Unit

Years: 1877 to 1950

Historical Events, Movements, and Figures

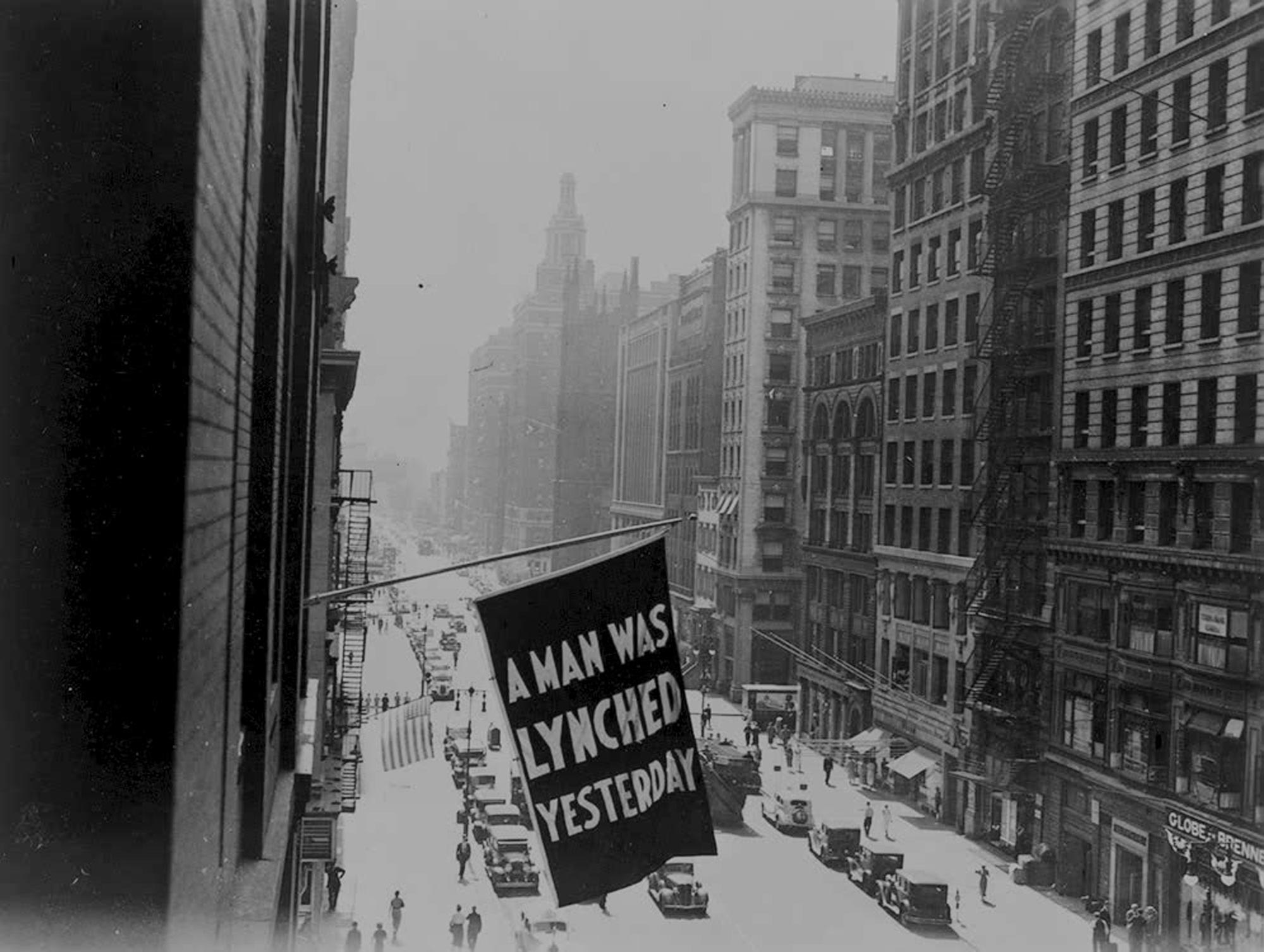

Lynching, a public execution committed by a group without any legal action or trial, was an extremely violent and traumatic reality for Black Americans living in Jim Crow America. Lynching amounted to racial terrorism, and White supremacists commonly tortured and killed their victims publicly while White audiences cheered them on. Not all victims of lynch mobs were Black, but the vast majority were, and the Equal Justice Initiative has documented over 4,000 lynchings of Black people between 1877 and 1950.

While journalist Ida B. Wells-Barnett published numerous articles to expose the horrors of lynching and hold public officials and institutions accountable, Congress and the courts failed to act. At the same time, Black Americans fought for justice in the court system. In the case of the “Scottsboro 9,” nine Black teenagers were falsely accused of rape and unjustly imprisoned. The Scottsboro 9 faced all-white juries, lynch mobs, and other legal barriers to accountability, but their case eventually led to new legal protections for Black citizens to access a free and fair trial. In the end, the anti-lynching campaign and Scottsboro case set the stage for broader activism in the civil rights movement.

Excerpts from “The Malicious and Untruthful White Press,” by Ida B. Wells, 1892

Ida B. Wells (1862–1931) was born in Holly Springs, Mississippi to enslaved parents, six months before the Emancipation Proclamation. She attended Rust College until her mother, father, and youngest sibling died in a yellow fever epidemic, at which time she took on the responsibility of supporting herself and her six younger brothers and sisters. She became a teacher.

In 1884, Wells was asked to move to the smoking car of a train on the way to her first teaching job. When she refused, two conductors tried to physically force her into the smoking section. She got off the train instead and filed a discrimination lawsuit. She was awarded $500 dollars, but the verdict was reversed three years later by Tennessee’s Supreme Court.

After Wells was fired from her teaching position because she wrote an editorial accusing the Memphis school board of not providing enough resources for black schools, she turned to a career in journalism. Her writing was direct and provocative, and in retaliation, Whites destroyed the offices and press of Free Speech, the paper for which she wrote.

Ida Wells moved to Chicago and continued to write and speak against lynching and for civil rights for African Americans. In 1906, she joined with W. E. B. DuBois and others to further the Niagara Movement, and she was one of two African American women to sign “the call” to form the NAACP in 1909. In 1930, she was one of the first Black women to run for public office in the United States. A year later, she passed away after a lifetime of activism.

The Daily Commercial and Evening Scimitar of Memphis Tenn., are owned by leading business men of that city, and yet in spite of the fact that there had been no white woman outraged by an Afro-American, and that Memphis possessed a thrifty law-abiding property-owning class of Afro-Americans the Commercial of May 17 [1892], under the head of “More Rapes, More Lynchings” gave utterance to the following:

The lynching of three Negro scoundrels reported in our dispatches from Anniston, Ala., for a brutal outrage committed upon a white woman will be a text for much comment on “Southern barbarism” by Northern newspapers; but we fancy it will hardly prove effective for campaign purposes among intelligent people. The frequency of these lynchings calls attention to the frequency of the crimes which cause lynching. The “Southern barbarism” which deserves the attention of all people North and South, is the barbarism which preys upon the weak and defenseless woman. Nothing but the most prompt, speedy and extreme punishment can hold in check the horrible and beastial propensities of the Negro race. There is a strange similarity about a number of cases of this character which have lately occurred.

In each case the crime was deliberately planned and perpetrated by several Negroes. They watched for an opportunity when the women were left without a protector. It was not a sudden yielding to a fit of passion, but the consummation of a devilish purpose which has been seeking and waiting for the opportunity….The swift punishment which invariably follows these horrible crimes doubtless acts as a deterring effect upon the Negroes in that immediate neighborhood for a short time. But the lesson is not widely learned nor long remembered…The facts of the crime appear to appeal more to the Negro’s lustful imagination that the facts of the punishment do to his fears. He sets aside all fear of death in any form when opportunity is found for gratification of his bestial desires….

…The generation of Negroes which have grown up since the Civil War have lost in large measure the traditional and wholesome awe of the white race which kept the Negroes in subjection, even when their masters were in the army, and their families left unprotected except by the slaves themselves. There is no longer a restraint upon the brute passion of the Negro.

What is to be done? The crime of rape is always horrible, but to the Southern man there is nothing which so fills the soul with horror, loathing and fury as the outraging of a white woman by a Negro. It is the race question in the ugliest, vilest, most dangerous aspect. The Negro as a political factor can be controlled. But neither laws nor lynchings can subdue his lusts. Sooner or later it will force a crisis…

In its issue of June 4, the Memphis Evening Scimitar gives the following excuse for lynch law:

Aside from the violation of white women by Negroes, which is the outcropping of a bestial perversion of instinct, the chief case of the trouble between the races in the South is the Negro’s lack of manners. In the state of slavery he learned politeness from association with white people, who took pains to teach him. Since the emancipation came and the tie of mutual interest and regard between master and servant was broken, the Negro has drifted away into a state which is neither freedom nor bondage. Lacking the proper inspiration of the one and the restraining force of the other he has taken up the idea that boorish insolence is independence and the exercise of a decent degree of breeding toward white people is identical to servile submission. In consequence of the prevalence of this notion there are many Negroes who use every opportunity to make themselves offensive, particularly when they think it can be done with impunity.

We have too many instances right here in Memphis to doubt this and our experience is not exceptional. The white people won’t stand for this sort of thing, and whether they be insulted as individuals or as a race, the response will be prompt and effectual. The bloody riot of 1866, in which so many Negroes perished, was brought principally by the outrageous conduct of the blacks toward the whites on the streets. It is also a remarkable and discouraging fact that the majority of such scoundrels are Negroes who have received educational advantages at the hands of white taxpayers. They have got just enough of learning to make them realize how hopelessly their race is behind the other in everything that makes a great people, and the attempt to “get even” by insolence, which is ever the resentment of inferiors. There are well-bred Negroes among us, and it is truly unfortunate that they should have to pay, even in part, the penalty of the offenses committed the baser sort, but this is the way of the world….

On March 9th, 1882, there were lynched in this same city [Memphis] three of the best specimens of young since-the-war Afro-American manhood. They were peaceful, law-abiding citizens and energetic business men.

They believed the problem was to be solved by eschewing politics and putting money in the purse. They owned a flourishing grocery business in a thickly populated suburb of Memphis, and a white man named Barrett had one on the opposite corner. After a personal difficulty which Barrett sought by going into the "People's Grocery" drawing a pistol and was thrashed by Calvin McDowell, he (Barrett) threatened to "clean them out." These men were a mile beyond the city limits and police protection; hearing that Barrett's crowd was coming to attack them Saturday night, they mustered forces and prepared to defend themselves against the attack.

When Barrett came he led a posse of officers, twelve in number, who afterward claimed to be hunting a man for whom they had a warrant. That twelve men in citizen's clothes should think it necessary to go in the night to hunt one man who had never before been arrested, or made any record as a criminal has never been explained. When they entered the back door the young men thought the threatened attack was on, and fired into them. Three of the officers were wounded, and when the defending party found it was officers of the law upon whom they had fired, they ceased and got away.

Thirty-one men were arrested and thrown in jail as "conspirators," although they all declared more than once they did not know they were firing on officers. Excitement was at fever heat until the morning papers, two days after, announced that the wounded deputy sheriffs were out of danger. This hindered rather than helped the plans of the whites. There was no law on the statute books which would execute an Afro-American for wounding a white man, but the "unwritten law" did. Three of these men, the president, the manager and clerk of the grocery"—the leaders of the conspiracy"—were secretly taken from jail and lynched in a shockingly brutal manner. "The Negroes are getting too independent," they say, "we must teach them a lesson."

What lesson? The lesson of subordination. "Kill the leaders and it will cow the Negro who dares to shoot a white man, even in self defense."

Although the race was wild over the outrage, the mockery of law and justice which alarmed men and locked them up in jails where they could be easily and safely reached by the mob—the Afro-American ministers, newspapers and leaders counselled obedience to the law which did not protect them.

Their counsel was heeded and not a hand was uplifted to resent the outrage; following the advice of the Free Speech, people left the city in great numbers.

Source: Reprinted in Wells-Barnett, Ida. On Lynchings. Introduction by Patricia Hill Collins. NY: Humanity Books, 2002. (Document 5.10.4)

It is a source of deep regret and sorrow to many good Christians in this country that the church puts forth so few and such feeble protests against lynching. As the attitude of many ministers on the question of slavery greatly discouraged the abolitionists before the war, so silence in the pulpit concerning the lynching of negroes to-day plunges many of the persecuted race into deep gloom and dark despair. Thousands of dollars are raised by our churches every year to send missionaries to Christianize the heathen in foreign lands, and this is proper and right. But in addition to this foreign missionary work, would it not be well for our churches to inaugurate a crusade against the barbarism at home, which converts hundreds of white women and children into savages every year, while it crushes the spirit, blights the hearth and breaks the hearts of hundreds of defenceless blacks? Not only do ministers fail, as a rule, to protest strongly against the hanging and burning of negroes, but some actually condone the crime without incurring the displeasure of their congregations or invoking the censure of the church. Although the church court which tried the preacher in Wilmington, Delaware, accused of inciting his community to riot and lynching by means of incendiary sermon, found him guilty of “unministerial and unchristian conduct,” of advocating mob murder and of thereby breaking down the public respect for the law, yet it simply admonished him to be “more careful in the future” and inflicted no punishment at all.

Such indifference to lynching on the part of the church recalls the experience of Abraham Lincoln, who refused to join a church in Springfield, Illinois, because only three out of twenty-two ministers in the whole city stood with him in his effort to free the slave. But, however unfortunate may have been the attitude of some churches on the question of slavery before the war, from the moment the shackles fell from the black man’s limbs to the present day, the American Church has been most kind and generous in its treatment of the backward and struggling race. Nothing but ignorance or malice could prompt one to disparage the efforts put forth by the churches in the negro’s behalf. But, in the face of so much lawlessness to-day, surely there is a role for the Church Militant to play. …

Source: North American Review, 178, (1904): pp. 853-68. (Document 5.10.6)

Letter from Eleanor Roosevelt to Walter White, Director of NAACP, March 10, 1936

President Roosevelt’s wife was supportive of the growing campaign to pass federal anti-lynching legislation. In this letter, she acknowledges President Roosevelt’s lack of support and suggests other strategies. FDR was concerned that pressing for a bill such as Costigan-Wagner would decrease the chances of his New Deal legislative agenda passing Congress.

THE WHITE HOUSE

WASHINGTON

March 19, 1936

My dear Mr. White:

Before I received your letter today I had been in to the President, talking to him about your letter enclosing that of the Attorney general. I told him that it seemed rather terrible that one could get nothing done and that I did not blame you in the least for feeling there was no interest in this very serious question. I asked him if there were any possibility of getting even one step taken, and he said the difficulty is that it is unconstitutional apparently for the Federal Government to step in in the lynching situation. The Government has only been allowed to do anything about kidnapping because of its interstate aspect, and even that has not as yet been appealed so they are not sure that it will be declared constitutional.

The President feels that lynching is a question of education in the states, rallying good citizens, and creating public opinion so that the localities themselves will wipe it out. However, if it were done by a Northerner, it will have an antagonistic effect. I will talk to him again about the Van Nuys resolution and will try to talk also to Senator Byrnes and get his point of view. I am deeply troubled about the whole situation as it seems to be a terrible thing to stand by and let it continue and feel that one cannot speak out as to his feeling. I think your next step would be to talk to the more prominent members of the Senate.

Very sincerely yours,

Eleanor Roosevelt

Source: www.assumption.edu/acad/ii/Academic/history/Hi113net/ERphotocopy.html. (Document 5.10.10)

During the 1920s, Langston Hughes was one of the most well-known and influential literary figures from the Harlem Renaissance. His poetry, plays, short stories and novels reflected the experiences of African Americans of his time. In response to the Scottsboro case he wrote a play and several poems, including “Scottsboro.”

Scottsboro

8 BLACK BOYS IN A SOUTHERN JAIL

WORLD, TURN PALE!

8 black boys and one white lie.

Is it much to die?

Is it much to die when immortal feet

March with you down Time's street,

When beyond steel bars sound the deathless drums

Like a mighty heart-beat as they come?

Who comes?

Christ,

Who fought alone

John Brown.

That mad mob

That tore the Bastile down

Stone by stone.

Moses.

Jeanne d'Arc.

Dessalines.

Nat Turner.

Fighters for the free.

Lenin with the flag blood red.

(Not dead! Not dead!

None of those is dead.)

Gandhi.

Sandino.

Evangelista, too.

To walk with you --

8 BLACK BOYS IN A SOUTHERN JAIL

WORLD, TURN PALE!

Source: Hughes, Langston. Scottsboro Limited, Four Poems and a Play in Verse. New York: Golden Stair Press, 1932. (Document 5.10.15)

www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/scottsboro/filmmore/ps_hughes.html

An extrajudicial act of violence and murder, typically involving the illegal hanging or killing of a person by a mob or group of individuals, often motivated by racial, religious, or social prejudice, and historically used as a tool of racial terror, intimidation, and social control, particularly against African Americans in the United States.

Racial terrorism refers to acts of violence, intimidation, or coercion perpetrated by individuals, groups, or institutions against people of a particular race or ethnic group, often motivated by prejudice, hatred, or supremacy, and aimed at instilling fear, exerting control, or asserting dominance over targeted populations. Racial terrorism can take various forms, including hate crimes, lynchings, racial profiling, and state-sponsored violence, and has been used throughout history to enforce racial segregation, uphold white supremacy, and suppress movements for racial equality and justice.

A system of racial segregation and discrimination that prevailed in the Southern United States from the late 19th century to the mid-20th century, characterized by laws, policies, and practices that enforced racial separation and promoted white supremacy, particularly in public facilities, accommodations, and institutions.

The principle of fairness, equity, and moral rightness in the application of laws, rules, or social practices, and the impartial treatment of individuals and groups, often associated with concepts of legal, social, and distributive justice, as well as with notions of rights, equality, and human dignity.

The obligation to accept responsibility for one's actions and to be answerable for the consequences.

An African American investigative journalist, educator, and civil rights activist, known for her pioneering work in documenting and exposing the widespread practice of lynching in the United States and for her advocacy for racial and gender equality.

The Scottsboro 9 refers to nine African American teenagers who were falsely accused of raping two white women on a train in Alabama in 1931. Their case became a symbol of racial injustice and sparked national and international outrage.

A formal request to a higher court to review and overturn a decision made by a lower court.

The legal principle that ensures fair and impartial treatment in legal proceedings, including the right to notice, a hearing, and a fair trial before being deprived of life, liberty, or property.

To deprive someone of the right to vote or participate in the political process, often through legal or administrative means.