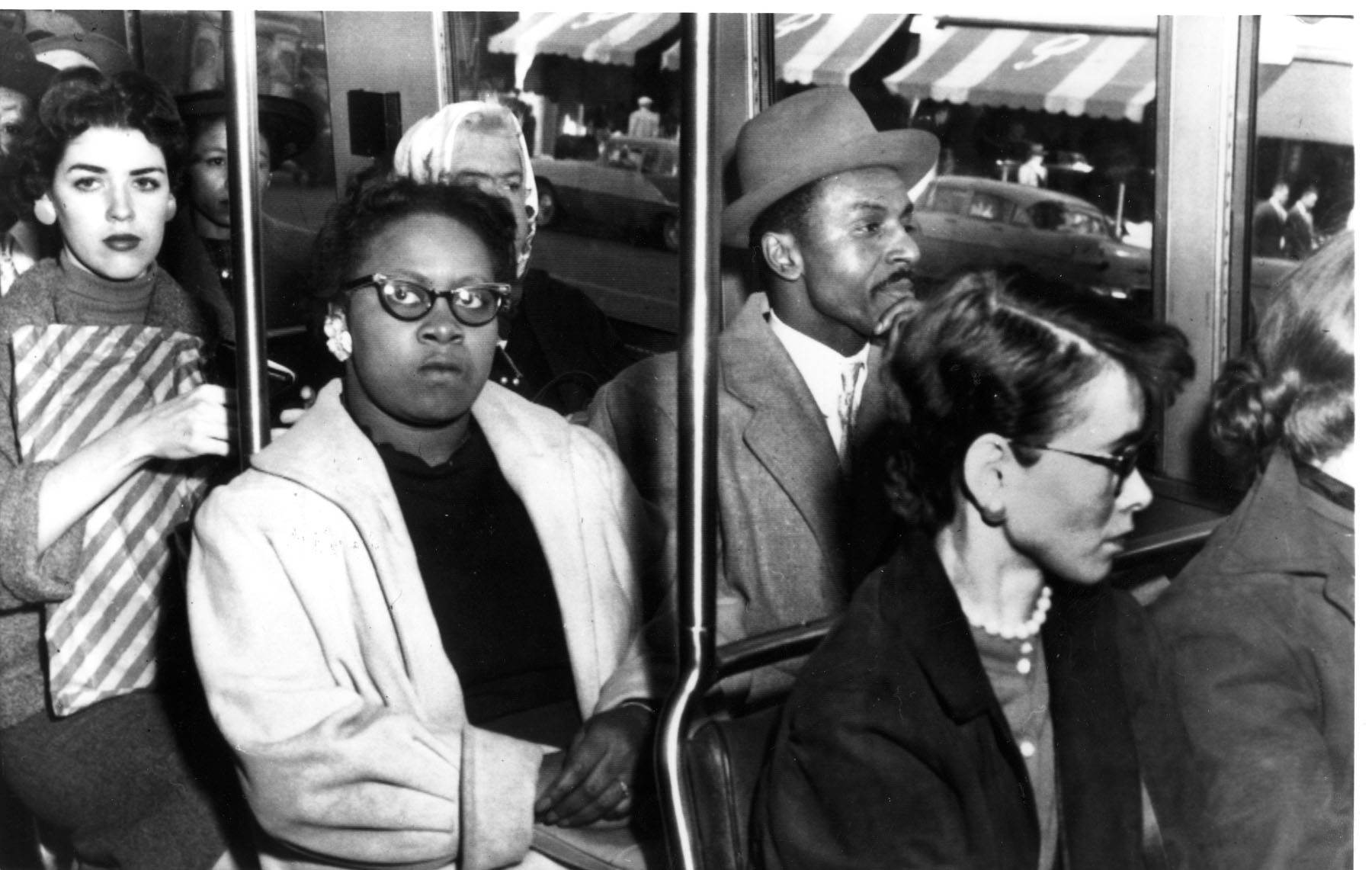

Rosa Parks is one of the best known Black women in American history. While her contribution was significant, the focus on her role tends to obscure the contributions of other African American women. Famous for her role in launching the Montgomery bus boycott of 1955, Parks was merely the catalyst. She did not act alone, nor was she the first to protest segregated buses. In fact, the Montgomery bus boycott had been carefully planned for years by the Montgomery Women’s Political Council (WPC), led by Jo Ann Robinson. Robinson, an English professor, had experience with the degradation of being forced to ride in the back of city buses. In 1949, Robinson and the WPC complained to bus officials, but no changes were made. In 1955, the fed-up WPC developed plans for a citywide bus boycott and waited for the opportune moment to launch their campaign. When police arrested Parks for refusing to give up her seat to a White man, the WPC jumped into action, starting a boycott that lasted 381 days. Ultimately, the U.S. Supreme Court weighed in on the issue of segregated seats on public buses, ruling in November 1956 that the practice was unconstitutional and giving the civil rights movement an early victory.

Women’s involvement did not stop there, and many women held prominent leadership roles in advocating for Black communities through both the nonviolent approach to civil rights as well as the Black power movement. In the nonviolent movement, Diane Nash organized sit-ins in Nashville and was a mainstay during the Freedom Rides; Septima Clark’s work on voter registration drives and Black education earned her the nickname of “the mother of the movement”; Fannie Lou Hamer testified in front of Congress about the injustice of Jim Crow voter restrictions; and Ella Baker was a founder of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. When the Black power movement gained momentum in the late 1960s, women were at the forefront there, too: Tarika Lewis was the first woman to join the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense and quickly became one of their most prolific graphic artists; Ericka Huggins, Kathleen Cleaver, and Elaine Brown led the New Haven chapter of the Black Panthers; and Angela Davis continues to advocate and speak up for Black power and intersectional racial justice in her work as a speaker, writing, and professor. And these are just a few of the women in the epicenter of the civil rights movement–many, many more participated.

Gender in the Civil Rights Movement

Although women had a significant and tangible effect on the civil rights movement’s most successful campaigns, their contributions were often overshadowed by the more visible male leadership of the movement, and sexism often stunted women leaders rising in the ranks. For instance, the March on Washington–the action where Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech–did not feature any women speakers, and the march’s leadership sent an all-male delegation to meet with policy-makers after the march. People like Pauli Murray who did not fit into the gender binary were further marginalized and forgotten, despite having a meaningful impact on the movement. It should come as no surprise that the organizations leading the civil rights movement replicated the patriarchal culture that permeated every aspect of American society (intentionally or not). Though a new Black feminism emerged out of the changing gender roles of the Black power movement, it would take decades for a truly intersectional approach to racial justice to take hold.

Atwater, Deborah F. “Editorial: The Voices of African American Women in the Civil Rights Movement.” Journal of Black Studies, vol. 26, no. 5, 1996, pp. 539–42. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/2784881. Accessed 11 July 2023.

Barnett, Bernice McNair. “Invisible Southern Black Women Leaders in the Civil Rights Movement: The Triple Constraints of Gender, Race, and Class.” Gender and Society, vol. 7, no. 2, 1993, pp. 162–82. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/189576. Accessed 11 July 2023.

Berry, Daina Ramey, and Kali Nicole Gross. A Black Women’s History of the United States. Boston: Beacon Press, 2020.

Brooks Higginbotham, Evelyn. “Beyond the Sounds of Silence: Afro-American Women in History.” Gender and History. Spring 1989.

Crawford, Vicki L., Jacqueline Anne Rouse, and Barbara Woods, Editors. Women in the Civil Rights Movement: Trailblazers and Torchbearers, 1941-1965. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1993.

Drury, Doreen M. “Boy-Girl, Imp, Priest: Pauli Murray and the Limits of Identity.” Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion, vol. 29, no. 1, 2013, pp. 142–47. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2979/jfemistudreli.29.1.142. Accessed 11 July 2023.

Gilkes, Cheryl Townsend. If It Weren’t for the Women: Black Women’s Experience and Womanist Culture in Church and Community. Maryknoll, New York: Orbis Books, 2001.

Hine, Darlene Clark, Wilma King, and Linda Reed, Editors. We Specialize in the Wholly Impossible: A Reader in Black Women’s History. Brooklyn, New York: Carlson Publishing Company, 1995.

Holladay, Jennifer. “Sexism in the Civil Rights Movement: A Discussion Guide.” Learning For Justice, July 7, 2009, https://www.learningforjustice.org/magazine/sexism-in-the-civil-rights-movement-a-discussion-guide

Langston, Donna. “Black Civil Rights, Feminism and Power.” Race, Gender & Class, vol. 5, no. 2, 1998, pp. 158–66. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41675328. Accessed 11 July 2023.

Mills, Kay. This Little Light of Mine: The Life of Fannie Lou Hamer. New York: Dutton Press, 1993.

Nadasen, Premilla. “Black Power, Gender, and Transformational Politics.” Journal of Civil and Human Rights, vol. 1, no. 2, 2015, pp. 236–40. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.5406/jcivihumarigh.1.2.0236. Accessed 11 July 2023.

Nelson, Stanley, and Laurens Grant. The Black Panthers: Vanguard of the Revolution Widescreen ed., PBS Distribution, 2016.

Peppard, Christiana Z. “Poetry, Ethics, and the Legacy of Pauli Murray.” Journal of the Society of Christian Ethics, vol. 30, no. 1, 2010, pp. 21–43. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/23562860. Accessed 11 July 2023.

Robinson, Jo Ann. The Montgomery Bus Boycott and the Women Who Started It: The Memoir of Jo Ann Robinson. Knoxville, TN: University of Tennessee Press, 1987.

Weber, Shirley N. “Black Power in the 1960s: A Study of Its Impact on Women’s Liberation.” Journal of Black Studies, vol. 11, no. 4, 1981, pp. 483–97. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/2784076. Accessed 11 July 2023.

Williams, Rhonda Y. “Black Women and Black Power.” OAH Magazine of History, vol. 22, no. 3, 2008, pp. 22–26. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/25162182. Accessed 11 July 2023.

“Women in the Civil Rights Movement.” Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/collections/civil-rights-history-project/articles-and-essays/women-in-the-civil-rights-movement/

While it may be tempting for students to harshly judge the male leaders of the civil rights movement for their exclusion of Black women, this lesson offers an opportunity for students to practice the critical thinking skill of holding two truths at once: that the men at the forefront of the movement had heroic traits and led heroic actions, and that they also replicated sexism within the movement. We encourage teachers to model and hold space for such critical analysis of the role of gender in the movement. Introducing students to the concept of intersectionality through the work of Kimberlé Crenshaw may also aid in this work.

Any discussion of gender roles also necessitates a definition of gender as a social construct and a deep examination and interrogation of the gender binary. While this lesson focuses primarily on women, there are opportunities to discuss the roles of trans, nonbinary, and other queer and gender expansive activists to the civil rights movement. We recommend taking care to clarify for students that gender expansive people did participate in meaningful ways and to contextualize the historical context for this lesson, as people used different language for gender and sexuality than we do today. Those who did not fit neatly into the gender binary were further marginalized, as demonstrated by the life of Pauli Murray, and this fact may underscore the essential understanding about sexism in the civil rights movement.

We recommend having a conversation with students about the ways in which the language we use about race has changed since this time. Many primary documents of the time period contain references to “negro” or “negroes”. It is important to clarify that students should be mindful with language that they use to discuss the past, when terms differ from what is most appropriate to use today.

Finally, some of the activities incorporate an introduction to and activities around intersectionality. Intersectionality refers to the interconnections between social and demographic categories of identity such as race, gender, and class and how these different categories can connect to create unique experiences of discrimination and disadvantage. Teaching about intersectionality includes ensuring that students understand and connect with the concepts of identities and understand how social structures impact each differently. You can learn more on teaching and developing this skill further using materials such as Learning for Justice’s Toolkit for “Teaching at the Intersections”.

Black women played a major role in the civil rights movement. Despite being overlooked by historians for many years, women were very active in local political organizations across the South. Black women like Septima Clark, Fannie Lou Hamer, and Ella Baker were at the forefront of voter registration drives, educational campaigns, and even massive actions like the Montgomery Bus Boycott, which was completely woman-organized and woman-led. “It was women going door to door, speaking with their neighbors, meeting in voter registration classes together, organizing through their churches that gave the vital momentum and energy to the movement, that made it a mass movement,” said Andrew Young of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. And Black women were also vital to the Black power movement that emerged as the 1960s raged on, contributing artwork and organizing power to organizations like the Black Panther Party.

So why, then, were the important contributions of women eclipsed by men both during the movement and after, in history’s retelling of it? Why did the March on Washington feature an all-male panel of speakers, and why were women absent from most meetings between politicians and civil rights leaders? The civil rights movement was not immune to the sexism plaguing American culture more broadly, and the forces keeping women behind the scenes in the United States were also active within the ranks of the movement for civil rights, as well as within history. It is only within recent years that historians have begun to analyze the role that gender played within the civil rights movement and to uncover the many inspiring Black women who contributed to the fight for racial justice in the United States.

Select the activities and sources you would like to include in the student view and click “Launch Student View.”

It is highly recommended that you review the Teaching Tips and sources before selecting the activities to best meet the needs and readiness of your students. Activities may utilize resources or primary sources that contain historical expressions of racism, outdated language or racial slurs.

In order to engage in a Carousel Conversation, place students into pairs, and assign each pair one of the following women, with consideration of your student in relation to gather materials through internet searches or assigned reading choices, who contributed to the civil rights and/or Black power movements:

Instruct each pair to research their assigned person using the internet/provided readings and any primary or secondary sources from class. They should respond to selected questions about their person:

Then sit students in two rows facing each other for the “speed dating” activity. Students will share about their assigned historical figure with the partner sitting across from them. Time each round at 2-3 minutes, and have one row move down a seat between rounds so that each student has a new partner for each new round.

After several rounds, lead a class discussion to debrief the activity using the following questions:

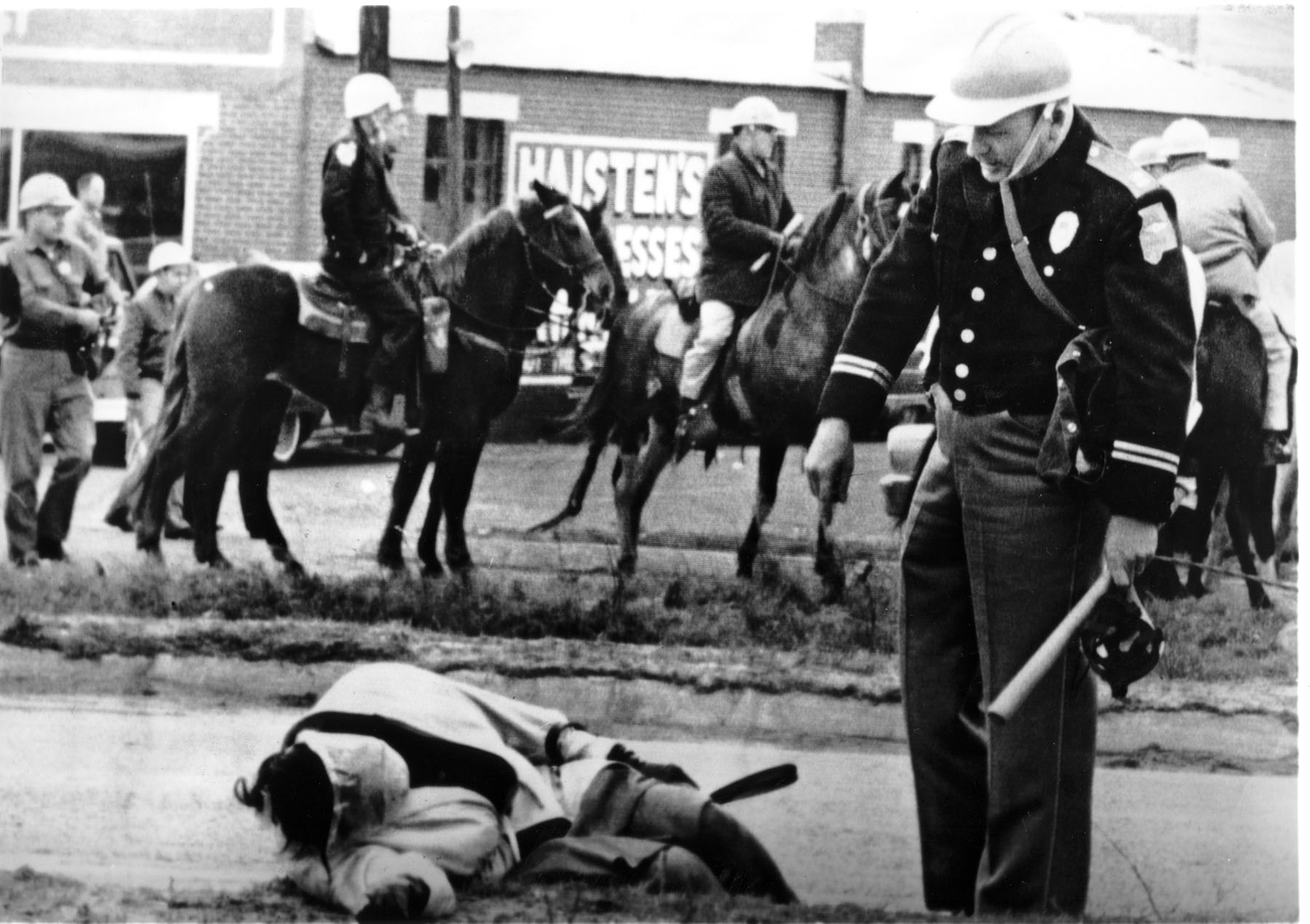

Place students into small groups of 3-4. Distribute one of the following selected photographs to each group.

As a group, have students answer the following questions about their photo:

Have a representative from each group share their answers with the full class. Then, have students write a 1-paragraph reflection in response to the following prompt:

Have students use the internet to research a definition of intersectionality, a theory and term coined by the scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw. Share out definitions and write a class definition on the board.

Then, have students individually research the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP). Each student should list 5-10 facts about the MFDP and share them with the class. Distribute copies of Fannie Lou Hamer’s 1964 testimony to the Democratic National Convention on behalf of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party. Allow time for students to read the document individually. Give a content warning, as this document contains graphic details of racial violence as well as the n-word.

Then place students into groups of 2-3 students each. The groups should each use the OPCVL protocol to analyze the document.

Then, share out as a full class. Facilitate a debrief discussion using the following questions:

For this Socratic Seminar, have students read Pauli Murray’s 1963 speech titled “The Negro Woman in the Quest for Equality.” It may be helpful for this text to have students do some background research on Pauli Murray, who was a Black activist that scholars now think may have been trans and/or nonbinary. Because those labels did not yet exist in the 1960s, Murray used she/her pronouns at the time, but some scholars use they/them for Murray today. To extend this activity, consider having a conversation with students about the complexities of an intersectional identity in connection with the documentary “My Name is Pauli Murray.”

After the seminar, lead a reflection in which students answer the following questions:

In groups of 3-4, have students review the source “Panther Sisters on Women’s Liberation”–both the interview and the visual cartoon.

The group should discuss the following questions together:

Then, have each group create a political cartoon contrasting the roles of women in the nonviolent civil rights movement and the Black power movement. Allow each group to share their cartoons with the class.

Explain to students that women’s changing roles during the Black power movement led to the creation of an intersectional Black feminism in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Place students into small groups and assign each small group one of the following founders or groups of early Black feminism.

Each group should research their assigned person or group and create a poster to teach the class about their contributions and ideas. Once all groups have finished their posters, lead a gallery walk where students take notes on the other posters to learn about all the Black feminist leaders and groups. Finally, facilitate a conversation with the full class using the following discussion prompts:

Have each individual student select a woman from the civil rights or Black power movement that they feel should be inducted into the “Women’s Hall of Fame.” Guide students in writing a research question, locating scholarly and primary sources, and taking notes on their sources. Once students have gathered enough information to answer their research questions, instruct them to write a speech about their chosen changemaker that they will present at the Hall of Fame Induction Ceremony. Hold the ceremony during class as a way for students to deliver their speeches to an authentic audience, and consider inviting school leadership.

After the Hall of Fame Induction Ceremony, have students reflect on the following questions, either in a class discussion or a written reflection:

Please login or sign up to access the student view functions.