Unit

Years: 1846-1857

Culture & Community

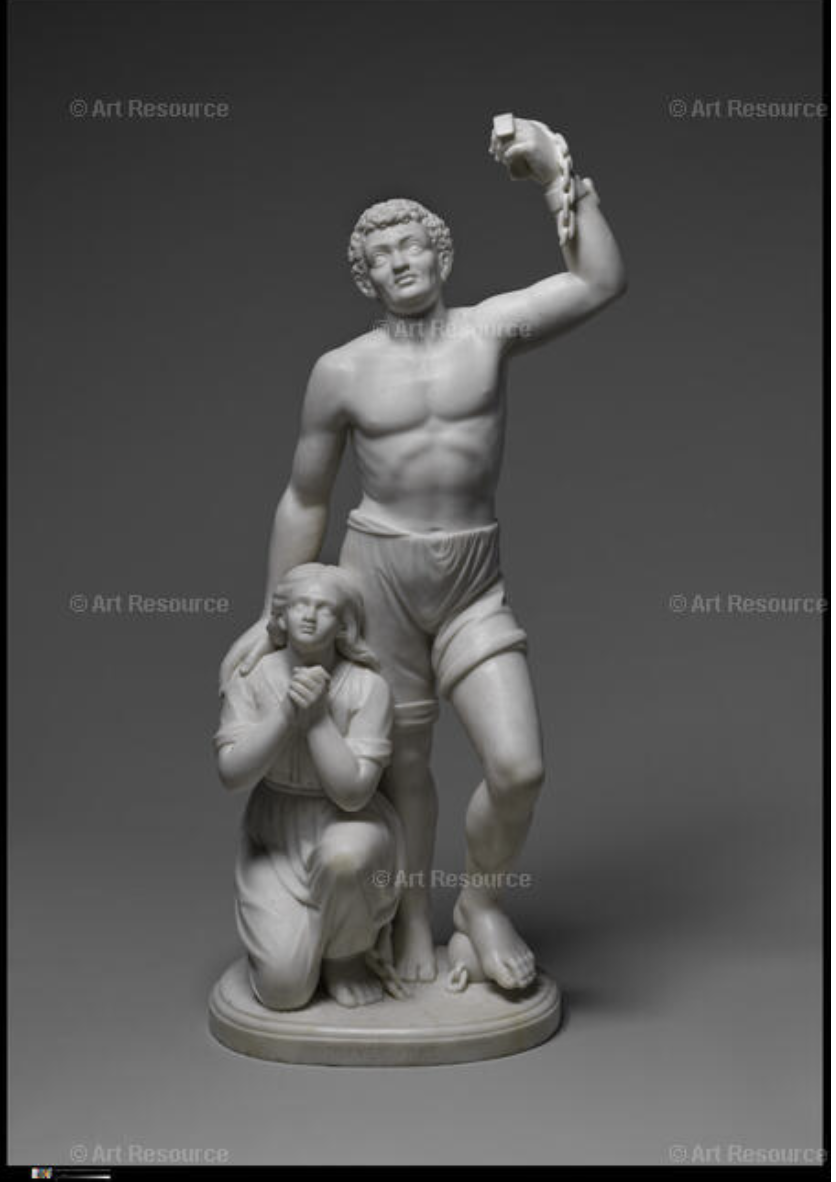

The end of the Civil War and the passage of the 13th Amendment to the Constitution brought an end to enslavement across the United States. But emancipation–the freedom from bondage–had different effects on different people. For some formerly enslaved people, emancipation meant the freedom to define themselves outside of the system of enslavement by choosing a new name, enrolling in school, getting legally married, and reuniting with family. For others, emancipation brought continued racial discrimination, violence, and repression.

Emancipation came with its own set of opportunities, as well as new obstacles that Black Americans had to overcome to live truly free lives. The federal government created the Freedmen’s Bureau to assist formerly enslaved people in meeting these challenges and opportunities. The Freedmen’s Bureau supported Black Americans in finding their loved ones, set up public schools for Black children and adults, and distributed resources to formerly enslaved people who had few personal belongings. But the Freedmen’s Bureau and other government agencies–including the U.S. military–also limited the opportunities that Black people could pursue by enforcing exploitative sharecropping agreements, keeping Black soldiers from returning to their families, and failing to enshrine legal protections for Black Americans during the brief period of Reconstruction. For many formerly enslaved Black Americans, the promise of emancipation did not quite match its reality.

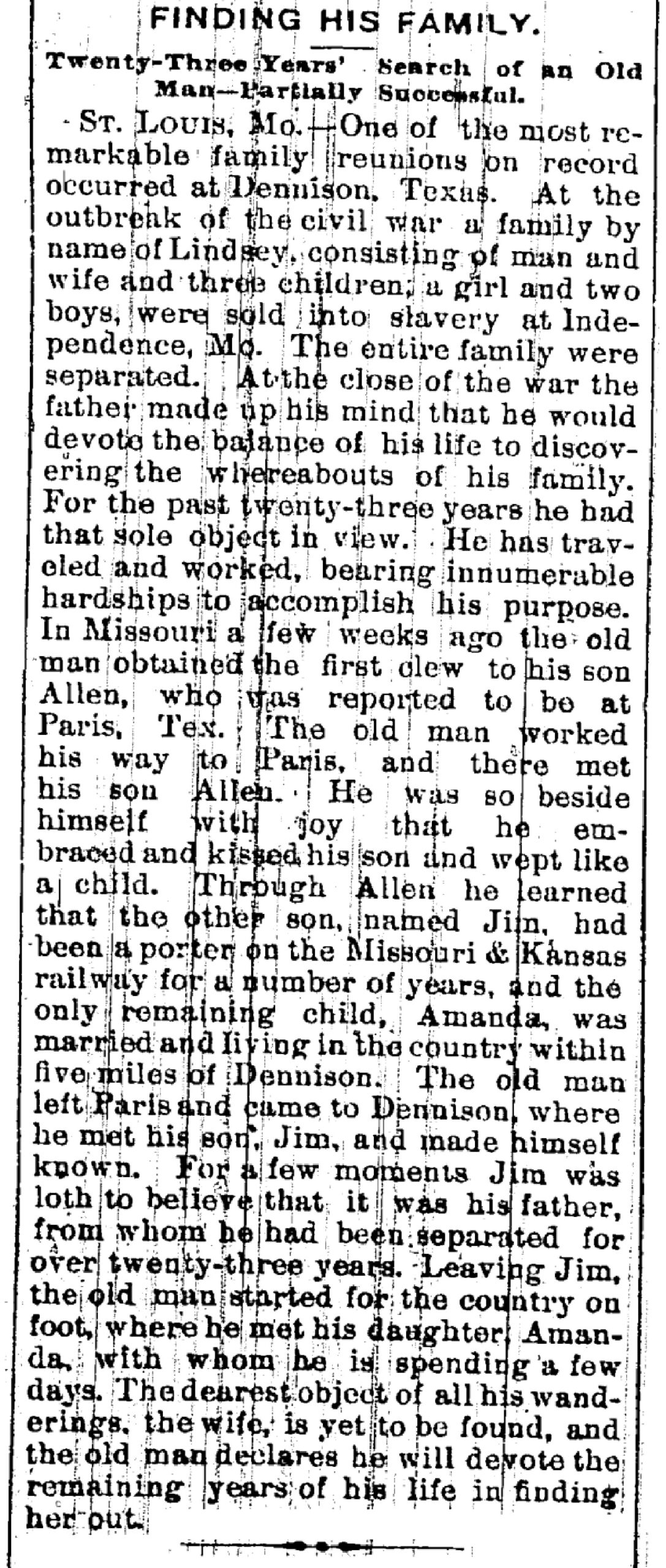

Advertisements seeking relatives, the Colored Tennesseean, Nashville, 1865.

Earlier in the nineteenth century, when huge plantations were created in the Deep South, slave owners broke up thousands of African American slave families to fill the need for labor. Once emancipated, freedpeople began to search for sons, daughters, husbands, wives, and parents. African American newspapers frequently carried advertisements such as the ones below.

Information Wanted of Caroline Dodson, who was sold from Nashville, Nov. 1st, 1862, by James Lumsden to Warwick (a trader then in human beings), who carried her to Atlanta, Georgia, and she was last heard of in the sale pen of Robert Clarke, (human trader in that place), from which she was sold. Any information of her whereabouts will be thankfully received and rewarded by her mother. Lucinda Lowery, Nashville.

-----------------------

$200 Reward. During the year 1849, Thomas Sample carried away from this city, as his slaves, our daughter, Polly, and son, Geo. Washington, to the State of Mississippi, and subsequently, to Texas, and when last heard from they were in Lagrange, Texas. We will give $100 each for them to any person who will assist them, or either of them, to get to Nashville, or get word to us of their whereabouts, if they are alive. Ben & Flora East.

-----------------------

Saml. Dove wishes to know of the whereabouts of his mother, Areno, his sisters Maria, Neziah, and Peggy, and his brother Edmond, who were owned by Geo. Dove, of Rockingham county, Shenandoah Valley, Va. Sold in Richmond, after which Saml. and Edmond were taken to Nashville, Tenn., by Joe Mick; Areno was left at the Eagle Tavern, Richmond. Respectfully yours, Saml. Dove, Utica, New York!

Source: Reprinted in Smith, John David. Black Voices from Reconstruction: 1865-1877. Brookfield, CT: The Millbrook Press, 1996, 51-2. (Document 4.7.9)

Letter from the Wife of a Michigan Black Soldier to the Secretary of War, May 11, 1865.

Detroit May 11 1865

Dear sir I have taken the Liberty to write you afew lines which I am compelled to do I am colored it is true but I have feeling as well as white person and why is it the colored soldiers letters cant pass backward and fowards as well as the white ones Mr Stanton Dear sir I think it very hard We cant get any letters and I wish would please look in this matter and have things arranged so we can hear from our Husband if we cant see them I have not heard from my Husband in three months John Bailey is my husband he was Drum major of the 100th united States Colored Troops he went from Detroit he is the man Senator Howard wrote to you about last summer and tried to get afurlogh for him Then he was sick I have hurd through others he was very sick and since that I have heard he was dead if he is living I wish you would please grant him afurlogh to come home he was promised one when he went away and he has been gone over a year and I do wish you would be so kind as to let him come home if he is living I wish you would look oar your Books and see if he is alive I dont know who to write to only you President Lincoln is gone and he was our best friend and now we look to you and I hope God will wach over and protect you through this war

Please write me as soon as you get this Direct to Mrs. Lucy Bailey 190 Congress Street 190

Source: reprinted in Berlin, Ira, Barbara Fields, Steven Miller, Joseph P. Reidy and Leslie S. Rowland, ed. Free At Last: A Documentary History of Slavery, Freedom and the Civil War. New York: New Press, 1992. (Document 4.7.10)

Report from army chaplain A.B. Randall, attached to a regiment of Black soldiers in Little Rock, Arkansas, 1865

Denied legal marriage under slavery, many freedpeople quickly sought to legalize longstanding relationships. Clergymen—particularly the Union army chaplains present throughout much of the South—found themselves in great demand. A.B. Randall was an army chaplain with a Black regiment in Arkansas.

Little Rock Ark Feb 28th 1865

Weddings, just now, are very popular, and abundant among the Colored People. They have just learned of the Special Order No. 15 of Gen. Thomas by which, they may not only be lawfully married, but have their Marriage Certificates Recorded; in a book furnished by the Government. This is most desirable; and the order, was very opportune as these people were constantly losing their certificates. Those who were captured from the “Chepewa” at Ivy’s Ford on the 17th of January, by Col. Brooks, had their Marriage Certificates taken from them and destroyed; and then were roundly cursed for having such papers in their possession. I have married, during the month at this Post, Twenty five couples, mostly those who have families and have been living together for years. I try to dissuade single men who are soldiers from marrying until their time of enlistment is out, as that course seems to me to be most judicious.

The Colored People here, generally consider, this war not only; their exodus from bondage, but the road to Responsibility; Competency; and honorable Citizenship—God grant that their hopes and expectations may be fully realized. Most Respectfully

A.B. Randall

Source: Reprinted in Berlin, Ira and Leslie S. Rowland, eds. Families and Freedom: A Documentary History of African American Kinship in the Civil War Era. New York: New Press, 1997. 163. (Document 4.12.1)

Freedwoman’s letter to her husband who had been seeking her. April 7, 1866

Across the former slave states, freedpeople went about the monumental task of reuniting families, which had been torn apart by slavery. Phillip Grey, a freedman of Virginia, found his wife, Willie Ann, and their daughter in Kentucky. However, after their involuntary separation, Willie Ann had remarried and had three additional children by her second husband. He died serving in the Union army. To Phillip Grey, she wrote:

Salvisa KY April 7th 1866

Dear Husband,

I seat myself this morning to write you a few lines to let you know that I received your letter the 5 of this month and was very glad to hear from you and to hear that you was well. This leaves us all well at present and I hope these lines may find you still in good health. You wish me to come to Virginia. I had much rather that you would come after me but if you cannot make it convenient you will have to make some arrangements for me and the family. I have 3 little fatherless girls. My husband went off under Burbridges command and was killed at Richmond, VA. If you can pay my passage through there I will come the first of May. I have nothing much to sell as I have had my things all burnt so you know that what I would sell would not bring much. You must not think my family too large and get out of heart for if you love me you will love my children and you will have to promise me that you will provide for them all as well as if they were your own. I heard that you spoke of coming for Maria but was not coming for me. I know that I have lived with you and loved you then and I love you still. Every time I hear from you my love grows stronger. I was very low spirited when I heard that you was not coming for me. My heart sank within me in an instant. You will have to write and give me directions how to come. I want when I start to come the quickest way that I can come. I do not want to be detained on the road. If I was the expense would be high and I would rather not have much expense on the road. Give me directions which is the nearest way so that I will not have any trouble after I start from here. Phebe wishes to know what has become of Lawrence. She heard that he was married but did not know whether it was so or not. Maria sends her love to you but seems to be low spirited for fear that you will come for her and not for me. John Phebe’s son says he would like to see his father but does not care about leaving his mother who has taken care of him up to this time. He thinks that she needs help and if he loves her he will give her help. I will close now by requesting you write as soon as you receive this so no more at present but remain your true (I hope to be with you soon) wife.

Willie Ann. Grey

To Phillip Grey

Aunt Lucinda sends her love to you. She has lost her husband and one daughter, Betsy. She left 2 little children. The rest are all well at present. Pheby’s Mary was sold away from her. She heard from her the other day. She was well.

Direct your letters to Mrs. Mollie Roche Salvisa KY

Source: Reprinted in Berlin, Ira and Leslie S. Rowland, eds. Families and Freedom: A Documentary History of African American Kinship in the Civil War Era. New York: New Press, 1997. 173. (Document 4.12.4)

Report from army chaplain A.B. Randall, attached to a regiment of Black soldiers in Little Rock, Arkansas, 1865

Denied legal marriage under slavery, many freedpeople quickly sought to legalize longstanding relationships. Clergymen—particularly the Union army chaplains present throughout much of the South—found themselves in great demand. A.B. Randall was an army chaplain with a Black regiment in Arkansas.

Little Rock Ark Feb 28th 1865

Weddings, just now, are very popular, and abundant among the Colored People. They have just learned of the Special Order No. 15 of Gen. Thomas by which, they may not only be lawfully married, but have their Marriage Certificates Recorded; in a book furnished by the Government. This is most desirable; and the order, was very opportune as these people were constantly losing their certificates. Those who were captured from the “Chepewa” at Ivy’s Ford on the 17th of January, by Col. Brooks, had their Marriage Certificates taken from them and destroyed; and then were roundly cursed for having such papers in their possession. I have married, during the month at this Post, Twenty five couples, mostly those who have families and have been living together for years. I try to dissuade single men who are soldiers from marrying until their time of enlistment is out, as that course seems to me to be most judicious.

The Colored People here, generally consider, this war not only; their exodus from bondage, but the road to Responsibility; Competency; and honorable Citizenship—God grant that their hopes and expectations may be fully realized. Most Respectfully

A.B. Randall

Source: Reprinted in Berlin, Ira and Leslie S. Rowland, eds. Families and Freedom: A Documentary History of African American Kinship in the Civil War Era. New York: New Press, 1997. 163. (Document 4.12.1)

The Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, ratified in 1865, abolished slavery and involuntary servitude, except as punishment for a crime. It was a crucial step in ending institutionalized slavery in the United States following the Civil War and emancipating millions of enslaved individuals.

The act of setting free or liberating someone from slavery, servitude, or oppression, often through legal or formal means.

An executive order issued by President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863, during the Civil War, declaring that all enslaved people in Confederate-controlled territory were to be freed.

The period in American history following the Civil War, approximately from 1865 to 1877, where efforts were made to rebuild and transform the Southern states that had seceded from the Union. It aimed to address issues such as the integration of formerly enslaved African Americans into society.

Also known as the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, a federal agency established by Congress in 1865 during the Reconstruction era to assist formerly enslaved African Americans and impoverished whites in the South with education, employment, health care, and other social services. The Freedmen's Bureau played a significant role in supporting the transition from slavery to freedom and promoting civil rights and equality in the post-Civil War South.

Provisions of food or supplies distributed by authorities or organizations, typically during times of scarcity, emergencies, or conflicts, to ensure that individuals or populations have access to essential resources to meet their basic needs.

Sharecropping was an agricultural system prevalent in the Southern United States after the Civil War, in which landless farmers, often formerly enslaved individuals, rented land and equipment from landowners in exchange for a share of the crops grown.

The 17th President of the United States (1865-1869) who succeeded Abraham Lincoln after his assassination and oversaw the early Reconstruction period following the Civil War.