Unit

Years: 1919-1925

Historical Events, Movements, and Figures

Prior to this lesson, students should be familiar with the African diaspora – particularly the history of Black people in the West Indies, and the immigration of peoples from the West Indies to the United States, especially New York City. Students should have an understanding of the racial climate of the United States in 1919, inclusive of the racism and violence that greeted Black soldiers as they returned home from fighting in World War I, and the extreme violence of White Supremacist organizations such as the Klu Klux Klan in the American South.

You may want to consider prior to teaching this lesson: Moving North Plessy v. Ferguson The Breakdown of Justice: Lynching and the Scottsboro Case

Marcus Garvey inspired people with his convictions about Black unity, pride, and economic independence in the early 20th century. As leader of the largest Black international organization in history, the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA), he had the opportunity to make his voice and beliefs known. Garvey and the UNIA were propelled to the forefront of Black activism in the 1920s, when their message resonated powerfully with working-class Black men and women. Despite his popularity, Garvey faced opposition in the United States from other well known Black leaders as well as the United States government. Garvey’s work also involved failures, missteps and financial setbacks, complicating his reputation. His most important legacy was his inspiration to worldwide Black nationalist leaders and intellectuals who followed him.

Marcus Garvey, charismatic leader and early promoter of Black nationalism and racial pride, galvanized Black working-class men and women throughout the African diaspora in the early 20th century. Born in Jamaica in 1887, Garvey rose to prominence by building an enormous base of power and popularity in Harlem, New York during the 1920s. The organization that expressed his vision, the Universal Negro Improvement Association, became one of the largest Black social change movements in history. Garvey’s career involved failures, missteps and financial mismanagement as well as successes, complicating his reputation. Ultimately, his most important legacies were his visionary ideas and their inspiration to numerous Black nationalist leaders, artists, and intellectuals who followed him.

Marcus Garvey, Early Life and Work

Marcus Garvey was born in St. Ann’s Bay, Jamaica, to a working family of modest means, and left formal schooling at the age of 14. Garvey worked as a printer, journalist, and labor organizer in Jamaica, then Central America and Britain. In 1914, back in Jamaica, Garvey established the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) alongside Amy Ashwood– soon to be his first wife. Two years later, believing Jamaica was too small and the people unreceptive to the message, they moved to the United States. Garvey set up headquarters for his international organization in Harlem, New York City. The Association’s emphasis on black pride and economic self-sufficiency resonated with African Americans frustrated and disillusioned by decades of segregation. His message spoke most powerfully to non-elite Black men and women, the working class masses of Black urban communities. The UNIA held vibrant and participatory conventions and parades, where Garvey often dressed in military or academic clothing.

Garvey’s Vision

Garvey’s philosophies on race and race relations, promoted by the UNIA, can be summarized in six points. First, he believed that Blacks and Whites could not be truly integrated, and that Black people would never be able to succeed while playing by white rules. Second, he believed that Blacks should not intermarry but remain a pure race. Third, that Black people should create their own economic system, that is, their own factories and businesses. In fact, the organization itself created many Black-owned and operated businesses, including their famous, yet short-lived, Black Star Line fleet of cruise ships. Fourth, that they should be proud of their African heritage and race. Fifth, that all Black nations, especially those in Africa, must be given back to their Black majority populations; white European colonization should be eradicated. And sixth, Garvey held that some North American, Central and South American, and Caribbean Black people should move back to Africa and form and lead an African nation.

Key Initiatives

The UNIA went by the slogan, “One God! One Aim! One Destiny!” and achieved remarkable success as the first and largest international Black organization. At its height in the early 192os, the association had galvanized millions of followers worldwide. It is important to note that Garvey’s beliefs would later develop into the Black Nationalism movement of the 1950s and ‘60s, led, in part, by Malcolm X– whose father was a UNIA organizer in Michigan.

The UNIA also differed from many organizations of its era as women held many leadership positions. Three of the six directors in 1918 were female, and each local division had both a Lady President and Male President. Though these roles differed by region in terms of power distribution, women resisted marginalization throughout the history of the UNIA– a topic long overlooked in historical accounts of the movement.

Obstacles and Opposition

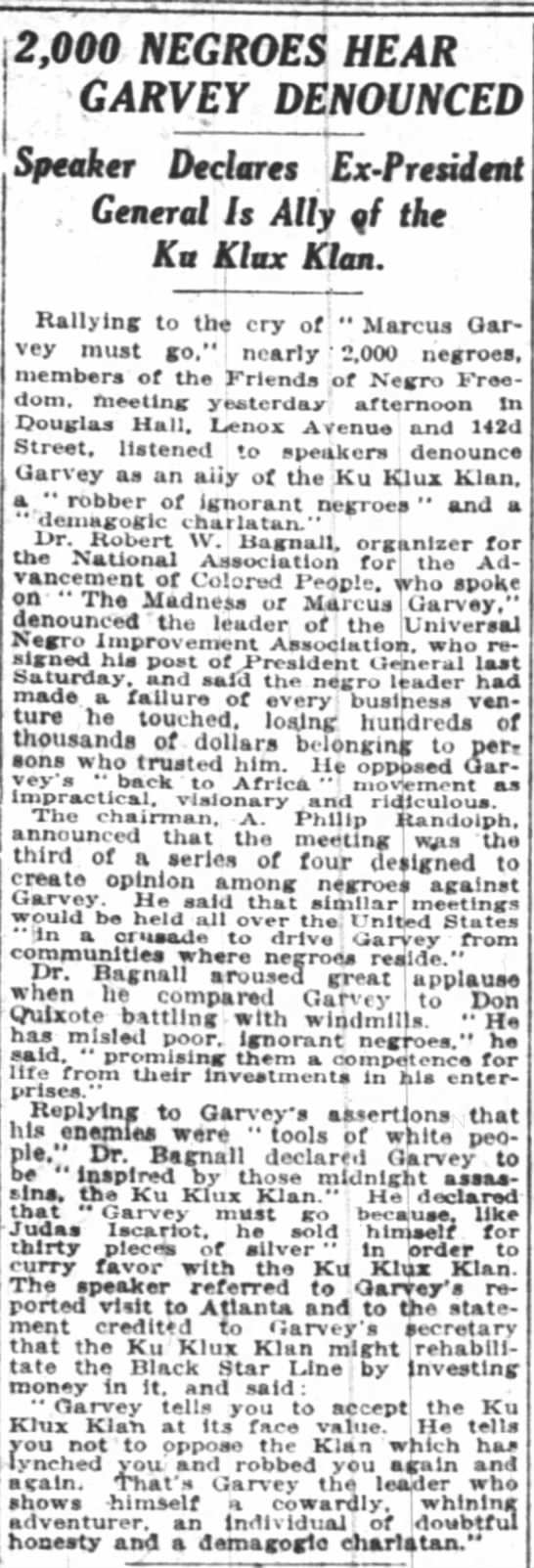

Garvey’s ideas and actions were not without critics. Many observers and rivals, Black and White, regarded his self-presentation and over-the-top parades and conventions as worthy of ridicule. Many also disagreed with Garvey’s notions of a segregated, Black “pure race,” as well as his ties with racist white groups, such as his meeting in 1925 with acting Imperial Wizard Edward Young Clark of the Ku Klux Klan. Of the KKK, he said, “They are better friends to my race, for telling us what they are, and what they mean, thereby giving us a chance to stir for ourselves. . . . Every white man is a Klansman. . . . and there is no use lying about it.”

Recent scholarship has also identified the role of Colorism– skin-color privilege and bias– in Garvey’s tense rivalries with elite and educated Black leaders in the U.S. and the Caribbean. The influential African American leader, W. E. B. DuBois and some of his peers were highly dismissive. DuBois described Garvey as, “The most dangerous enemy of the Negro race in America and the world.” A. Philip Randolph’s newspaper, Messenger, referred to Garvey as “ an unquestioned fool and ignoramus.”

Due in part to Garvey’s poor business practices, his ventures went bankrupt, and he was briefly jailed for illegal business practices (although it is not known whether he was, in fact, set up by his opponents). The U.S. government deported Garvey back to Jamaica in 1927. He never returned to the United States. At the age of fifty-two, Marcus Garvey suffered a stroke and died.

A Long-Lasting Legacy

Garvey represented something profound to many Black people. He was a visionary who rose from being a worker to leader of a historically groundbreaking mass movement. Garvey changed the way many Black people saw themselves—and the world.

Garvey’s vision inspired many of the revolutionaries who fought for African Independence in the 1950’s and 1960’s. This included Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana, who later realized Garvey’s dream of the Black Star Line in creating the state shipping corporation of Ghana; the black star also stands at the center of Ghana’s flag and gave its name to the Ghanaian football team.

Garvey is a figure of intense national pride in Jamaica and regarded as a prophet in the Rastafarian religion. His words and work are fundamental to reggae as seen in the work of artists from Bob Marley, Peter Tosh and Burning Spear to Damian Marley and Nas (Swan 2017). In the United States, Garvey’s message seeded the Black Power and Black is Beautiful movements. The Pan African flag designed by Garvey continues to rally Black pride and be a symbol of Black power. Thus, despite his opposition, obstacles, and missteps, Marcus Garvey’s vision of a proud, unified, and self-reliant Black people lives on.

Marcus Garvey: Pan-Africanist (Throughline 2021)(Podcast)

Marcus Garvey and the Universal Negro Improvement Association (David Van Leeuwen, ©National Humanities Center)

MARCUS GARVEY AND THE UNIA – Myseum of Toronto

Universal Negro Improvement Association (PBS)

Marcus Garvey: Look for me in the Whirlwind Resources (PBS)

Colorism (Kendi); Stamped From the Beginning – Chapter 25 (Kendi)

The Marcus Garvey and Universal Negro Improvement Association Papers Project Copyright © 1995-2014 The Marcus Garvey and UNIA Papers Project, UCLA

Photo Gallery (UCLA)

“Philosophy and Opinions of Marcus Garvey” by Marcus Garvey, Edited by Amy Jacques-Garvey is in the Public Domain

A History Of Beef Between Black Writers, Artists, and Intellectuals (Codeswitch)

Marcus Garvey, like all leaders, was a complex figure who had flaws and made mistakes. As students learn about his failures and success, support them in examining the complexities of the different interpretations of Garvey based on the varying identities and needs of his audiences.

Colorism underlies the tension between W.E.B. DuBois and Marcus Garvey. (Teachers can access Ibram Kendi’s short essay, “Colorism as Racism: Garvey, Du Bois and the Other Color Line” to build their own background knowledge.) Colorism is the systemic and ideological skin color privilege granted to light-skinned bodies and the belief that lighter skin somehow signifies more worth, virtue, or capability. As you discuss Colorism it is important to recognize that it continues to exist and this may be or may become a controversial topic in your classroom. Help students use inquiry-based perspective taking – particularly reserving judgment on historical figures, asking questions instead of jumping to assumptions, and being mindful of the language they use and assumptions they make about the ideas and experiences of figures in the past and their peers in the present.

The secondary sources in this lesson use the term Black to refer to all members of the African diaspora, not simply African Americans. It is important in Garvey’s case to consider both his Jamaican ancestry and his connection to Africa. We recommend having a conversation with students about the different terms that may appear in the sources as well as the ways in which the language we use about race has changed since this time. Many primary documents of the time period also contain references to “negro” or “negroes”. It is important to clarify that students should be mindful with language that they use to discuss the past, when terms differ from what is most appropriate to use today. You may find the Racial and Ethnic Identity guide from APA to be a helpful tool for your own reference when introducing different terms.

Finally, when sharing the Student Context essay you should be aware that it includes a reference to lynching. Lynching is an extremely violent and traumatic reality of Black history in the United States and should also be presented from a trauma-informed lens. It is imperative that teachers are sensitive to the emotional reactions of their students when discussing details of lynchings. Recent scholarship refers to lynching as racial terrorism, and we recommend that teachers adopt this language to make it clear to students the extent to which lynching brutalized and traumatized Black communities. You can learn more to support your scholarship in this area (i.e., the Red Summer and lynching) through this National Archives resource which outlines that during this time lynchings proliferated and “thousands of African Americans were hanged, burned to death, shot to death, tortured, mutilated, and castrated by white mobs who almost never were prosecuted for their crimes.”

Marcus Garvey was born in Jamaica in 1887. Jamaica is an island nation in the West Indies. Though slavery was abolished there in 1864, Jamaica was a colony of the United Kingdom until 1962. Marcus Garvey, along with fellow Jamaican Amy Ashwood, founded the Universal Negro Improvement Association (or UNIA) in Jamaica in 1914. The aim of the organization was to preach Black nationhood and identity through economic independence and connection to a shared African history and culture. Garvey challenged people to look at the true history and wealth of the African continent with pride.

In 1916, Garvey and Ashwood moved to the United States, where their message of economic self-reliance, proud Black identity, and community solidarity resonated powerfully for many working-class Black men and women.This was particularly true in light of the institutional and direct racism of that time which included:

Garvey and Ashwood founded a New York branch of the UNIA, began the Negro World newspaper and created a steamship company called The Black Star Line. Garvey quickly became a rising leader with his insistence that Black economic and political independence were possible for all Black people throughout the diaspora. He inspired people with his conviction in Black unity, pride, and autonomy. As a result, Garvey and the UNIA were propelled to the forefront of Black activism. By 1920, there were a thousand UNIA branches throughout the Americas and Africa.

Despite his popularity and financial endeavors, Garvey faced a tremendous amount of opposition in the United States both from other well known leaders such as W.E.B. DuBois and from the United States government. Garvey’s work also had failures, missteps and financial setbacks. Despite these controversial aspects of his career, Garvey’s ideas were inspiring for many Black nationalists that followed. These included 1960s leaders of the newly independent African nations such as Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana, and in the US, Malcolm X’s writings, and the Black Power movement of the 1960s. Artists and musicians have also found inspiration in Garvey, from Bob Marley, Peter Tosh and Burning Spear to Damian Marley and Nas. These influences are his most enduring legacy.

Select the activities and sources you would like to include in the student view and click “Launch Student View.”

It is highly recommended that you review the Teaching Tips and sources before selecting the activities to best meet the needs and readiness of your students. Activities may utilize resources or primary sources that contain historical expressions of racism, outdated language or racial slurs.

Prior to the start of the Silent Discussion, select the primary sources and discussion question(s) below that best match your aim for this lesson, in order to learn about and understand the lasting legacy of Marcus Garvey on different audiences.

Introduce students to the term Pan-Africanism and then begin by having students read the student context if they have not already done so. Then, introduce that by 1920 Marcus Garvey had a huge audience. Garvey’s nightly meetings in Liberty Hall had regular audiences of six thousand. His newspaper, Negro World, had a circulation of between 50,000 and 200,000. Garvey claimed that the United Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) had six million members and while it’s hard to know if that is true, there were certainly many people worldwide who believed in his message.

Discussion Questions:

Instruct students to write a paragraph response to the discussion prompt, and then leave their response on their desk as you begin the discussion.

After the Silent Discussion, have students reflect as a whole class or in small groups on the following:

“I asked, ‘Where is the black man's Government?’ ‘Where is his King and his kingdom?’ ‘Where is his President, his country, and his ambassador, his army, his navy, his men of big affairs?’ I could not find them, and then I declared, ‘I will help to make them.’”

"The Negro's Greatest Enemy," published in Current History (18:6, September 1923), written in the Tombs Prison in New York City.

“The Dream of a Negro Empire

. . . What we want is an independent African nationality. . . It is hoped that when the time comes for American and West Indian Negroes to settle in Africa, they will realize their responsibility and their duty. . . it shall be the purpose of the Universal Negro Improvement Association to have established in Africa the brotherly co-operation which will make the interest of the African native and the American and West Indies Negro one and the same, that is to say, we shall enter into a common partnership to build up Africa in the interest of our race.”

Excerpt from the Negro World, Vol. XII, No. 10? New York, Saturday, April 22, 1922

Written by Marcus Garvey, President General, Universal Negro Improvement Association, New York, April 18, 1922

Document 5.6.2: Excerpts from “The Future as I See It,” Marcus Garvey, 1923.

The Negro is Ready

We are organized for the absolute purpose of bettering our condition, industrially, commercially, socially, religiously and politically. We are organized not to hate other men, but to lift ourselves, and demand respect of all humanity, We have a program that we believe to be righteous; we believe it to be just, and we have made up out minds to lay down ourselves on the altar of sacrifice for the realization of this great hope of ours, based upon the foundation of righteousness. We declare to the world that Africa must be free, that the entire Negro race must be emancipated from industrial bondage, peonage and serfdom; we make no compromise, we make to apology in this our declaration. We do not desire to create offense on the part of other races, but we are determined that we shall be heard, that we shall be given the rights to which we are entitled….

Deceiving the People

There is many a leader of our race who tells us that everything is well and that all things will work out themselves and that a better day is coming. Yes, all of us know that a better day is coming; we all know that one day we will go home to Paradise, but whilst we are hoping by our Christian virtues to have an enter into Paradise we also realize that we are living on earth an that the things that are practiced in Paradise are not practiced here. You have to treat this world as the world treats you; we are living in a temporal, material age, an age of activity, and age of racial, national selfishness. What else can you expect but to give back to the world what the world gives to you, and we are calling upon the four hundred million Negroes of the world to take a stand, that we shall occupy a firm position; that position shall be an emancipated race and a free nation of our position; that position shall be an emancipated race and a free nation of our own. We are determined that we shall have a free country; we are determined that we shall have a flag we are determined that we shall have a government second to none in the world.

An Eye for an Eye

Men may spurn the idea, they may scoff at it, the metropolitan press of this country may deride us; yes, white men may laugh at the idea of Negroes talking about government; but let me tell you there is going to be a government, and let me say to you also that whatsoever you give, in like measure it shall be returned to you. The world is sinful, and therefore man believes in the doctrine of an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth. Everybody believes that revenge is God’s, but at the same time we are men, and revenge sometimes springs up, even in the most Christian heart.

Why should man write down a history that will react against him? Why should man perpetrate deeds of wickedness upon his brother which will return to him in like measure? Yes, the Germans maltreated the French in the Franco-Prussian war of 1870, but the French got even with the Germans in 1918. It is history, and history will repeat itself. Beat the Negro, brutalize the Negro, kill the Negro, burn the Negro, imprison the Negro, scoff at the Negro, deride the Negro, it may come back to you one of these fine days, because the supreme destiny of man is in the hands of God. God is no respecter of persons, whether that person be white, yellow or black. Today the one race is up, tomorrow it has fallen; today the Negro seems to be the footstool of the other races and nations of the world; tomorrow the Negro may occupy the highest rung of the great human ladder.

But, when we come to consider the history of man, was not the Negro a power, was he not great once? Yes, honest students of history can recall the day when Egypt, Ethiopia and Timbuctoo towered in their civilizations, towered above Europe, towered above Asia. When Europe was inhabited by a race of cannibals, a race of savages, naked men, heathens and pagans, Africa was peoples with a race of cultured black men, who were cultured and refined; men who, it was said, were like the gods. Even the great poets of old sang in beautiful sonnets of the delight it afforded the gods to be in companionship with the Ethiopians. Why, then; should we lose hope? Black men, you were once great; you shall be great again. Lose not courage, lose not faith, go froward. The ting to do is to get organized; keep separated and you will be exploited, you will be robbed, you will be killed. Get organized, and you will compel the world to respect you. If the world fails to give you consideration, because you are black men, because you are Negroes., four hundred millions of you shall, through organization, shale the pillars of the universe and bring down creation, even as Samson brought down the temple upon his head and upon the heads of the Philistines.

An Inspiring Vision

So Negroes, I say, through the Universal Negro Improvement Association, that there is much to live for. I have a vision of the future, and I see before me a picture of a redeemed Africa, with her dotted cities, with her beautiful civilization, with her millions of happy children, going to and fro. Why should I lose hope, why should I give up and take a back place in this age of progress? Remember that you are men, the God created you Lords of this creation. Lift up yourselves, men, rise as high as the very stars themselves. Let no man pull you down, let no man destroy your ambition, because man is but your companion, your equal; man is your brother; he is not your lord; he is not your sovereign master.

We of the Universal Negro Improvement Association feel happy; we are cheerful. Let them connive to destroy us; let them organize to destroy us; we shall fight the more. Ask me personally the cause of my success, and I say opposition; oppose me, and I fight the more, and if you want to find out the sterling worth of the Negro, oppose him, and under the leadership of the Universal Negro Improvement Association he shall fight his way to victory, and in the days to come, and I believe not far distant, Africa shall reflect a splendid demonstration of the worth of the Negro, of the determination of the Negro, to set himself free and to establish a government of his own.

Source: reprinted in Jacques-Garvey, Amy., ed. Philosophy and Opinions of MarcusGarvey: Volumes I and II. New York: Antheneum, 1923. Reprinted in 1969

“The Universal Negro Improvement Association appeals to each and every Negro to throw in his lot with those of us who, through organization, are working for the universal emancipation of our race and the redemption of our common country, Africa. No Negro, let him be American, European, West Indian or African, shall be truly respected until the race as a whole has emancipated itself, through self—achievement and progress, from universal prejudice. The Negro will have to build his own government, industry, art, science, literature and culture, before the world will stop to consider him.”

Excerpt from “An Appeal to the Conscience of the Black Race to See Itself” by Marcus Garvey, 1923

For this Socratic Seminar, have students read the Declaration of the Rights of the Negro Peoples of the World to discuss Marcus Garvey’s vision and its impact on members of the African Diaspora over the past century. Questions that may prompt initial discussion:

After the seminar, lead a reflection in which students answer the following question:

“Declaration of the Rights of the Negro Peoples of the World”: The Principles of the Universal Negro Improvement Association

Preamble-Be It Resolved, That the Negro people of the world, through their chosen representatives in convention assembled in Liberty Hall, in the City of New York and United States of America, from August 1 to August 31, in the year of Our Lord one thousand nine hundred and twenty, protest against the wrongs and injustices they are suffering at the hands of their white brethren, and state what they deem their fair and just rights, as well as the treatment they propose to demand of all men in the future.

We complain:

1. That nowhere in the world, with few exceptions, are black men accorded equal treatment with white men, although in the same situation and circumstances, but, on the contrary, are discriminated against and denied the common rights due to human beings for no other reason than their race and color.

We are not willingly accepted as guests in the public hotels and inns of the world for no other reason than our race and color.

2. In certain parts of the United States of America our race is denied the right of public trial accorded to other races when accused of crime, but are lynched and burned by mobs, and such brutal and inhuman treatment is even practiced upon our women.

3. That European nations have parcelled out among them and taken possession of nearly all of the continent of Africa, and the natives are compelled to surrender their lands to aliens and are treated in most instances like slaves.

4. In the southern portion of the United States of America, although citizens under the Federal Constitution, and in some States almost equal to the whites in population and are qualified land owners and taxpayers, we are, nevertheless, denied all voice in the making and administration of the laws and are taxed without representation by the State governments, and at the same time compelled to do military service in defense of the country.

5. On the public conveyances and common carriers in the southern portion of the United States we are jim-crowed and compelled to accept separate and inferior accommodations and made to pay the same fare charged for first-class accommodations, and our families are often humiliated and insulted by drunken white men who habitually pass through the jim-crow cars going to the smoking car.

6. The physicians of our race are denied the right to attend their patients while in the public hospitals of the cities and States where they reside in certain parts of the United States.

Our children are forced to attend inferior separate schools for shorter terms than white children, and the public school funds are unequally divided between the white and colored schools.

7. We are discriminated against and denied an equal chance to earn wages for the support of our families, and in many instances are refused admission into labor unions and nearly everywhere are paid smaller wages than white men.

8. In the Civil Service and departmental offices we are everywhere discriminated against and made to feel that to be a black man in Europe, America and the West Indies is equivalent to being an outcast and a leper among the races of men, no matter what the character attainments of the black men may be.

9. In the British and other West Indian islands and colonies Negroes are secretly and cunningly discriminated against and denied those fuller rights of government to which white citizens are appointed, nominated and elected.

10. That our people in those parts are forced to work for lower wages than the average standard of white men and are kept in conditions repugnant to good civilized tastes and customs.

11. That the many acts of injustices against members of our race before the courts of law in the respective islands and colonies are of such nature as to create disgust and disrespect for the white man’s sense of justice.

12. Against all such inhuman, unchristian and uncivilized treatment we here and now emphatically protest, and invoke the condemnation of all mankind.

In order to encourage our race all over the world and to stimulate it to overcome the handicaps and difficulties surrounding it, and to push forward to a higher and grander destiny, we demand and insist on the following Declaration of Rights:

1. Be it known to all men that whereas all men are created equal and entitled to the rights of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness, and because of this we, the duly elected representatives of the Negro peoples of the world, invoking the aid of the just and Almighty God, do declare all men, women and children of our blood throughout the world free denizens, and do claim them as free citizens of Africa, the Motherland of all Negroes.

2. That we believe in the supreme authority of our race in all things racial; that all things are created and given to man as a common possession; that there should be an equitable distribution and apportionment of all such things, and in consideration of the fact that as a race we are now deprived of those things that are morally and legally ours, we believed it right that all such things should be acquired and held by whatsoever means possible.

3. That we believe the Negro, like any other race, should be governed by the ethics of civilization, and therefore should not be deprived of any of those rights or privileges common to other human beings.

4. We declare that Negroes, wheresoever they form a community among themselves should be given the right to elect their own representatives to represent them in Legislatures, courts of law, or such institutions as may exercise control over that particular community.

5. We assert that the Negro is entitled to even-handed justice before all courts of law and equity in whatever country he may be found, and when this is denied him on account of his race or color such denial is an insult to the race as a whole and should be resented by the entire body of Negroes.

6. We declare it unfair and prejudicial to the rights of Negroes in communities where they exist in considerable numbers to be tried by a judge and jury composed entirely of an alien race, but in all such cases members of our race are entitled to representation on the jury.

7. We believe that any law or practice that tends to deprive any African of his land or the privileges of free citizenship within his country is unjust and immoral, and no native should respect any such law or practice.

8. We declare taxation without representation unjust and tyran[n]ous, and there should be no obligation on the part of the Negro to obey the levy of a tax by any law-making body from which he is excluded and denied representation on account of his race and color.

9. We believe that any law especially directed against the Negro to his detriment and singling him out because of his race or color is unfair and immoral, and should not be respected.

10. We believe all men entitled to common human respect and that our race should in no way tolerate any insults that may be interpreted to mean disrespect to our race or color.

11. We deprecate the use of the term “nigger” as applied to Negroes, and demand that the word “Negro” be written with a capital “N.”

12. We believe that the Negro should adopt every means to protect himself against barbarous practices inflicted upon him because of color.

13. We believe in the freedom of Africa for the Negro people of the world, and by the principle of Europe for the Europeans and Asia for the Asiatics, we also demand Africa for the Africans at home and abroad.

14. We believe in the inherent right of the Negro to possess himself of Africa and that his possession of same shall not be regarded as an infringement of any claim or purchase made by any race or nation.

15. We strongly condemn the cupidity of those nations of the world who, by open aggression or secret schemes, have seized the territories and inexhaustible natural wealth of Africa, and we place on record our most solemn determination to reclaim the treasures and possession of the vast continent of our forefathers.

16. We believe all men should live in peace one with the other, but when races and nations provoke the ire of other races and nations by attempting to infringe upon their rights[,] war becomes inevitable, and the attempt in any way to free one’s self or protect one’s rights or heritage becomes justifiable.

17. Whereas the lynching, by burning, hanging or any other means, of human beings is a barbarous practice and a shame and disgrace to civilization, we therefore declare any country guilty of such atrocities outside the pale of civilization.

18. We protest against the atrocious crime of whipping, flogging and overworking of the native tribes of Africa and Negroes everywhere. These are methods that should be abolished and all means should be taken to prevent a continuance of such brutal practices.

19. We protest against the atrocious practice of shaving the heads of Africans, especially of African women or individuals of Negro blood, when placed in prison as a punishment for crime by an alien race.

10. We protest against segregated districts, separate public conveyances, industrial discrimination, lynchings and limitations of political privileges of any Negro citizen in any part of the world on account of race, color or creed, and will exert our full influence and power against all such.

21. We protest against any punishment inflicted upon a Negro with severity, as against lighter punishment inflicted upon another of an alien race for like offense, as an act of prejudice and injustice, and should be resented by the entire race.

22. We protest against the system of education in any country where Negroes are denied the same privileges and advantages as other races.

23. We declare it inhuman and unfair to boycott Negroes from industries and labor in any part of the world.

24. We believe in the doctrine of the freedom of the press, and we therefore emphatically protest against the suppression of Negro newspapers and periodicals in various parts of the world, and call upon Negroes everywhere to employ all available means to prevent such suppression.

25. We further demand free speech universally for all men.

26. We hereby protest against the publication of scandalous and inflammatory articles by an alien press tending to create racial strife and the exhibition of picture films showing the Negro as a cannibal.

27. We believe in the self-determination of all peoples.

28. We declare for the freedom of religious worship.

29. With the help of Almighty God we declare ourselves the sworn protectors of the honor and virtue of our women and children, and pledge our lives for their protection and defense everywhere and under all circumstances from wrongs and outrages.

30. We demand the right of an unlimited and unprejudiced education for ourselves and our posterity forever[.]

31. We declare that the teaching in any school by alien teachers to our boys and girls, that the alien race is superior to the Negro race, is an insult to the Negro people of the world.

32. Where Negroes form a part of the citizenry of any country, and pass the civil service examination of such country, we declare them entitled to the same consideration as other citizens as to appointments in such civil service.

33. We vigorously protest against the increasingly unfair and unjust treatment accorded Negro travelers on land and sea by the agents and employee of railroad and steamship companies, and insist that for equal fare we receive equal privileges with travelers of other races.

34. We declare it unjust for any country, State or nation to enact laws tending to hinder and obstruct the free immigration of Negroes on account of their race and color.

35. That the right of the Negro to travel unmolested throughout the world be not abridged by any person or persons, and all Negroes are called upon to give aid to a fellow Negro when thus molested.

36. We declare that all Negroes are entitled to the same right to travel over the world as other men.

37. We hereby demand that the governments of the world recognize our leader and his representatives chosen by the race to look after the welfare of our people under such governments.

38. We demand complete control of our social institutions without interference by any alien race or races.

39. That the colors, Red, Black and Green, be the colors of the Negro race.

40. Resolved, That the anthem “Ethiopia, Thou Land of Our Fathers etc.,” shall be the anthem of the Negro race. . . .

41. We believe that any limited liberty which deprives one of the complete rights and prerogatives of full citizenship is but a modified form of slavery.

42. We declare it an injustice to our people and a serious Impediment to the health of the race to deny to competent licensed Negro physicians the right to practice in the public hospitals of the communities in which they reside, for no other reason than their race and color.

43. We call upon the various government[s] of the world to accept and acknowledge Negro representatives who shall be sent to the said governments to represent the general welfare of the Negro peoples of the world.

44. We deplore and protest against the practice of confining juvenile prisoners in prisons with adults, and we recommend that such youthful prisoners be taught gainful trades under human[e] supervision.

45. Be it further resolved, That we as a race of people declare the League of Nations null and void as far as the Negro is concerned, in that it seeks to deprive Negroes of their liberty.

46. We demand of all men to do unto us as we would do unto them, in the name of justice; and we cheerfully accord to all men all the rights we claim herein for ourselves.

47. We declare that no Negro shall engage himself in battle for an alien race without first obtaining the consent of the leader of the Negro people of the world, except in a matter of national self-defense.

48. We protest against the practice of drafting Negroes and sending them to war with alien forces without proper training, and demand in all cases that Negro soldiers be given the same training as the aliens.

49. We demand that instructions given Negro children in schools include the subject of “Negro History,” to their benefit.

50. We demand a free and unfettered commercial intercourse with all the Negro people of the world.

51. We declare for the absolute freedom of the seas for all peoples.

52. We demand that our duly accredited representatives be given proper recognition in all leagues, conferences, conventions or courts of international arbitration wherever human rights are discussed.

53. We proclaim the 31st day of August of each year to be an international holiday to be observed by all Negroes.

54. We want all men to know that we shall maintain and contend for the freedom and equality of every man, woman and child of our race, with our lives, our fortunes and our sacred honor.

These rights we believe to be justly ours and proper for the protection of the Negro race at large, and because of this belief we, on behalf of the four hundred million Negroes of the world, do pledge herein the sacred blood of the race in defense, and we hereby subscribe our names as a guarantee of the truthfulness and faithfulness hereof, in the presence of Almighty God, on this 13th day of August, in the year of our Lord one thousand nine hundred and twenty.

Source: UNIA Declaration of Rights of the Negro Peoples of the World, New York, August 13, 1920. Reprinted in Robert Hill, ed., The Marcus Garvey and Universal Negro Improvement Papers, vol. 2 (Berkeley, University of California Press, 1983), 571–580.

For this Opposition Jigsaw, create groups of three students and assign each to study a different opposition that Garvey encountered as described in one of the sources. Have students read/annotate/examine the sources for their area of focus and answer the following questions:

There are three source sets, each representing a different controversy or opposition related to Garvey:

1)FBI & J Edgar Hoover

2)W.E.B. DuBois

3)Concerns about Garvey and the Ku Klux Klan

After students have examined the documents, have them meet briefly (10-15 minutes) in a caucus with others who examined the same sources to review their responses/understanding to source Set Specific Questions:

Then have students return to their original groups and have mini–seminars (using specific evidence from their source) to share their new knowledge and understandings as well as to engage in discussion around similarities and differences.

The Negro is Ready

We are organized for the absolute purpose of bettering our condition, industrially, commercially, socially, religiously and politically. We are organized not to hate other men, but to lift ourselves, and demand respect of all humanity, We have a program that we believe to be righteous; we believe it to be just, and we have made up out minds to lay down ourselves on the altar of sacrifice for the realization of this great hope of ours, based upon the foundation of righteousness. We declare to the world that Africa must be free, that the entire Negro race must be emancipated from industrial bondage, peonage and serfdom; we make no compromise, we make to apology in this our declaration. We do not desire to create offense on the part of other races, but we are determined that we shall be heard, that we shall be given the rights to which we are entitled….

Deceiving the People

There is many a leader of our race who tells us that everything is well and that all things will work out themselves and that a better day is coming. Yes, all of us know that a better day is coming; we all know that one day we will go home to Paradise, but whilst we are hoping by our Christian virtues to have an enter into Paradise we also realize that we are living on earth an that the things that are practiced in Paradise are not practiced here. You have to treat this world as the world treats you; we are living in a temporal, material age, an age of activity, and age of racial, national selfishness. What else can you expect but to give back to the world what the world gives to you, and we are calling upon the four hundred million Negroes of the world to take a stand, that we shall occupy a firm position; that position shall be an emancipated race and a free nation of our position; that position shall be an emancipated race and a free nation of our own. We are determined that we shall have a free country; we are determined that we shall have a flag we are determined that we shall have a government second to none in the world.

An Eye for an Eye

Men may spurn the idea, they may scoff at it, the metropolitan press of this country may deride us; yes, white men may laugh at the idea of Negroes talking about government; but let me tell you there is going to be a government, and let me say to you also that whatsoever you give, in like measure it shall be returned to you. The world is sinful, and therefore man believes in the doctrine of an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth. Everybody believes that revenge is God’s, but at the same time we are men, and revenge sometimes springs up, even in the most Christian heart.

Why should man write down a history that will react against him? Why should man perpetrate deeds of wickedness upon his brother which will return to him in like measure? Yes, the Germans maltreated the French in the Franco-Prussian war of 1870, but the French got even with the Germans in 1918. It is history, and history will repeat itself. Beat the Negro, brutalize the Negro, kill the Negro, burn the Negro, imprison the Negro, scoff at the Negro, deride the Negro, it may come back to you one of these fine days, because the supreme destiny of man is in the hands of God. God is no respecter of persons, whether that person be white, yellow or black. Today the one race is up, tomorrow it has fallen; today the Negro seems to be the footstool of the other races and nations of the world; tomorrow the Negro may occupy the highest rung of the great human ladder.

But, when we come to consider the history of man, was not the Negro a power, was he not great once? Yes, honest students of history can recall the day when Egypt, Ethiopia and Timbuctoo towered in their civilizations, towered above Europe, towered above Asia. When Europe was inhabited by a race of cannibals, a race of savages, naked men, heathens and pagans, Africa was peoples with a race of cultured black men, who were cultured and refined; men who, it was said, were like the gods. Even the great poets of old sang in beautiful sonnets of the delight it afforded the gods to be in companionship with the Ethiopians. Why, then; should we lose hope? Black men, you were once great; you shall be great again. Lose not courage, lose not faith, go froward. The ting to do is to get organized; keep separated and you will be exploited, you will be robbed, you will be killed. Get organized, and you will compel the world to respect you. If the world fails to give you consideration, because you are black men, because you are Negroes., four hundred millions of you shall, through organization, shale the pillars of the universe and bring down creation, even as Samson brought down the temple upon his head and upon the heads of the Philistines.

An Inspiring Vision

So Negroes, I say, through the Universal Negro Improvement Association, that there is much to live for. I have a vision of the future, and I see before me a picture of a redeemed Africa, with her dotted cities, with her beautiful civilization, with her millions of happy children, going to and fro. Why should I lose hope, why should I give up and take a back place in this age of progress? Remember that you are men, the God created you Lords of this creation. Lift up yourselves, men, rise as high as the very stars themselves. Let no man pull you down, let no man destroy your ambition, because man is but your companion, your equal; man is your brother; he is not your lord; he is not your sovereign master.

We of the Universal Negro Improvement Association feel happy; we are cheerful. Let them connive to destroy us; let them organize to destroy us; we shall fight the more. Ask me personally the cause of my success, and I say opposition; oppose me, and I fight the more, and if you want to find out the sterling worth of the Negro, oppose him, and under the leadership of the Universal Negro Improvement Association he shall fight his way to victory, and in the days to come, and I believe not far distant, Africa shall reflect a splendid demonstration of the worth of the Negro, of the determination of the Negro, to set himself free and to establish a government of his own.

Source: reprinted in Jacques-Garvey, Amy., ed. Philosophy and Opinions of MarcusGarvey: Volumes I and II. New York: Antheneum, 1923. Reprinted in 1969

Document 5.6.2: Excerpts from “The Future as I See It,” Marcus Garvey, 1923.

Washington, D.C., July 16—A united protest from many Negroes throughout the country against the recent conviction in New York of Marcus Garvey, Head of the Universal Negro Improvement Association, was voiced today in scores of telegrams addressed to the Washington office of the Associated Press.

Each of the messages represented sentiments said to have been expressed at a Negro mass meeting yesterday. They came from near’y every state and were identic except for the number of persons reported as in attendance at each local meeting.

“We, local Negro citizens of the United States,” said each message, “at mass meeting assembled, beg to register with our white citizens thru you, our protest against the injustice that has been done to Marcus Garvey, President General of the Universal Negro Improvement Association, his frame up conviction in New York, and denial of bail pending appeal.”

“We sincerely hope that the white press of our great country will turn on the searchlight of justice and thereby maintain the honor and glory of our fair institutions of justice.”

Various protests have been made by the White House and Department of Justice, but the department has announced that no action will be taken which will interfere with the handling of the case by the district court.

Document 5.6.7: “Plead for Marcus Garvey,” Union, July 28, 1923

Introduce students to the important role that women played in the U.N.I.A. that served as a distinguishing characteristics from other organizations of that time:

Throughout the history of the U.N.I.A., women powerfully resisted marginalization. Despite the relative lack of subsequent scholarship on female leaders, organizations and accomplishments it is known that each local division of the U.N.I.A had both a Lady President and Male President, though these differed by region in power distribution. Additionally, we know that three of the six directors in 1918 were women.

The group should ideally be given a class period to research their assigned/selected Woman of the U.N.I.A. using the internet or provided resources:

After completing their research, students should create a poster, presentation or written summary to present their answers to the following questions:

Resources accessible for student’s usage may include the following sources.

Students should read the Man Who Was Almost Made King and then consider and prepare to defend independently or in small groups, whether Marcus Garvey was a great hero and influential leader of African Americans or should his accomplishments be discredited due to his controversial beliefs and failures. Each group may reference the Vivian Morris reading as well as previously reviewed sources. (Note that the source is lengthy; you might choose shorter selections based on your own students’ needs, interests, and lesson time constraints.)

Excerpts from “The Man Who Was Almost Made King,” Federal Writers’ Project interview with Vivian Morris, October 1938

…His name was Marcus Garvey. He was born, so the records say, on the island of Jamaica in the British West Indies about 1887, but few people ever heard of him until he came to New York. He was a born orator and his power to attract and hold an audience was destined to make him famous.

I remember his first important speech.

"Wherever I go, whether it be France, Germany, England-or Spain, I am told that there is no room for a Negro. The other races have countries of their own and it is time for the 400,000,000 Negroes of the world to claim Africa for themselves. Therefore, we shall demand and expect of the world a Free Africa. The black man has been serf, a tool, a slave and peon long enough.

That day has ceased.

We have reached the time when every minute, every second must count for something done, something achieved in the cause for Africa. We need the freedom of Africa now. At this moment methinks, I see Ethiopia stretching forth her hands unto God, and methinks I see the Angel of God taking up the standard of the Red, the Black, and the Green, and sayings; Men of the Negro race, Men of Ethiopia, follow me:

"It falls to our lot to tear off the shackles that bind Mother Africa. Can you do it? You did it in the Revolutionary War. You did it in the Civil War. You did it in the battles of Maine and Verdum. You did it in the Mesopotamia. You can do it marching up the battle heights of Africa. Climb ye the heights of liberty and cease not in well-doing until you have planted the banner of the Red, the Black, and the Green upon the hilltops of Africa

These, my child, were the very words of the man Marcus Garvey, whom many called the black Napoleon. I Remember them well as you, perhaps, remember Lincoln's Gettysburg address. He was standing there, strong and forceful before a crowd of more than 25,000 Negroes who had assembled in Madison Square Garden to consider the problems of the Negro race. It was shortly after the World War, August 1920 I believe.

Well that was a sight to thrill you with pride. Imagine, huge spacious Madison Square Garden, rocking with the yells of 25,000 frenzied Negro patriots demanding a free Africa, from the Strait of Gibraltar to the cape of Good Hope-- A Negro republic run exclusively by and for Negroes. Doesn't sound real, does it? Well, it happened--and it can happen again, but not until another leader with Marcus Garvey's strength, vision and courage comes along. Some people say that Father Divine is the answer to this need. Personally I doubt it. He is a good organizer but his Divinities are not to be compared with the powerful and vigorous following once commanded by the Universal Negro Improvement Association that Garvey founded and built single-handed. Why, He had such a magnetic personality that people flocked to see him wherever he went, and when he appeared on any platform to speak he'd have to wait sometimes five or ten minutes before the loud ovations an sounds of applause subsided. Then he would stride majestically forward in his cap and gown of purple, green and gold, and the hall, arena, square, or whatever it was, would become magically silent.

He was always an enigma to the white people who flocked, in great numbers, to hear him, They couldn't decide whether to consider him a political menace or a harmless buffoon. But to his several hundred thousand Negro followers he was a great leader with a wonderful idea, an unequalled program of emancipation. He did not claim to be a great intellectual, a Frederick Douglas or Booker T. Washington, but he was certainly endowed with color and originality; so much so that he caught the fancy and commanded the solid support of the Negro masses, as no other man has done before or since. He had the unusual happy faculty for stirring their race consciousness.

I can see him even now as he stood and exhorted his followers at that first organizational meeting.

He read a telegram of greeting To Eamon De Valera, President of the Irish Republic, Wait a minute, I'll look among my papers and find a copy of it for you.

Here it is. It says; "25,000 Negro delegates assembled in Madison Square Garden in Mass Meeting, representing 4000,000,000 Negroes of the world, send you greetings as President of the Irish Republic Please accept sympathy of the Negroes of the world for your cause We believe Ireland should be free even as Africa shall be free for the Negroes of the world. Keep up the fight for a free Ireland."

After that, he spoke at length and if I remember correctly, his speech went something like this;

"We are descendants of a suffering people. We are descendants of a people determined to suffer no longer. Our forefathers suffered many years of abuse from an alien race……

….Fifty-five years ago the black man was set free from slavery on this continent. Now he declares that what is good for the white man of this age is also good for the Negro. They as a race, claim freedom, and claim the right to establish a democracy. We shall now organize the 400,000,000 Negroes of the World into a vast organization to plant the banner of freedom on the great continent of Africa. We have no apologies to make, and will make none. We do not desire what has belonged to others, though others have always sought to deprive us of that which belonged to us.

We new Negroes will dispute every inch of the way until we win.

We will begin by framing a bill of rights of the Negro race with a constitution to guide the life and destiny of the 400,000,000. The Constitution of the United States means that every white American would shed his blood to defend that Constitution. The constitution, of the Negro race will mean that every Negro will shed his blood to defend his Constitution.

If Europe is for the Europeans, then Africa shall be for the black peoples of the world, We say it. We mean it."

Following the thirty day organizational convention of the Universal Negro Improvement Association at Madison Square Garden, more than three thousand delegates and sympathizers of the group gathered in Harlem at Liberty Hall, 140 West 138 Street, where they gave their final approval of the declaration of rights of the Negro peoples of the world. Delegates were there from Africa as well as the West Indian and Bermuda Islands. It was a memorable occasion.

Decorating the huge hall were banners of the various delegations. Prominently displayed also were the red, black and green flags of the new African [Republic-to-be]. A colorful, forty piece band, a choir of fifty male and female voices and several quartettes entertained the assembly all during the early part of the evening. Afterwards, Marcus Garvey, president general of the association, announced the business of the meeting and read the declaration.

Much applause greeted the reading of the preamble to the declaration which stated: "In order to encourage our race all over the world and to stimulate it to overcome the handicaps and difficulties surrounding it, and to push forward to a higher and grander destiny, we demand and insist upon the following declaration of rights."

Then followed the fifty four statements of rights that the association demanded for Negroes everywhere. The first was similar in form to the American Declaration of Independence. It read: "Whereas all men are created equal and entitled to the rights of life, liberty and the pursuits of happiness, and because of this, we, dully elected representatives of the Negro people of the world, invoking the aid of the just and almighty God, do declare all men, women and children of our blood throughout the world free denizens, and do claim them as free citizens of Africa, the motherland of all Negroes."

The first statement was greeted with loud and prolonged applause, as were many others that followed it, but there was so much enthusiasm, shouting, stamping of feet and other exhibitions of approval at the conclusion of the following statement that the chairman was forced to appeal, again and again for order. It read: "We declare that no Negro shall engage himself in battle for an alien race without first obtaining consent of the leader of the Negro peoples of the world, except in a matter of national self-defense."

Another statement which met with popular fancy was: "We assert that the Negro is entitled to even-handed justice before all courts of law and equity, in whatever country he may be found, and when this is denied him on account of his race or color, such denial is an insult to the race as a whole, and should be resented by the entire body of Negroes.

"We deprecate the use of the term 'nigger' as applied to Negroes and demand that the word 'negro' be written with a Capital 'N'.

"We demand a free and unfettered commercial [intercourse] with all the Negro peoples of the world. We demand that the governments of the world recognize our leader and his representatives chosen by the race to look after the welfare of our people under such governments. We call upon the various governments to represent the general welfare of the Negro peoples of the world.

"We demand that our duly accredited representatives be given proper recognition in all leagues, conferences, conventions or courts of international arbitration whenever human rights are discussed.

"We proclaim the first day of August of each year to be an international holiday to be observed by all Negroes."

The thing that makes this ambitious adventure all the more remarkable, my child, is the fact that all these strong resolutions and gigantic plans were conceived entirely by this one man, Marcus Garvey, who, in the beginning, was just another underprivileged West Indian boy; a printer's apprentice. Fired with the idea of welding the divided black masses of the world together, however, he became an entirely different and revolutionary personality….

Nineteen seventeen saw the actual beginning of the Garvey movement but not until the Spring of nineteen eighteen did Marcus succeed in officially organizing the Universal Negro Improvement Association. Later, in the Fall, he established his own newspaper, The Negro World" and began a systematic appeal for contributions to the movement. It was also his medium for preaching his doctrines to the out of town public. Week by week the paper's editorial pages aired his opinions.

Soon, money began pouring into the coffers of the Association, and it was not long before Garvey organized a steamship company, known as the Black Star Line, and scheduled to operate between the West Indies, Africa and the United States. During the winter of 1919 alone, more than half a million dollars worth of stock was sold to Negroes. One Negro college in the state of Louisiana was reputed to have raised seven thousand dollars for promotion of the scheme. Three ships, Garvey said, had been bought from the entire proceeds of the national fund: The Yarmouth, the Maceo and line Shadysiah. Another, the Phyllis Wheatley, was advertised weekly in the Negro World. It was claimed that she would ply between Cuba, St. Kitts, Barbadoes, Trinidad, Demerara, Dakar and Monrovia. The only hitch was, the date of sailing never came. In fact, the mass inspection of the Phyllis Wheatley that Garvey kept promising his followers, never came. Certain doubters in the organization then began to wonder whether there was any ship at all they went even further than that. They sent a delegation to His Highness, the President, with a demand to see the boat. Garvey, always at ease in the face of any difficult situation, that them that he would attend to it the next day. When the next day came, he put them off again. And so it went from day to day.

This difficult situation arose during the famous "first convention" that was held in August 1920 and lasted for thirty days. There was a grand and imposing parade through the streets of Harlem and the colorful, regal mass meetings at Madison Square Garden and Liberty Hall. Garvey said he was busy. There was nothing for the delegates to do but wait. The publicity that the movement received during this gigantic display of marching legions and blaring trumpets, skyrocketed the circulation of the "Negro World" to the amazing figure of 75,000 unprecedented in the field of weekly Negro journalism. It was one of the instruments that made Garvey the most powerful black man in America at that time. Harlem and black America were literally at his feet.

Garvey then bought a chain of grocery stores, restaurants, beauty and barber shops, laundries, women’s' wear shops, and a score or more of other small businesses. He instituted a one-man campaign to completely monopolize the small industries in Harlem and drive the white store-keepers out. His one big mistake came, however, when he printed and issued circulars asking for additional purchasers of Black Star Line stock and assuring prospective buyers of the financial soundness of the company. This was too much for the delegates who had been asking for a detailed accounting of the Associations' funds throughout the entire convention only to get the run around. They immediately petitioned the U. S. Post Office Department of Inspection to investigate the company’s books. When the true state of affairs was brought to light, Garvey was immediately indicted for using the mails to defraud. The investigation also brought to light the fact that Garvey had collected thousand of dollars for his so called "defense fund".

Well, to make a long story short, by June 1924, instead of perching majestically on his golden throne in some far away jungle clearing, being waited and danced attendance upon by titled nobles, the erstwhile Black Napoleon and Provisional President of Africa, found himself sitting, disconsolate and alone, in a bare cell of the Tombs prison. It was the culmination of a 27 day trail in the United States District Court. The jury, after listening to testimony and arguments for practically the entire duration of that time, brought in a verdict of 'guilty'. Marcus, the great, had been duly and officially convicted of using the mails to defraud.

Loyal officers of the movement had a bail bondsman on hand, ready to secure the release of their idol but the Assistant U. S. District Attorney foiled this move by asking that Garvey be remanded to prison without bail. His [request?] was granted when the Court was told that Garvey's African Legion was well supplied with guns and ammunition and would probably help their chief to escape.

And so, in the midst of heavily armed U. S. Marshalls and a detachment of New York City policemen, the "Leader of the Negro Peoples of the World", was marched off to the, anything but comfortable and homelike, atmosphere, of the Tombs. Later he was transferred to Atlanta. With him went his dreams of a great Black Empire, his visions of a final welding of all Negroes into one strong, powerful nation, with himself as dictator; his favorite supporters, elegant lords, princes, dukes and other personages of high-sounding title: like "High Commissioner", "His Highness and Royal Potentate", "Minister of the African Legion", "The Right Honorable High Chancellor", "His Excellency, Prince of Uganda", "Lord of the Nile" and so on.

Yes, there's no doubt about it, Garvey had grandiloquent ideas. Conceiving and attempting to put over big things was his specialty. But like most dreamers, he dreamed just a little too much. He was too little the realist. Otherwise, his story might have been different. As it was, few of his dreams ever came true; not, mind you, of their lack of soundness. I still feel that he was a great man, honest and sincere. But he was not practical. Conducting a business enterprise according to established rules meant very little to him. That was his undoing. But there was no denying the fact that he was a colorful personality. The way he thought up such grand titles for his subjects was only one manifestation of it. In defense of conferring these titles, by the way, Garvey said:

"It is human nature that when you make a man know that you are going to reward him and recognize and appreciate him for services rendered, and place him above others, he is going to do the best that is in him."

Garvey also called attention to the fact that the conferring of degrees by colleges and universities adopted from European customs, is only parallel to the conferring of titles by the Universal Negro Improvement Association. The only difference being that one is scholastic, the other political. And, perhaps he was right.

Document 5.6.8

In 1937, during a speech titled The Work That Has Been Done, Marcus Garvey stated “Emancipate yourself from mental slavery… none but ourselves can free our minds…”. More than forty years later, fellow Jamaican Bob Marley, went on to utilize this line in his famous song Redemption Song. This song written by Marley contained Garvey’s famous quote within its lyrics.

Listen to Redemption Song in its entirety in order to write an essay exploring the connection between these two figures.

In 2019, many individuals participated in what was known as the Year of Return. This was an initiative organized by the government of Ghana alongside American based cultural groups, that encouraged those of the African diaspora to return to Africa to settle and invest in the continent.

What do you think Garvey would identify as the next step or next initiative to follow the Year of Return?

Please login or sign up to access the student view functions.