Unit

Years: 1865–1876

Economy & Society

Historical Events, Movements, and Figures

When the Civil War ended in April 1865, the fate of the newly emancipated, or freed, African Americans was uncertain. The freedpeople themselves championed for their full rights as citizens. However, at first full citizenship seemed unlikely.

After Lincoln was assassinated, Vice President Andrew Johnson became president. Johnson began to lead the process of Reconstruction, or rebuilding society in the former Confederate states. Johnson was both conservative and stubborn. He did not consult Congress on his plan. He permitted the former Confederate states to re-enter the Union without changing who held power in the state. Believing that “white men alone must manage the South,” he made no arrangements for African Americans in former Confederate states to gain civil rights such as the right to vote.

Under Johnson’s plan for Reconstruction, many officials who had once served in the rebel government were reelected to the newly reconstructed state governments, including nine former Confederate congressmen. Worse yet, the new state governments of 1865-66 drafted a series of laws, known as the Black Codes, which severely limited the civil rights of the freedpeople. African Americans could be forced to work with little control over the hours and terms of their labor. They were also forbidden from serving on juries and had little access to the courts.

Republicans in Congress began to worry about these developments. If the freedpeople were denied their civil rights – if their contracts were not respected and they had no way to sue if they were not paid their wage – then was the Thirteenth Amendment abolishing slavery of any use? Didn’t the freedpeople remain enslaved in all but name? To many in Congress, the Confederates seemed to be winning in peace what they had lost in war.

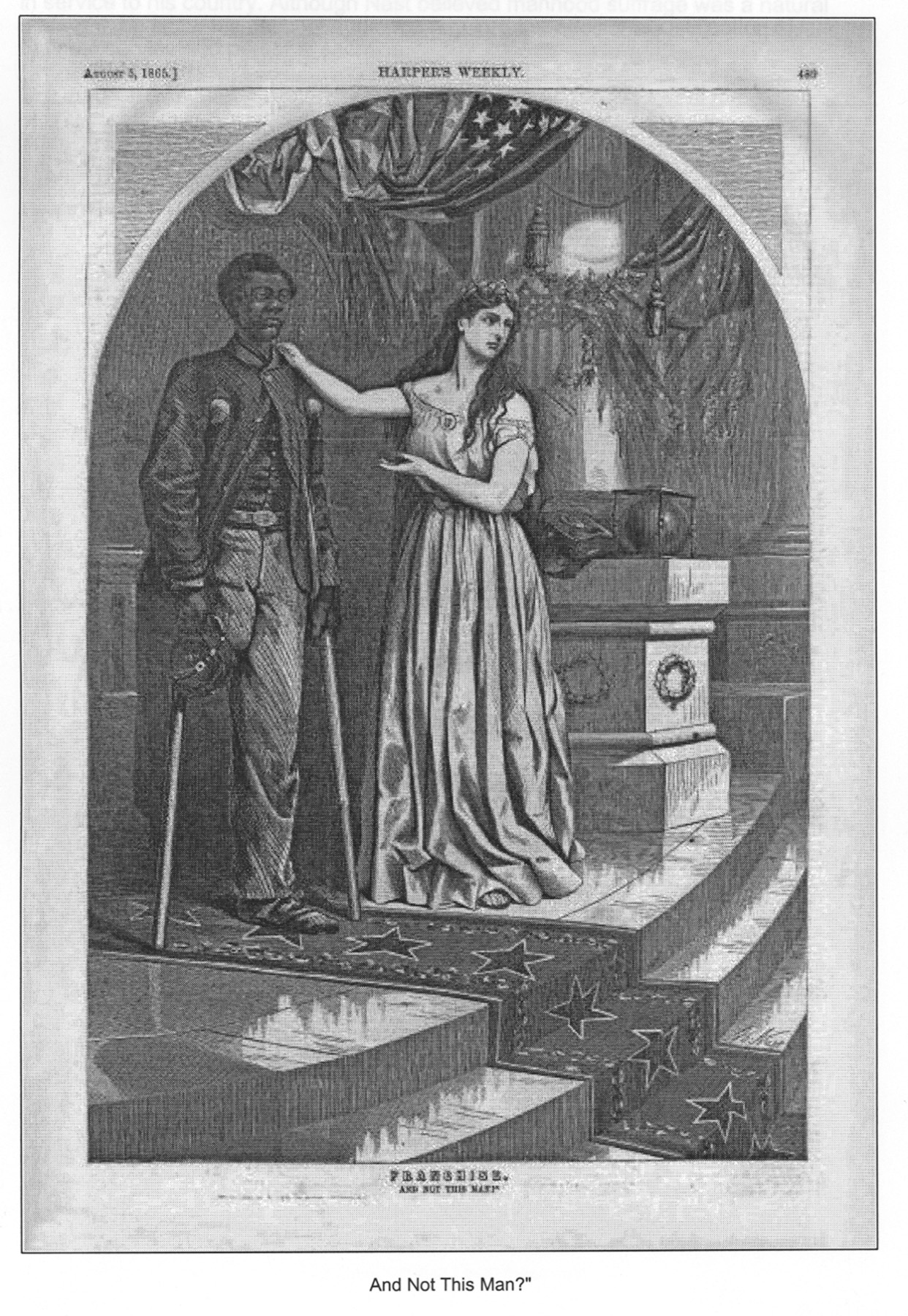

Some members of the Republican party, which was founded in the 1850s as a party opposed to the expansion of slavery, believed strongly in the rights of African Americans. Other Republicans had a growing belief that their grip on Congress was tenuous and that the enfranchisement of African Americans was the way to gain political support. Though different, these two beliefs brought Republicans together and led them to join forces with African Americans in taking measures to ensure male suffrage. Republicans joined forces with African Americans and, despite initial hesitation, took steps to ensure Black men’s right to vote. (Women gained the right to vote when the Nineteenth Amendment was ratified, or made into law, in 1920.)

Frederick Douglass, a great abolitionist and orator who was born into slavery and successfully sought his own freedom, wrote this article for a national magazine in 1866. Congress had already passed (over conservative President Andrew Johnson’s vetoes) two measures designed to help protect the civil rights of the freedspeople from the depredations of their former enslavers: the Civil Rights Bill of 1866, which wrote protections of African Americans’ civil rights into law; and the Freedmen’s Bureau Bill, which extended the life of a federal agency designed to oversee the reconstitution of the southern labor system. At the same time, Congress had drafted the 14th Amendment, which was designed to ensure the constitutionality of the Civil Rights Act of 1866. The 14th Amendment was not ratified until 1868. The 15th Amendment, guaranteeing voting rights to all men, regardless of race, color, or previous condition of servitude was not proposed to Congress until February 26, 1869.

_______________________________________________________________________________________

Whether the tremendous war so heroically fought and so victoriously ended shall pass into history a miserable failure, barren of permanent results; . . . or whether, on the other hand, we shall, as the rightful reward of victory over treason, have a solid nation, entirely delivered from all contradictions and social antagonisms, based upon loyalty, liberty, and equality, must be determined one way or the other by the present session of Congress.

The last session [of Congress] really did nothing which can be considered final as to these questions. The Civil Rights Bill and the Freedmen's Bureau Bill and the proposed constitutional amendments, with the amendment already adopted and recognized as the law of the land, do not reach the difficulty, and cannot, unless the whole structure of the government is changed from a government by States to something like a despotic central government, with power to control even the municipal regulations of States, and to make them conform to its own despotic will.

While there remains such an idea as the right of each State to control its own local affairs – an idea, by the way, more deeply rooted in the minds of men of all sections of the country than perhaps any one other political idea – no general assertion of human rights can be of any practical value. To change the character of the government at this point is neither possible nor desirable. All that is necessary to be done is to make the government consistent with itself, and render the rights of the States compatible with the sacred rights of human nature.

The arm of the Federal government is long, but it is far too short to protect the rights of individuals in the interior of distant States. They must have the power to protect themselves, or they will go unprotected, spite of all the laws the Federal government can put upon the national statute-book. . . .

The policy that emancipated and armed the negro – now seen to have been wise and proper by the dullest – was not certainly more sternly demanded than is now the policy of enfranchisement. If with the negro was success in war, and without him failure, so in peace it will be found that the nation must fall or flourish with the negro.

Fortunately, the Constitution of the United States knows no distinction between citizens on account of color. Neither does it know any difference between a citizen of a State and a citizen of the United States. Citizenship evidently includes all the rights of citizens, whether State or national. If the Constitution knows none, it is clearly no part of the duty of a Republican Congress now to institute one. The mistake of the last session was the attempt to do this very thing, by a renunciation of its power to secure political rights to any class of citizens, with the obvious purpose to allow the rebellious States to disfranchise, if they should see fit, their colored citizens. This unfortunate blunder must now be retrieved, and the emasculated citizenship given to the negro supplanted by that contemplated in the Constitution of the United States, which declares that the citizens of each State shall enjoy all the rights and immunities of citizens of the several States, so that a legal voter in any State shall be a legal voter in all the States.

Document 4.15.1: Excerpt from Frederick Douglass, “Reconstruction” (1866)

Frederick Douglass, a great abolitionist and orator who was born into slavery and successfully sought his own freedom, wrote this article for a national magazine in 1866. Congress had already passed (over conservative President Andrew Johnson’s vetoes) two measures designed to help protect the civil rights of the freedspeople from the depredations of their former enslavers: the Civil Rights Bill of 1866, which wrote protections of African Americans’ civil rights into law; and the Freedmen’s Bureau Bill, which extended the life of a federal agency designed to oversee the reconstitution of the southern labor system. At the same time, Congress had drafted the 14th Amendment, which was designed to ensure the constitutionality of the Civil Rights Act of 1866. The 14th Amendment was not ratified until 1868. The 15th Amendment, guaranteeing voting rights to all men, regardless of race, color, or previous condition of servitude was not proposed to Congress until February 26, 1869.

_______________________________________________________________________________________

Whether the tremendous war so heroically fought and so victoriously ended shall pass into history a miserable failure, barren of permanent results; . . . or whether, on the other hand, we shall, as the rightful reward of victory over treason, have a solid nation, entirely delivered from all contradictions and social antagonisms, based upon loyalty, liberty, and equality, must be determined one way or the other by the present session of Congress.

The last session [of Congress] really did nothing which can be considered final as to these questions. The Civil Rights Bill and the Freedmen's Bureau Bill and the proposed constitutional amendments, with the amendment already adopted and recognized as the law of the land, do not reach the difficulty, and cannot, unless the whole structure of the government is changed from a government by States to something like a despotic central government, with power to control even the municipal regulations of States, and to make them conform to its own despotic will.

While there remains such an idea as the right of each State to control its own local affairs – an idea, by the way, more deeply rooted in the minds of men of all sections of the country than perhaps any one other political idea – no general assertion of human rights can be of any practical value. To change the character of the government at this point is neither possible nor desirable. All that is necessary to be done is to make the government consistent with itself, and render the rights of the States compatible with the sacred rights of human nature.

The arm of the Federal government is long, but it is far too short to protect the rights of individuals in the interior of distant States. They must have the power to protect themselves, or they will go unprotected, spite of all the laws the Federal government can put upon the national statute-book. . . .

The policy that emancipated and armed the negro – now seen to have been wise and proper by the dullest – was not certainly more sternly demanded than is now the policy of enfranchisement. If with the negro was success in war, and without him failure, so in peace it will be found that the nation must fall or flourish with the negro.

Fortunately, the Constitution of the United States knows no distinction between citizens on account of color. Neither does it know any difference between a citizen of a State and a citizen of the United States. Citizenship evidently includes all the rights of citizens, whether State or national. If the Constitution knows none, it is clearly no part of the duty of a Republican Congress now to institute one. The mistake of the last session was the attempt to do this very thing, by a renunciation of its power to secure political rights to any class of citizens, with the obvious purpose to allow the rebellious States to disfranchise, if they should see fit, their colored citizens. This unfortunate blunder must now be retrieved, and the emasculated citizenship given to the negro supplanted by that contemplated in the Constitution of the United States, which declares that the citizens of each State shall enjoy all the rights and immunities of citizens of the several States, so that a legal voter in any State shall be a legal voter in all the States.

Document 4.15.1: Excerpt from Frederick Douglass, “Reconstruction” (1866)

Frederick Douglass, a great abolitionist and orator who was born into slavery and successfully sought his own freedom, wrote this article for a national magazine in 1866. Congress had already passed (over conservative President Andrew Johnson’s vetoes) two measures designed to help protect the civil rights of the freedspeople from the depredations of their former enslavers: the Civil Rights Bill of 1866, which wrote protections of African Americans’ civil rights into law; and the Freedmen’s Bureau Bill, which extended the life of a federal agency designed to oversee the reconstitution of the southern labor system. At the same time, Congress had drafted the 14th Amendment, which was designed to ensure the constitutionality of the Civil Rights Act of 1866. The 14th Amendment was not ratified until 1868. The 15th Amendment, guaranteeing voting rights to all men, regardless of race, color, or previous condition of servitude was not proposed to Congress until February 26, 1869.

_______________________________________________________________________________________

Whether the tremendous war so heroically fought and so victoriously ended shall pass into history a miserable failure, barren of permanent results; . . . or whether, on the other hand, we shall, as the rightful reward of victory over treason, have a solid nation, entirely delivered from all contradictions and social antagonisms, based upon loyalty, liberty, and equality, must be determined one way or the other by the present session of Congress.

The last session [of Congress] really did nothing which can be considered final as to these questions. The Civil Rights Bill and the Freedmen's Bureau Bill and the proposed constitutional amendments, with the amendment already adopted and recognized as the law of the land, do not reach the difficulty, and cannot, unless the whole structure of the government is changed from a government by States to something like a despotic central government, with power to control even the municipal regulations of States, and to make them conform to its own despotic will.

While there remains such an idea as the right of each State to control its own local affairs – an idea, by the way, more deeply rooted in the minds of men of all sections of the country than perhaps any one other political idea – no general assertion of human rights can be of any practical value. To change the character of the government at this point is neither possible nor desirable. All that is necessary to be done is to make the government consistent with itself, and render the rights of the States compatible with the sacred rights of human nature.

The arm of the Federal government is long, but it is far too short to protect the rights of individuals in the interior of distant States. They must have the power to protect themselves, or they will go unprotected, spite of all the laws the Federal government can put upon the national statute-book. . . .

The policy that emancipated and armed the negro – now seen to have been wise and proper by the dullest – was not certainly more sternly demanded than is now the policy of enfranchisement. If with the negro was success in war, and without him failure, so in peace it will be found that the nation must fall or flourish with the negro.

Fortunately, the Constitution of the United States knows no distinction between citizens on account of color. Neither does it know any difference between a citizen of a State and a citizen of the United States. Citizenship evidently includes all the rights of citizens, whether State or national. If the Constitution knows none, it is clearly no part of the duty of a Republican Congress now to institute one. The mistake of the last session was the attempt to do this very thing, by a renunciation of its power to secure political rights to any class of citizens, with the obvious purpose to allow the rebellious States to disfranchise, if they should see fit, their colored citizens. This unfortunate blunder must now be retrieved, and the emasculated citizenship given to the negro supplanted by that contemplated in the Constitution of the United States, which declares that the citizens of each State shall enjoy all the rights and immunities of citizens of the several States, so that a legal voter in any State shall be a legal voter in all the States.

Document 4.15.1: Excerpt from Frederick Douglass, “Reconstruction” (1866)

A simplified or exaggerated depiction of a person or thing, often used for comic effect or to emphasize certain features or traits.

To set free or liberate someone from slavery, bondage, or oppression.

The granting or restoration of the right to vote or participate in the political process, often after being disenfranchised or excluded.

An amendment to the United States Constitution, ratified in 1870, which prohibits the denial of voting rights based on race, color, or previous condition of servitude. This amendment extended suffrage to African American men and aimed to ensure their political participation and rights as citizens.

An amendment to the United States Constitution, ratified in 1868, which grants citizenship to all persons born or naturalized in the United States and guarantees equal protection under the law and due process of law to all citizens. This amendment played a crucial role in advancing civil rights and ensuring equal treatment for African Americans following the Civil War.

The branch of government responsible for making laws, often consisting of elected representatives or lawmakers who debate, draft, and enact legislation, and oversee the operation of government, typically organized into two houses or chambers, such as a bicameral legislature.

The period in American history following the Civil War, approximately from 1865 to 1877, where efforts were made to rebuild and transform the Southern states that had seceded from the Union. It aimed to address issues such as the integration of formerly enslaved African Americans into society.

A stereotype is a widely held but oversimplified and generalized belief or idea about a particular group of people, often based on assumptions, prejudices, or limited information, and lacking nuance or accuracy.

Suffrage refers to the right to vote in political elections, especially as exercised by citizens of a democracy. Suffrage movements advocate for the extension of voting rights to disenfranchised groups, such as women or minorities.

The Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, ratified in 1865, abolished slavery and involuntary servitude, except as punishment for a crime. It was a crucial step in ending institutionalized slavery in the United States following the Civil War and emancipating millions of enslaved individuals.