Unit

Years: 1846-1857

Culture & Community

Students should begin this lesson with a solid understanding of the Civil War’s causes and outcomes, and with some context for emancipation. For instance, knowledge of the Emancipation Proclamation and the experiences of Black Americans living under Union occupation during the Civil War will be a helpful foundation for this lesson. A basic understanding of the goals of Reconstruction will also be helpful, though this lesson may also be used as an introduction to Reconstruction’s opportunities and failures in the South.

Emancipation brought both opportunities and new obstacles to formerly enslaved Black Americans in the Reconstruction South. Black Americans worked hard and against many odds to reunite families torn apart by enslavement, and to create a new relationship with a government that now recognized their humanity. In some cases the freedpeople were supported in their efforts by the federal government; in others the government itself was part of the obstacle facing Black Americans during Reconstruction.

Introduction

The year 1865 was momentous. The Civil War ended and the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution was ratified, abolishing slavery across the entire United States. While some formerly enslaved people had experienced emancipation earlier–by escaping North to join the Union forces, through Union army rule in occupied zones in the South, or by way of Lincoln’s 1863 Emancipation Proclamation–the 13th Amendment made emancipation a reality for every Black person in the South.

Emancipation’s Opportunities and Obstacles

What did emancipation bring to the four million formerly enslaved people who were now free? For one, freedom brought opportunities to create new identities; many formerly enslaved people chose new names, rejecting those assigned to them by their former enslavers. Freedom also allowed some formerly enslaved people to reclaim power in public spaces through everyday, ordinary acts of defiance–by looking their former enslavers in the eye, or refusing to move for a White passerby on the street. All over the South, newly emancipated Black Americans experienced their freedom in diverse and powerful ways.

But freedom also brought challenges, and newly emancipated Black Americans faced many obstacles to living their lives truly free of oppression. One of the most emotionally wrenching challenges facing freedpeople at the war’s end was how to reunite and protect their families torn apart after generations of enslavement. Emancipation also changed the relationship between Black Americans and the U.S. government, and while the Freedmen’s Bureau was created to set up schools and help formerly enslaved people find housing and employment, the government also posed an obstacle to Black people seeking protection and recognition from American institutions that continued to exclude or discriminate against them. Indeed, the very institution created to assist formerly enslaved people in integrating into American society–the Freedmen’s Bureau–was known to apprentice orphaned Black children back to their former enslavers rather than reunite them with extended family.

Family Reunification

Formerly enslaved people faced a double-edged sword. Not only were many Southern Black families torn apart for economic gain by cruel or unfeeling enslavers, but White society used the separation of enslaved families–a tragedy that enslavers had created–to fuel a stereotype of Black Americans as caring little for family ties. This stereotype inhibited any careful and systematic attention to how to foster family reunification of freedpeople. Impoverished, lacking formal education, unheeded by those in power, emancipated Black Americans nonetheless did whatever was in their power to find and support not just immediate family, but extended and chosen family in their networks. They traveled hundreds of miles, wrote advertisements seeking lost relatives, and petitioned government agencies for assistance. Many couples also sought the legal recognition of their marriages, long forbidden under slavery. Marriages recognized by U.S. law brought not only respectability, but also rights over property and children.

While success was not universal, some families did manage to find each other and build new lives together.

Black Soldiers

Black soldiers who had fought for the Union Army faced particular frustrations. Many had enlisted under promises by the government to protect and support their families in the South. Yet the federal government, eager to lessen its wartime expenditures, quickly withdrew support and funding from Black communities. At the same time, Black soldiers were helpless to leave the army to help their families immediately after the war. The Union discharged soldiers in the order that they had enlisted; because Black soldiers were not allowed to enlist until years into the war, they were among the last to be released into civilian society. As was true with every promise freedom carried, the realities of life after emancipation often fell short of the ideals for which freedpeople had longed and fought.

Berlin, Ira, et. al., eds. Free at Last: A Documentary History of Slavery, Freedom, And the Civil War. New York: The New Press, 1992.

Berlin, Ira, Marc Favreau and Steven F. Miller, ed. Remembering Slavery: African Americans Talk about their Personal Experiences of Slavery and Freedom. New York: New Press, 1990.

Blassingame, John W., ed. Slave Testimony: Two Centuries of Letters, Speeches, Interviews, and Autobiographies. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1977.

Botkin, B.A., ed. Lay My Burden Down: A Folk History of Slavery. New York: Delta, 1994.

Cimbala, Paul A. “The Freedmen’s Bureau, the Freedmen, and Sherman’s Grant in Reconstruction Georgia, 1865-1867.” The Journal of Southern History, vol. 55, no. 4, 1989, pp. 597–632. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/2209042. Accessed 3 Aug. 2023.

Du Bois, W. E. B. (William Edward Burghardt), 1868-1963. The Souls of Black Folk; Essays and Sketches. Chicago, A. G. McClurg, 1903. New York: Johnson Reprint Corp., 1968.

“First Person Narratives of the American South 1860-1920.” University of North Carolina, https://docsouth.unc.edu/fpn/

Fleischman, Richard, et al. “THE U.S. FREEDMEN’S BUREAU IN POST-CIVIL WAR RECONSTRUCTION.” The Accounting Historians Journal, vol. 41, no. 2, 2014, pp. 75–109. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43487011. Accessed 3 Aug. 2023.

“Freedmen’s Bureau.” National Archives, October 28, 2021. https://www.archives.gov/research/african-americans/freedmens-bureau

“Freedmen’s Bureau Online.” Christine’s Genealogy Websites. http://freedmensbureau.com/

Fuke, Richard Paul. “Planters, Apprenticeship, and Forced Labor: The Black Family under Pressure in Post-Emancipation Maryland.” Agricultural History, vol. 62, no. 4, 1988, pp. 57–74. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3743375. Accessed 3 Aug. 2023.

We recommend taking care to use person-first language, such as the term “formerly enslaved people” instead of “former slaves,” when teaching about emancipation. “Formerly enslaved person” emphasizes the humanity of the person rather than reducing them only to a denigrated role in society. Similarly, “enslaver” is our recommended term over “master,” as “enslaver” names and holds the person accountable for their part in upholding the system of enslavement.

Emancipation and Reconstruction are complex historical events that invite critical analysis from our students, and we invite teachers to embrace the messy contradictions inherent in them–emancipation brought both opportunity and obstacles for Black Americans, and Reconstruction saw important political progress even as a simultaneous backlash brought new violence and repression. Two things can be true at once, and we encourage you to guide students in grappling with this difficult duality as a way to practice and hone their critical thinking skills.

Finally, some of the sources in this lesson contain the n-word, and we strongly recommend having some discussion with students about the historical context for its use, as well as its meaning today. Use discretion and provide content warnings about violent language before distributing sources that contain the n-word or other slurs.

The end of the Civil War and the passage of the 13th Amendment to the Constitution brought an end to enslavement across the United States. But emancipation–the freedom from bondage–had different effects on different people. For some formerly enslaved people, emancipation meant the freedom to define themselves outside of the system of enslavement by choosing a new name, enrolling in school, getting legally married, and reuniting with family. For others, emancipation brought continued racial discrimination, violence, and repression.

Emancipation came with its own set of opportunities, as well as new obstacles that Black Americans had to overcome to live truly free lives. The federal government created the Freedmen’s Bureau to assist formerly enslaved people in meeting these challenges and opportunities. The Freedmen’s Bureau supported Black Americans in finding their loved ones, set up public schools for Black children and adults, and distributed resources to formerly enslaved people who had few personal belongings. But the Freedmen’s Bureau and other government agencies–including the U.S. military–also limited the opportunities that Black people could pursue by enforcing exploitative sharecropping agreements, keeping Black soldiers from returning to their families, and failing to enshrine legal protections for Black Americans during the brief period of Reconstruction. For many formerly enslaved Black Americans, the promise of emancipation did not quite match its reality.

Select the activities and sources you would like to include in the student view and click “Launch Student View.”

It is highly recommended that you review the Teaching Tips and sources before selecting the activities to best meet the needs and readiness of your students. Activities may utilize resources or primary sources that contain historical expressions of racism, outdated language or racial slurs.

Begin by having students write down their own definition of the concept of freedom. Go around the room and have every student read out their definition, and take down the key concepts on the board.

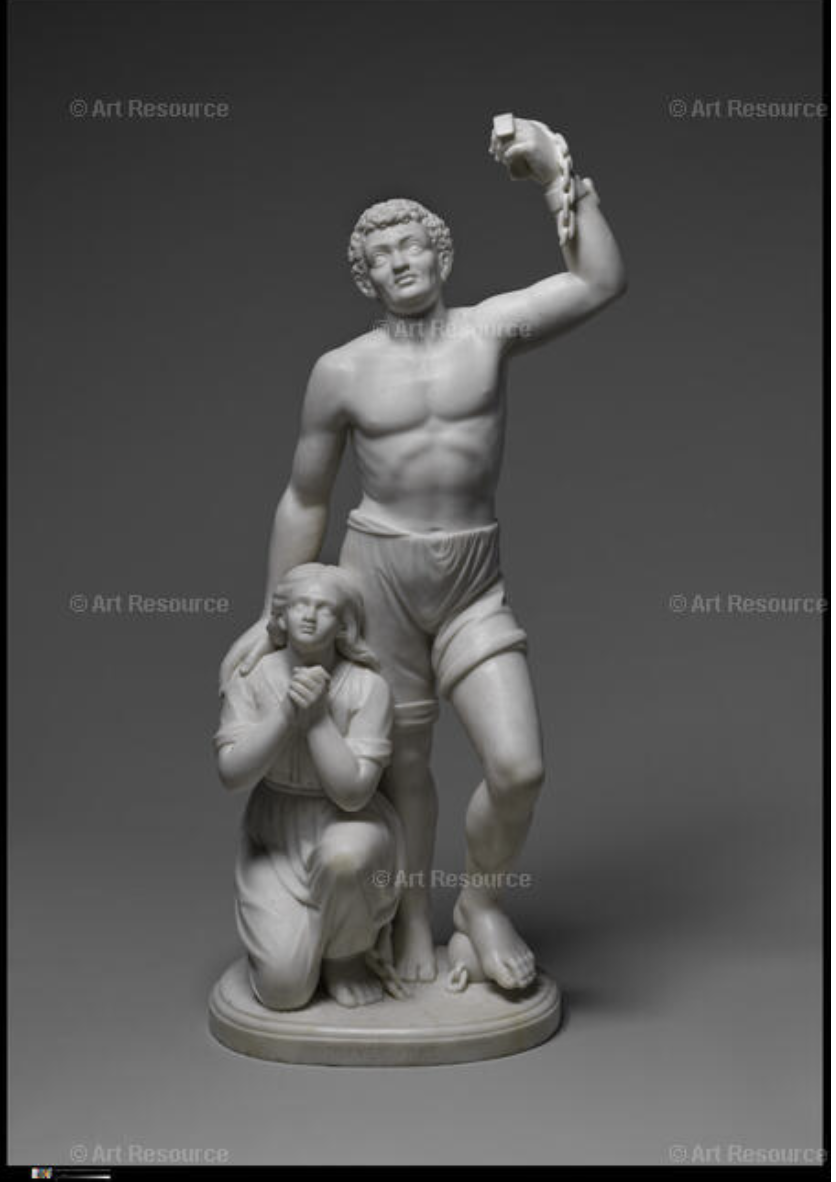

As a full class, show selected images of sculptures to students and have them write down 10 observations of the art work. Again, go around the room and have each student share one observation. Then repeat the process with a new image. Again, hear an observation from each student.

The selected image of the bust is a rear view. You may opt to share additional angles using the Metropolitan Museum of Art site. However, prior to utilizing additional sculpture images it is recommended you preview them as there is nudity in some of the images. As needed, provide a warning and reminder of expectations to students to ensure appropriate responses.

Note that the Metropolitan Museum of Art has numerous teaching resources to learn about the historical context and artists of both pieces, including related poetry and commentary that could deepen this activity or offer opportunities for learning extensions. Visit the online page for an exhibition on “Fictions of Emancipation: Carpeaux Recast” for resources.

Lead a class discussion using the following questions as prompts:

Divide students into small groups for a Jigsaw experience. Begin by giving each small group one of the following primary sources. Each primary source gives an account of a formerly enslaved person’s experience with emancipation. (Note that some of the sources use the n-word, and you should use discretion and provide a content warning for students before distributing them.)

Each group should read their assigned source and prepare a single slide with answers to the following questions:

Have groups share their slides with the class to share out. Conclude with a full class discussion on the following questions:

Excerpt from interview with former slave Felix Haywood, age 92, of San Antonio, Texas, “Like Freedom Was a Place” Felix Haywood, born into slavery in St. Hedwig, Texas, was one of thousands interviewed for the Slave Narrative Collection of the Federal Writers’ Project.

The end of the war, it come just like that—like you snap your fingers. . . . How did we know it! Hallelujah broke out—

Abe Lincoln freed the n*****

With the gun and the trigger;

And I ain't going to get whipped any more,

I got my ticket,

Leaving the thicket,

And I'm a-heading for the Golden Shore!

Soldiers, all of a sudden, was everywhere—coming in bunches, crossing and walking and riding, Everyone was a-singing. We was all walking on golden clouds. Hallelujah!

Union forever,

Hurrah, boys, hurrah!

Although I may be poor,

I'll never be a slave—

Shouting the battle cry of freedom.

Everybody went wild. We all felt like heroes, and nobody had made us that way but ourselves. We was free. Just like that, we was free. It didn’t seem to make the whites mad, either. They went right on giving us food just the same. Nobody took our homes away, but right off colored folks started on the move. They seemed to want to get closer to freedom, so they'd know what it was—like it was a place or a city. Me and my father stuck, stuck close as a lean tick to a sick kitten. The Gudlows started us out on a ranch. My father, he'd round up cattle—unbranded cattle—for the whites. They was cattle that they belonged to, all right; they had gone to find water 'long the San Antonio River and the Guadalupe. Then the whites gave me and my father some cattle for our own. My father had his own brand—7 B)—and we had a herd to start out with of seventy.

We knowed freedom was on us, but we didn’t know what was to come with it. We thought we was going to get rich like the white folks We thought we was going to be richer than the white folks, 'cause we was Stronger and knowed how to work, and the whites didn’t, and they didn’t have us to work for them any more. But it didn’t turn out that way. We soon found out that freedom could make folks proud, but it didn’t make 'em rich.

Did you ever stop to think that thinking don’t do any good when you do it too late! Well, that's how it was with us. If every mothers son of a black had thrown 'way his hoe and took up a gun to fight for his own freedom along with the Yankees, the war’d been over before it began. But we didn't do it. We couldn’ help stick to our masters. We couldn’t no more shoot 'em than we could fly. My father and me used to talk bout it. We decided we was too soft and freedom wasn’t going to be much to our good even if we had a education.

Source: reprinted in Botkin, B.A., ed. Lay My Burden Down: A Folk History of Slavery. Delta, 1989, 231. (Document 4.7.2)

Excerpt from interview with former slave Fred James, age 81, of Newberry, South Carolina, “When Christmas Came” Fred James, born into slavery, was one of thousands interviewed for the Slave Narrative Collection of the Federal Writers’ Project.

I ‘member when freedom come, Old Marse said, “You is all free, but you can work on and make this crop of corn and cotton; then I will divide up with you when Christmas comes.” They all worked, and when Christmas come, Marse told us we could get on and shuffle for ourselves, and he didn’t give us anything. We had to steal corn out of the cob. We prized the ears out between the cracks and took then home and parched them. We would have to eat on these for several days.

Source: reprinted in Botkin, B.A., ed. Lay My Burden Down: A Folk History of Slavery. Delta, 1989, 239. (Document 4.7.3)

Excerpt from interview with former slave Simon Phillips, age 90, of Birmingham, Alabama, “What’s Mine Is Mine” Simon Phillips, born into slavery in Hale County, Alabama in 1847, was one of thousands interviewed for the Slave Narrative Collection of the Federal Writers’ Project.

One day . . . a few n*****s was sticking sticks in the ground when the massa come up.

"What you n*****s doing!" he asked.

"We is staking off the land, Massa. The Yankees say half of it is ourn."

The massa never got mad. He just look calm-like.

"Listen, n*****s," he says, "what's mine is mine, and what's yours is yours You are just as free as I and the missus, but don't go fooling around my land. I've tried to be a good master to you. I have never been unfair. Now if you wants to stay, you are welcome to work for me. I'll pay you one-third the crops you raise. But if you wants to go, you sees the gate."

The massa never have no more trouble. Them n*****s just stays right there and works. Sometime they loaned the massa money when he was hard pushed. Most of 'em died on the old grounds.

Source: reprinted in Botkin, B.A., ed. Lay My Burden Down: A Folk History of Slavery. Delta, 1989, 239. (Document 4.7.4)

Excerpts from an interview between African American ministers and lay leaders and Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton and General William T. Sherman, Savannah, Georgia, January 12, 1865.

Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton and General William T. Sherman invited twenty African American leaders to meet with them to discuss the future of thousands of slaves now free as a result of General Sherman’s military advances. Garrison Frazier, a Baptist minister had been born in Granville County, North Carolina and was a slave until 1857, when he bought his freedom. The African Americans present chose him as their spokesman. The interview was reported in a New York newspaper the following month.

Second—State what you understand by Slavery and the freedom that was to be given by the President’s proclamation.

Answer—Slavery is, receiving by irresistible power the work of another man, and not by his consent. The freedom, as I understand it, promised by the proclamation, is taking us from under the yoke of bondage, and placing us where we could reap the fruit of our own labor, take care of ourselves and assist the Government in maintaining our freedom.

Third—State in what manner you think you can take care of yourselves, and how can you best assist the Government in maintaining your freedom.

Answer—The way we can best take care of ourselves is to have land, and turn it and till it by our own labor— that is, by the labor of the women and children and old men; and we can soon maintain ourselves and have something to spare. And to assist the Government, the young men should enlist in the service of the Government, and serve in such manner as they may be wanted…. We want to be placed on land until we are able to buy it and make it our own.

Fourth—State in what manner you would rather live—whether scattered among whites or in colonies by yourselves.

Answer—I would prefer to live by ourselves, for there is a prejudice against us in the South that will take years to get over; but I do not know that I can answer for my brethren….

Fifth—Do you think that there is intelligence enough among the slaves of the South to maintain themselves under the Government of the United States and the equal protection of its laws, and maintain good and peaceable relations among yourselves and with your neighbors?

Answer—I think there is sufficient intelligence among us to do so.

Sixth—State what is the feeling of the black population of the South toward the Government of the United States; what is the understanding in respect to the present war— its causes and object, and their disposition to aid either side. State fully your views.

Answer—I think you will find there are thousands that are willing to make any sacrifice to assist the Government of the United States, while there are also many that are not willing to take up arms. I do not suppose there are a dozen men that are opposed to the government, I understand, as to the war, that the South is the aggressor. President Lincoln was elected President by a majority of the United States, which guaranteed him the right of holding office and exercising that right over the whole United States. The South, without knowing what he would do, rebelled. The war was commenced by the Rebels before he came into office. The object of the war was not at first to bring the rebellious States back into the Union and their loyalty to the laws of the United States. Afterward, knowing the value set on the slaves by the Rebels, the President thought that his proclamation would stimulate them to lay down their arms and reduce them to obedience, and help to bring back the Rebel States; and their not doing so has made the freedom of the slaves a part of the war….

Seventh—State whether the sentiments you now express are those only of the colored people in the city; or do they extend to the colored population through the country? And what are your means of knowing the sentiments of those living in the country?

Answer—I think the sentiments are the same among the colored people of the State. My opinion is formed by personal communication in the course of my ministry, and also from the thousands that followed the Union army, leaving their homes and undergoing suffering. I did not think there would be so many; the number surpassed my expectation. . . .

Source: reprinted in Berlin, Ira, Barbara Fields, Steven Miller, Joseph P. Reidy and Leslie S. Rowland, ed. Free At Last: A Documentary History of Slavery, Freedom and the Civil War. New York: New Press, 1992. (Document 4.7.7)

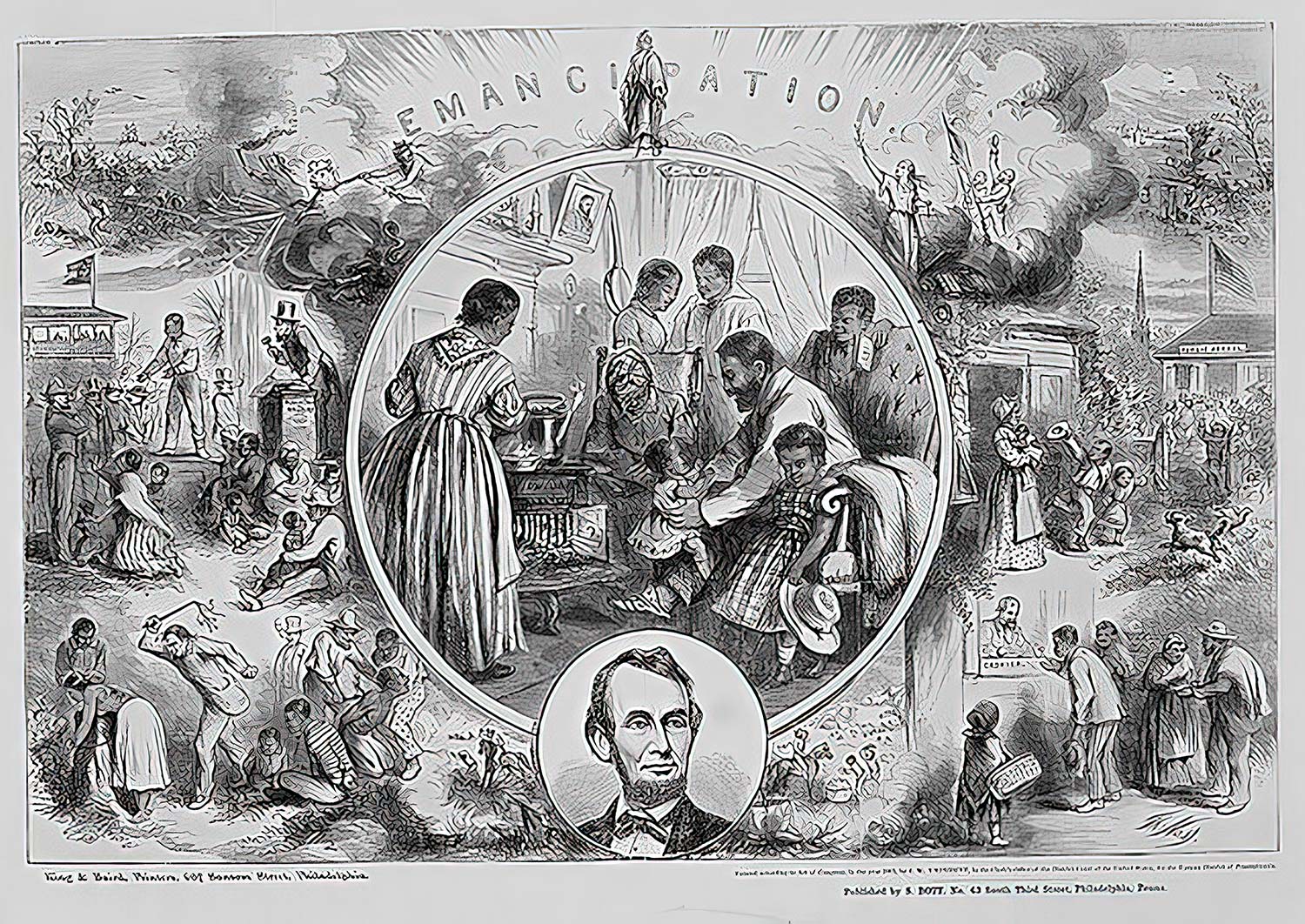

Display “Emancipation,” an 1865 political cartoon by Thomas Nast. Have students write down 3 observations, 2 interpretations, and 1 question they have about the cartoon. Have students share their responses in a think-pair-share formation.

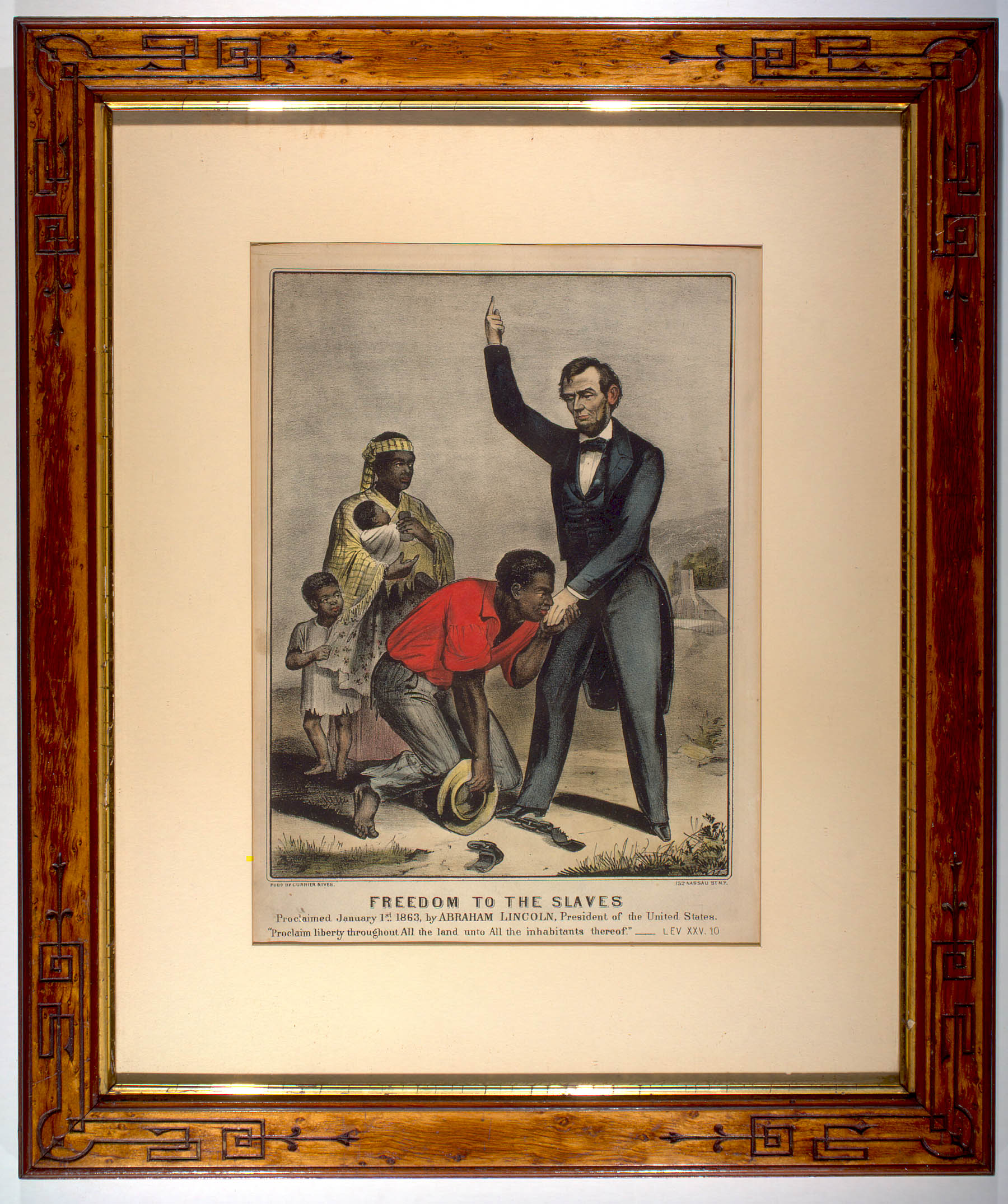

Then repeat the process with the political cartoon titled “Freedom to the Slaves” by Currier and Ives. Again, have them write down 3 observations, 2 interpretations, and 1 question they have about the cartoon and share their responses in a think-pair-share formation.

In small groups, instruct students to complete a compare and contrast diagram or Venn Diagram to note similarities and differences between the two prints. Students should focus on the meaning of the cartoons, as well as the artistic elements that help to convey that meaning (color, tone, captions, subjects, action, etc.). Lead a full class discussion to debrief.

Prior to using this with upper elementary students, consider developing further context through read-alouds. A recommended text is The Bell Rang by James E. Ransome.

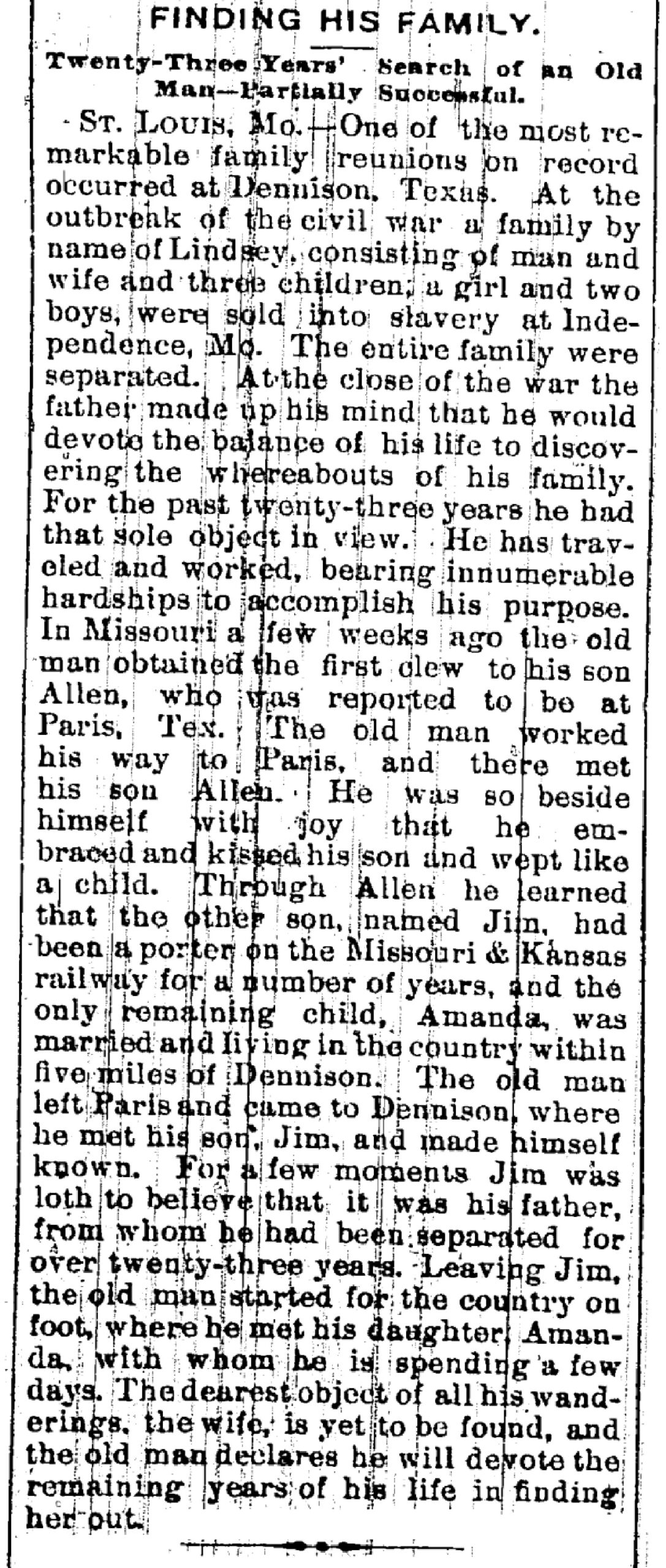

Place the following documents on posters around the classroom to participate in a Gallery Walk. Each document relates to the issue of Black families and reunification following emancipation.

Instruct students to walk around the room and answer the following three questions on each poster:

Then, divide students into small groups and give each small group just one of the posters. As a group, students should read through all the comments and prepare a short verbal presentation to the class summarizing the source’s main idea and any salient comments from the gallery walk. Take turns presenting the posters.

Advertisements seeking relatives, the Colored Tennesseean, Nashville, 1865.

Earlier in the nineteenth century, when huge plantations were created in the Deep South, slave owners broke up thousands of African American slave families to fill the need for labor. Once emancipated, freedpeople began to search for sons, daughters, husbands, wives, and parents. African American newspapers frequently carried advertisements such as the ones below.

Information Wanted of Caroline Dodson, who was sold from Nashville, Nov. 1st, 1862, by James Lumsden to Warwick (a trader then in human beings), who carried her to Atlanta, Georgia, and she was last heard of in the sale pen of Robert Clarke, (human trader in that place), from which she was sold. Any information of her whereabouts will be thankfully received and rewarded by her mother. Lucinda Lowery, Nashville.

-----------------------

$200 Reward. During the year 1849, Thomas Sample carried away from this city, as his slaves, our daughter, Polly, and son, Geo. Washington, to the State of Mississippi, and subsequently, to Texas, and when last heard from they were in Lagrange, Texas. We will give $100 each for them to any person who will assist them, or either of them, to get to Nashville, or get word to us of their whereabouts, if they are alive. Ben & Flora East.

-----------------------

Saml. Dove wishes to know of the whereabouts of his mother, Areno, his sisters Maria, Neziah, and Peggy, and his brother Edmond, who were owned by Geo. Dove, of Rockingham county, Shenandoah Valley, Va. Sold in Richmond, after which Saml. and Edmond were taken to Nashville, Tenn., by Joe Mick; Areno was left at the Eagle Tavern, Richmond. Respectfully yours, Saml. Dove, Utica, New York!

Source: Reprinted in Smith, John David. Black Voices from Reconstruction: 1865-1877. Brookfield, CT: The Millbrook Press, 1996, 51-2. (Document 4.7.9)

Letter from the Wife of a Michigan Black Soldier to the Secretary of War, May 11, 1865.

Detroit May 11 1865

Dear sir I have taken the Liberty to write you afew lines which I am compelled to do I am colored it is true but I have feeling as well as white person and why is it the colored soldiers letters cant pass backward and fowards as well as the white ones Mr Stanton Dear sir I think it very hard We cant get any letters and I wish would please look in this matter and have things arranged so we can hear from our Husband if we cant see them I have not heard from my Husband in three months John Bailey is my husband he was Drum major of the 100th united States Colored Troops he went from Detroit he is the man Senator Howard wrote to you about last summer and tried to get afurlogh for him Then he was sick I have hurd through others he was very sick and since that I have heard he was dead if he is living I wish you would please grant him afurlogh to come home he was promised one when he went away and he has been gone over a year and I do wish you would be so kind as to let him come home if he is living I wish you would look oar your Books and see if he is alive I dont know who to write to only you President Lincoln is gone and he was our best friend and now we look to you and I hope God will wach over and protect you through this war

Please write me as soon as you get this Direct to Mrs. Lucy Bailey 190 Congress Street 190

Source: reprinted in Berlin, Ira, Barbara Fields, Steven Miller, Joseph P. Reidy and Leslie S. Rowland, ed. Free At Last: A Documentary History of Slavery, Freedom and the Civil War. New York: New Press, 1992. (Document 4.7.10)

Report from army chaplain A.B. Randall, attached to a regiment of Black soldiers in Little Rock, Arkansas, 1865

Denied legal marriage under slavery, many freedpeople quickly sought to legalize longstanding relationships. Clergymen—particularly the Union army chaplains present throughout much of the South—found themselves in great demand. A.B. Randall was an army chaplain with a Black regiment in Arkansas.

Little Rock Ark Feb 28th 1865

Weddings, just now, are very popular, and abundant among the Colored People. They have just learned of the Special Order No. 15 of Gen. Thomas by which, they may not only be lawfully married, but have their Marriage Certificates Recorded; in a book furnished by the Government. This is most desirable; and the order, was very opportune as these people were constantly losing their certificates. Those who were captured from the “Chepewa” at Ivy’s Ford on the 17th of January, by Col. Brooks, had their Marriage Certificates taken from them and destroyed; and then were roundly cursed for having such papers in their possession. I have married, during the month at this Post, Twenty five couples, mostly those who have families and have been living together for years. I try to dissuade single men who are soldiers from marrying until their time of enlistment is out, as that course seems to me to be most judicious.

The Colored People here, generally consider, this war not only; their exodus from bondage, but the road to Responsibility; Competency; and honorable Citizenship—God grant that their hopes and expectations may be fully realized. Most Respectfully

A.B. Randall

Source: Reprinted in Berlin, Ira and Leslie S. Rowland, eds. Families and Freedom: A Documentary History of African American Kinship in the Civil War Era. New York: New Press, 1997. 163. (Document 4.12.1)

Freedwoman’s letter to her husband who had been seeking her. April 7, 1866

Across the former slave states, freedpeople went about the monumental task of reuniting families, which had been torn apart by slavery. Phillip Grey, a freedman of Virginia, found his wife, Willie Ann, and their daughter in Kentucky. However, after their involuntary separation, Willie Ann had remarried and had three additional children by her second husband. He died serving in the Union army. To Phillip Grey, she wrote:

Salvisa KY April 7th 1866

Dear Husband,

I seat myself this morning to write you a few lines to let you know that I received your letter the 5 of this month and was very glad to hear from you and to hear that you was well. This leaves us all well at present and I hope these lines may find you still in good health. You wish me to come to Virginia. I had much rather that you would come after me but if you cannot make it convenient you will have to make some arrangements for me and the family. I have 3 little fatherless girls. My husband went off under Burbridges command and was killed at Richmond, VA. If you can pay my passage through there I will come the first of May. I have nothing much to sell as I have had my things all burnt so you know that what I would sell would not bring much. You must not think my family too large and get out of heart for if you love me you will love my children and you will have to promise me that you will provide for them all as well as if they were your own. I heard that you spoke of coming for Maria but was not coming for me. I know that I have lived with you and loved you then and I love you still. Every time I hear from you my love grows stronger. I was very low spirited when I heard that you was not coming for me. My heart sank within me in an instant. You will have to write and give me directions how to come. I want when I start to come the quickest way that I can come. I do not want to be detained on the road. If I was the expense would be high and I would rather not have much expense on the road. Give me directions which is the nearest way so that I will not have any trouble after I start from here. Phebe wishes to know what has become of Lawrence. She heard that he was married but did not know whether it was so or not. Maria sends her love to you but seems to be low spirited for fear that you will come for her and not for me. John Phebe’s son says he would like to see his father but does not care about leaving his mother who has taken care of him up to this time. He thinks that she needs help and if he loves her he will give her help. I will close now by requesting you write as soon as you receive this so no more at present but remain your true (I hope to be with you soon) wife.

Willie Ann. Grey

To Phillip Grey

Aunt Lucinda sends her love to you. She has lost her husband and one daughter, Betsy. She left 2 little children. The rest are all well at present. Pheby’s Mary was sold away from her. She heard from her the other day. She was well.

Direct your letters to Mrs. Mollie Roche Salvisa KY

Source: Reprinted in Berlin, Ira and Leslie S. Rowland, eds. Families and Freedom: A Documentary History of African American Kinship in the Civil War Era. New York: New Press, 1997. 173. (Document 4.12.4)

Place students into pairs, and give each pair George Cole’s description of mutiny by his all-Black brigade in the Union army. Explain that the Union army released soldiers in the same order that they enlisted, and because Black soldiers weren’t permitted to enlist until later in the Civil War, they were kept in the army after fighting ended and sent to Texas (and elsewhere) rather than home to their newly emancipated families. This document describes the reaction and defiance of some Black soldiers, who wanted to return to their families as soon as possible.

Students should use the OPCVL document analysis protocol to analyze the source, and should prepare a short oral presentation to the class to summarize their analyses. After each pair shares their analysis, ask the class the following questions and facilitate a closing discussion:

Excerpt from report by George W. Cole of mutiny by his Black brigade, June 1865

Union regiments were demobilized in the order that they had been organized. As a result, Black regiments, largely recruited after 1863, were among the last to be sent home. Some Black soldiers were ordered to the Rio Grande border to fight French-backed forces that had taken control of Mexico.

[Brazos Santiago, TX June 1865]

The majority of the 1st and 2nd Regiment USC[olored] Cavalry are residents of Portsmouth and Norfolk and vicinity, and the 2 USC[olored] Cavalry, having met their families and children (nearly 1000 as I am informed), they were unwilling to leave them unprovided with money or rations. Consequently, they became excited and decidedly insubordinate. At which juncture Major Dollard Comd’g instead of being with his men on shore to rule and prevent outrage, retired to the Cabin of the Steamer and some time after called the Line Officers away from their Commands, probably for consultation thus leaving the men on shore unrestrained by their presence.

During the excitement, some (20) twenty Men deserted and left with their families, but in a few hours order was restored and the leaders of the Mutiny I took from the Boat—placed in irons, and have them in custody.

All the men appearing contented before seeing their families, and even afterward promptly obeyed all orders in arresting their comrades, but were enraged at the threat of using white troops to coerce them, as was offered by Major Dollard 2nd USC[olored] C[avalry].

I found the same feeling of discontent and insubordination in the 1st Regiment USC[olored] Cavalry. Many were wishing to see their families and being unable to make any provision for their support from not having been paid and rations having been stopped to soldiers and their wives.—

Major Brown, Comd’g 1st USC[olored] C[avalry] while this state of affairs prevailed left his command and was absent at Norfolk all night leaving his arms on the dock at Fort Monroe, and his Troops in charge of his subordinate officers who found it necessary to shoot (not fatally) one man and turn over to me six more whom I ironed.

With the exception of Major Brown. . . and Major Dollard. . , the officers of the Brigade both Staff and Regimental were all prompt and dutiful, and for their close attention to duty, and sober, earnest labor in the prompt and thorough embarkation of this Command (no boat being detained an hour) they merit my warmest thanks, not one being behind time or neglecting an order a course of conduct which if pursued by their superiors would I am convinced have prevented any disturbance whatever, for every man left Camp as cheerfully as ever before.

I should have placed both Major Brown and Major Dollard in arrest but for the apparent encouragement to the insubordinate enlisted men—

I have mentioned the condition of the families, etc. not as an excuse for the conduct of the men but showing the cause of the excitement and the stupidity of permitting them the inflammatory stimulus of free intercourse with the howling multitude—

We arrived at Mobile Bay the 23rd instead of having had a smooth voyage of seven (7) days where (Fort Morgan) we found orders to proceed to Brazos Santiago, Texas.

A report of the voyage from Mobile Bay to Brazos Texas will be forwarded as soon as practicable. I remain Very Respectfully Your Obedient Servant

George W. Cole

Source: Reprinted in Berlin, Ira and Leslie S. Rowland, eds. Families and Freedom: A Documentary History of African American Kinship in the Civil War Era. New York: New Press, 1997. 127. (Document 4.12.3)

Have students independently read Black Past’s summary of the Freedmen’s Bureau (external resource). As they read, students should take notes on new information. Lead a brief opening discussion using the following questions to check for understanding and activate prior knowledge:

Divide students into two groups. One group is assigned to argue that the U.S. government was helpful to formerly enslaved people after emancipation, and the other is assigned to argue that the U.S. government was more harmful than helpful. Give all students access to the following primary and secondary sources for their research:

Students work in their team to prepare an opening statement and central argument. They should support their claims with evidence from the sources and additional research as needed. Run the debate with the following schedule:

Students reflect on the debate by writing a paragraph in response to one of the following questions:

Excerpts from requests for interventions sent to Freedman’s Bureau, June 1865

Army Chaplain William A. Green and several missionaries requested help when a reduction in rations on Roanoke Island created a crisis.

Roanoke Island. N.C. June 5” 1865

General In behalf of suffering humanity which it is not within our power to relieve, we appeal to you trusting that the necessity of the case may be sufficient reason for addressing you personally and directly

There are about thirty five hundred blacks upon this island, the larger part of whom are dependents of the following classes, viz. Aged and Infirm, Orphan children and soldiers wives and families. Of these about twenty seven hundred have (including children) drawn rations from the Government, and by this assistance and the exertions of benevolent Societies they have been cared for, though not without extreme suffering in many instances up to the present time.

Those who are able to work have proved themselves industrious and would support themselves, had they the opportunity to do so, under favorable circumstances. The able bodied males with few exceptions are in the army, and there are not many families on the Island that have not furnished a father, husband or son, and in numerous instances, two and three members to swell the ranks of our army. And these left their families and enlisted with the assurance from the Government that their families should be cared for, and supported in their absence.

The issue of rations has been reduced, so that only about fifteen hundred now receive any subsistence from the Government. The acre of ground allotted to each family has been cleared and tilled, to the best of their ability – but this has only produced a very small part of what has been, and is required for family consumption. . . .

There are numerous cases of orphan children who have been taken in and afforded shelter while subsistence was furnished, who are now cast off because they have nothing to eat.

There are many who are sick and disabled whose ration has been cut off, and these instances are not isolated, but oft recurring and numerous. It is a daily occurrence to see scores of women and children crying for bread, whose husbands, sons and fathers are in the army today, and because these things are fully known, and understood by those whose duty it is to attend to, and remedy them and disregarded by them. we appeal to a Source more remote and out of the ordinary channel.

We do this with a feeling that the emergency demands immediate action to prevent suffering which justice, humanity, and every principle of christianity forbids.

With the hope of immediate investigation which Shall bring with it a Speedy relief, We remain Your Obt Ser’ts [Obedient Servants]

Wm A Green Susan Odell

Caroline A Green Mrs. R.S.D. Holboro

Amasa Walker Stevens Ella Roper

Mrs. S.P. Freeman E.P. Bennett

Esther A. Williams Kate L. Freeman

___________________________________________________________________

Black soldiers wrote to the commissioner of the bureau seeking assistance for their families who lived on Roanoke Island.

City Point Va. May or June 1865

General

We the soldiers of the 36 U.S. Col[ored] Regiment humbly petition to you to alter the Affairs at Roanoke Island. We have served in the US Army faithfully and done our duty to our Country, for which we thank God (that we had the opportunity) but at the same time our family’s are suffering at Roanoke Island N.C.

1st When we were enlisted in the service we were promised that our wives and family’s should receive rations from the government. The rations for our wives and families have been (and are now cut down) to one half the regular ration. Consequently three or four days out of every ten days, they have nothing to eat. At the same time our rations are stolen from the ration house by Mr. Streeter the Assistant Superintendent at the Island (and others) and sold while our families are suffering for something to eat.

2nd Mr. Streeter the Assistant Superintendent of Negro Affairs at Roanoke Island is a througher Cooper head* a man who says that he is no part of a Abolitionist, takes no care of the colored people and has no Sympathy with the colored people. A man who kicks our wives and children out of the ration house or commissary, he takes no notice of their actual suffering and sells the rations and allows it to be sold, and our families suffer for something to eat.

3rd Captain James the Suptn in charge has been told of these facts and has taken no notice of them. So has Colonel Lahman the Commander in charge of Roanoke, but no notice is taken of it, because it comes from Contrabands or Freedmen. The cause of much suffering is that Captain James has not paid the Colored people for their work for near a year and at the same time cuts the rations off to one half so the people have neither provisions or money to buy it with. There are men on the Island that have been wounded at Dutch Gap Canal, working there, and some discharged soldiers, men that were wounded in the service of the U.S. Army, and returned home to Roanoke that cannot get any rations and are not able to work, some soldiers are sick in Hospitals that have never been paid a cent and their families are suffering and their children going crying without anything to eat.

4th Our families have no protection. The white soldiers break into our houses act as they please, steal our chickens, rob our gardens and if any one defends their selves against them they are taken to the guard house for it. So our families have no protection when Mr. Streeter is here to protect them and will not do it.

5th General, we the soldiers of the 36 U.S. Colored Troops having familys at Roanoke Island humbly petition you to favor us by removing Mr. Streeter the present Assistant Superintendent at Roanoke Island under Captain James.

General, perhaps you think the Statements against Mr. Streeter too strong, but we can prove them.

General, order chaplain Green to Washington to report the true state of things at Roanoke Island, with Mr. Holland Streeter and he can prove the facts. and there are plenty of white men here that can prove them also, and many more thing’s not mentioned. Signed in behalf of humanity

Richard Etheredge

William Benson

Source: Reprinted in Berlin, Ira and Leslie S. Howland, eds. Families and Freedom: A Documentary History of African American Kinship in the Civil War Era. New York: New Press, 1997. 125. (Document 4.12.2)

Excerpt from report by George W. Cole of mutiny by his Black brigade, June 1865

Union regiments were demobilized in the order that they had been organized. As a result, Black regiments, largely recruited after 1863, were among the last to be sent home. Some Black soldiers were ordered to the Rio Grande border to fight French-backed forces that had taken control of Mexico.

[Brazos Santiago, TX June 1865]

The majority of the 1st and 2nd Regiment USC[olored] Cavalry are residents of Portsmouth and Norfolk and vicinity, and the 2 USC[olored] Cavalry, having met their families and children (nearly 1000 as I am informed), they were unwilling to leave them unprovided with money or rations. Consequently, they became excited and decidedly insubordinate. At which juncture Major Dollard Comd’g instead of being with his men on shore to rule and prevent outrage, retired to the Cabin of the Steamer and some time after called the Line Officers away from their Commands, probably for consultation thus leaving the men on shore unrestrained by their presence.

During the excitement, some (20) twenty Men deserted and left with their families, but in a few hours order was restored and the leaders of the Mutiny I took from the Boat—placed in irons, and have them in custody.

All the men appearing contented before seeing their families, and even afterward promptly obeyed all orders in arresting their comrades, but were enraged at the threat of using white troops to coerce them, as was offered by Major Dollard 2nd USC[olored] C[avalry].

I found the same feeling of discontent and insubordination in the 1st Regiment USC[olored] Cavalry. Many were wishing to see their families and being unable to make any provision for their support from not having been paid and rations having been stopped to soldiers and their wives.—

Major Brown, Comd’g 1st USC[olored] C[avalry] while this state of affairs prevailed left his command and was absent at Norfolk all night leaving his arms on the dock at Fort Monroe, and his Troops in charge of his subordinate officers who found it necessary to shoot (not fatally) one man and turn over to me six more whom I ironed.

With the exception of Major Brown. . . and Major Dollard. . , the officers of the Brigade both Staff and Regimental were all prompt and dutiful, and for their close attention to duty, and sober, earnest labor in the prompt and thorough embarkation of this Command (no boat being detained an hour) they merit my warmest thanks, not one being behind time or neglecting an order a course of conduct which if pursued by their superiors would I am convinced have prevented any disturbance whatever, for every man left Camp as cheerfully as ever before.

I should have placed both Major Brown and Major Dollard in arrest but for the apparent encouragement to the insubordinate enlisted men—

I have mentioned the condition of the families, etc. not as an excuse for the conduct of the men but showing the cause of the excitement and the stupidity of permitting them the inflammatory stimulus of free intercourse with the howling multitude—

We arrived at Mobile Bay the 23rd instead of having had a smooth voyage of seven (7) days where (Fort Morgan) we found orders to proceed to Brazos Santiago, Texas.

A report of the voyage from Mobile Bay to Brazos Texas will be forwarded as soon as practicable. I remain Very Respectfully Your Obedient Servant

George W. Cole

Source: Reprinted in Berlin, Ira and Leslie S. Rowland, eds. Families and Freedom: A Documentary History of African American Kinship in the Civil War Era. New York: New Press, 1997. 127. (Document 4.12.3)

Report from army chaplain A.B. Randall, attached to a regiment of Black soldiers in Little Rock, Arkansas, 1865

Denied legal marriage under slavery, many freedpeople quickly sought to legalize longstanding relationships. Clergymen—particularly the Union army chaplains present throughout much of the South—found themselves in great demand. A.B. Randall was an army chaplain with a Black regiment in Arkansas.

Little Rock Ark Feb 28th 1865

Weddings, just now, are very popular, and abundant among the Colored People. They have just learned of the Special Order No. 15 of Gen. Thomas by which, they may not only be lawfully married, but have their Marriage Certificates Recorded; in a book furnished by the Government. This is most desirable; and the order, was very opportune as these people were constantly losing their certificates. Those who were captured from the “Chepewa” at Ivy’s Ford on the 17th of January, by Col. Brooks, had their Marriage Certificates taken from them and destroyed; and then were roundly cursed for having such papers in their possession. I have married, during the month at this Post, Twenty five couples, mostly those who have families and have been living together for years. I try to dissuade single men who are soldiers from marrying until their time of enlistment is out, as that course seems to me to be most judicious.

The Colored People here, generally consider, this war not only; their exodus from bondage, but the road to Responsibility; Competency; and honorable Citizenship—God grant that their hopes and expectations may be fully realized. Most Respectfully

A.B. Randall

Source: Reprinted in Berlin, Ira and Leslie S. Rowland, eds. Families and Freedom: A Documentary History of African American Kinship in the Civil War Era. New York: New Press, 1997. 163. (Document 4.12.1)

A grandmother’s letter to the chief agent of the Freedman’s Bureau seeking aid in gaining the custody of her grandson, along with the endorsement letter of an agent of the Bureau, January 1867

Freedpeople struggled not only to reunite families sold apart, but to keep intact the family they had. The Freedman’s Bureau often placed orphaned African American children as apprentices, sometimes with their former owners. Extended family members fought for custody both to stabilize families but also because children were a valuable source of labor.

Clinton, LA. Jary 10th 1867

Honorable Sir

I am the mother of a woman Dina who is now dead. My Daughter Dina had a child boy by the name of Porter. I am a Colored Woman former slave of a Mr. Sandy Spears of the parish of East Feliciana La. Said Porter is now about Eleven years of age. Mr. Spears has had the little boy Porter bound over to him so I am told by the agent of the Freedmen in this parish. I was not informed of this fact until after the matter of binding was consummated. I do not wish to wrongfully interfere with the arrangement of those who are endeavoring to properly control us black people. I feel confidently they are doing the best they can for us and our present condition—but I am the Grandmother of Porter—his Father Andrew is now and has been for some time a soldier in the Army of the U.S. He is, I am told, somewhere in California. I do not know only that he is not here to see the interest of his child. I am not by any means satisfied with the present arrangement made for my Grand Child Porter. Mr. Spears I have known for many years. I will say nothing of his faults, but I have the means of educating my Grand Child of doing a good part by him. His Uncle who has been lately discharged from the Army of the U.S.—Humphrey Cold who now resides in this parish is fully able to assist me in maintaining my Grand child Porter. We want him. We do not think Mr. Spears a suitable person to control this boy. Mr. Spears is very old and infirm. He is and has been for many years addicted to the use of ardent spirits. This fact I do not like to mention but truth requires me to speak. Now is there no chance to get my little boy. The agent of this place will not listen to me, and I am required to call on you or I must let my Grand Child go which greatly grieves me. Will you be so kind after my statement to write to Elizabeth Collins f[ree] w[oman of] c[olor], Clinton La., the Step mother of Porter, and advise her what I shall do to obtain my little Grand Child. Please answer this letter and you will greatly oblige. Truly yours a poor old black woman.

Cynthia NicKols

f.w.c.

[free woman of color]

[Endorsement by Lt. James DeGrey, Freedman’s Bureau agent] Parish East Feliciana La. Clinton La January 29th 1867…Sandy Spears is as stated old, but not infirm. He is addicted to ardent Spirits, but not more so than the most of men in the Parish. The boy Porter is ten (10) years of age. He (Spears) raised him from a child. My belief is, the old lady wants the boy because he is now able to do some work. The binding of our children seems to the freemen like putting them back into Slavery. In every case where I have bound children, thus far some Grand Mother or Fortieth cousin has come to have them released.

Source: Reprinted in Berlin, Ira and Leslie S. Rowland, eds. Families and Freedom: A Documentary History of African American Kinship in the Civil War Era. New York: New Press, 1997. 240. (Document 4.12.5)

Excerpts from a Protest Memorial sent to President Andrew Johnson, 1865.

On June 10, 1865, more than 3,000 African Americans gathered in the First Baptist Church of Richmond, Virginia, to listen as a “protest memorial” that had been sent to President Andrew Johnson on their behalf, was read aloud:

Mr. President,

We have been appointed a committee by a public meeting of the colored people of Richmond, Va., to make known . . . the wrongs, as we conceive them to be, by which we are sorely oppressed. . . .

We represent a population of more than 20,000 colored people, including Richmond and Manchester, . . . more than 6,000 of our people are members . . . of Christian churches, and nearly our whole population . . . attend divine services. Among us there are at least 2,000 men who are worth $200 to $500; 200 who have property valued at from $1,000 to $5,000, and a number who are worth from $5,000 to $20,000. . . .

None of our people are in the alms-house, and when we were slaves the aged and infirm who were turned away from the homes of hard masters, who had been enriched by their toil, our benevolent societies supported while they lived, and buried when they died, and comparatively few of us have found it necessary to ask for Government rations, which have been so bountifully bestowed upon the unrepentant Rebels of Richmond. . . . During the. . . Slaveholders' Rebellion we have been true and loyal to the United States Government; . . . We have given aid and comfort to the soldiers of freedom (for which several of our people, of both sexes, have been severely punished by stripes and imprisonment). We have been their pilots and their scouts, and have safely conducted them through many perilous adventures. . . .

Reprinted from We Ask Only for Even-Handed Justice. Black Voices from Reconstruction 1865-1977. Copyright © 2014 by University of Massachusetts Press. Published by the University of Massachusetts Press. (Document 4.7.8)

Bring students together in a large circle for a Socratic Seminar. If the class is large, consider creating two smaller circles. Explain that the purpose of a Socratic seminar is to consider an issue from different perspectives through the use of student-led questioning. In a Socratic seminar, students ask and answer questions about a given text or source, and conversation flows more organically than in a teacher-led discussion.

For this seminar, have students read “Of the Dawn of Freedom,” a chapter from W.E.B. DuBois’s seminal text The Souls of Black Folk (pdf available in source and audio can be found on linked website). Since the text is quite lengthy, consider assigning it for homework or giving an additional class period for students to read and analyze the source prior to the discussion. Alternatively, assign each student 2-3 pages of the text and have them report out responses to the question below before doing a written reflection.

Note that this link directs you to a website that also contains audio and PDF versions of the text to differentiate for your students.

After the seminar, have students answer the following question in a written reflection:

Have students do background research on the history of the federal holiday of Juneteenth using the internet or selected picture books or texts. Have a quick class discussion using the following questions:

Place students into small groups and instruct each group to come up with a museum exhibit that teaches about Juneteenth and honors the history of emancipation. Each exhibit should include:

Set up all the group exhibits in one space–perhaps the school’s library or auditorium–and invite other students outside the class to visit the museum and engage with the group exhibits. Lead a closing discussion with the class and ask them to consider the guiding question (to what extent did emancipation’s promise match its reality for Black Americans?) one last time, in light of the various exhibits they created.

Please login or sign up to access the student view functions.