Unit

Years: 1877 to 1950

Historical Events, Movements, and Figures

Before beginning this lesson, students should have prior knowledge of Jim Crow laws, segregation, and the roots of White supremacist violence in the post-Reconstruction South, including the legacy of the KKK. A review of landmark Supreme Court cases regarding Black legal rights and the long fight for accountability and justice would also support students before starting this lesson–especially the Dred Scott decision and Plessy v. Ferguson.

You may want to consider prior to teaching this lesson: Plessy v. Ferguson

Lynching was a form of racial terrorism in the post-Reconstruction South and one means of maintaining power in the hands of White supremacists. For decades individuals and organizations worked to end it. However, even in courts of law, Black men, women, and children were often failed by the legal system. The case of the Scottsboro 9, sometimes known as the Scottsboro Boys, provides an example of how difficult it was to find justice and legal accountability in the face of widespread systemic racism and violence.

Introduction

Lynching is defined as any killing or public execution that occurs outside of the legally recognized justice system, often by a group. During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, lynching was often associated with a mob action, murdering a person without lawful trial, especially by White supremacists against African American men and women. This idea of “people’s retribution” became more common after Reconstruction, when the federal government withdrew its military from the South and White Southerners lynched hundreds of Black Americans as a form of racial terrorism. The Equal Justice Initiative has documented over 4,000 lynchings of Black people between 1877 and 1950. Not all victims of lynch mobs were Black, but the vast majority were. And those victims who were White were seen as social outsiders–Italian immigrants, Jewish people, and Catholics.

Lynching

In a typical lynching, mobs ranging from tens to thousands of people surrounded a jail, “overpowered” the local officials, and took the accused person often into the countryside. Most lynchings happened in the South, but there were also many in the North and the frontier West. White lynch mobs often justified lynchings by claiming that they were protecting White “womanhood” from the “lust and barbarity” of Black men; many victims of lynchings were falsely accused of rape, and Emmett Till was lynched in 1955 for allegedly looking at a White woman in a way that offended her. Far and away, most allegations that led to lynchings were lies to justify a reign of racial terror that would subdue Black communities and enforce segregation in Jim Crow America. The Equal Justice Initiative estimates that six million Black Americans fled the South as a direct result of racial terror lynchings.

As time progressed, lynchings became ever more gruesome and bizarre, particularly in the South. Lynchings were often publicized ahead of time and thousands of people of all ages arrived from other states to find a macabre carnival atmosphere. Victims were tortured for hours until sometimes they were burned alive as they were hung. Participants might collect body parts as “souvenirs,” and they documented the horrific images that they saw on commercial postcards that were sent through the mail, with messages like, “We attended a barbecue last night.” “Lynching,” says English Professor Jacqueline Goldsby, “both requires and defies our understanding. Whether we like it or not, it’s one of the touchstones of American culture.”

Ida B. Wells and the Anti-Lynching Campaign

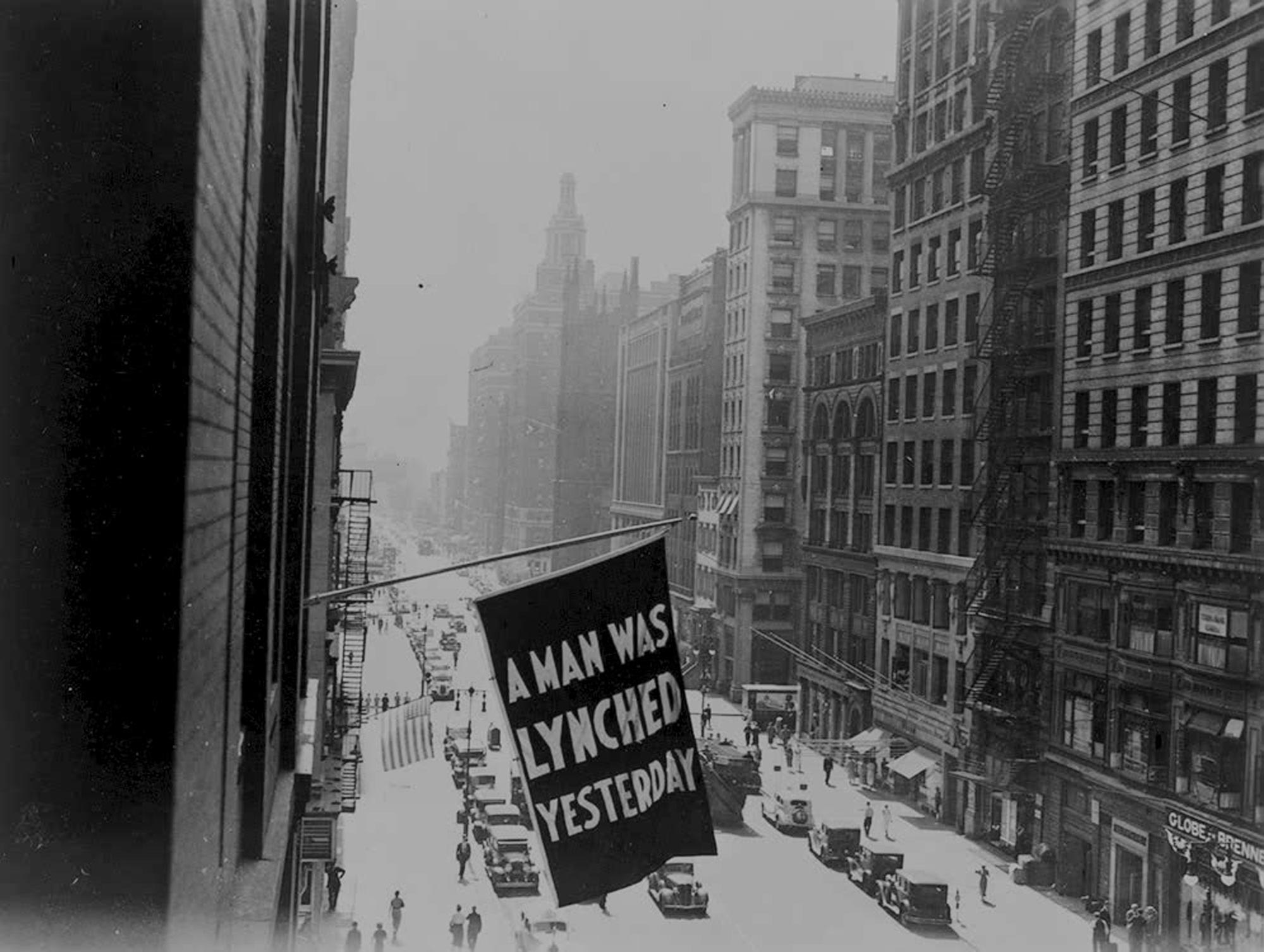

Black communities tried to raise awareness of the severity of the problem, especially among Northern Whites who were relatively shielded from the everyday terrorism of lynching. In 1892, Ida B. Wells was a young journalist in Memphis, Tennessee, when three prominent young businessmen whom she knew personally were murdered by a lynch mob. Wells responded to this experience by initiating a life-long campaign to raise awareness about the frequency of lynching and to hold the media and U.S. institutions accountable. The writings of Ida B. Wells-Barnett began a groundswell of activism that reached from African American churches and national organizations such as the NAACP and the Communist-initiated International Labor Defense, all the way to Congress and the White House.

Legal Accountability and the Scottsboro Case

Legal accountability for lynchings remained elusive for decades, despite several attempts at Congressional action. In January 1901, George Henry White, a Congressional representative who was formerly enslaved, proposed a bill that would have made the lynching of human beings a federal crime. It was easily defeated. In 1918, Congressman Leonidas Dyer of Missouri introduced a bill that held local and state governments legally and financially responsible for lynching in their jurisdiction. “We can no longer permit open contempt of the courts and lawful procedure. We can no longer endure the burning of human beings in public in the presence of women and children,” he said. This bill passed the House, but lost in the Senate. Another attempt, the Costigan-Wagner Bill, was blocked by Southern Congressmen in the 1930s. When President Harry Truman introduced civil rights legislation that included anti-lynching provisions in 1948, it too failed.

In the absence of Congressional action, Black Americans turned to the courts for accountability, but long-standing systemic inequality existed there, too. In March 1931, nine Black teenagers, all boys ages thirteen through nineteen and mostly unknown to each other, had hitched a ride on a freight train from Chattanooga to Memphis in a desperate effort to find paying work. After an altercation with a group of White youths, also riding the rails, the train stopped in Paint Rock, Alabama, where two White women on the train falsely accused all nine Black teenagers of gang-raping them. The Black teenagers were hauled into the Scottsboro, Alabama jail and their case evolved into one of the most sensationalized and complicated of the early twentieth century, receiving global attention. It was quite clear from later testimony that the young men were innocent. Yet they grew into manhood in jail, no justice in sight. Upon appeal, the case made it to the U.S. Supreme Court, which ruled that the exclusion of African Americans from their jury pool was unconstitutional according to the 6th and 14th Amendments. Still, several of the defendants remained imprisoned for a crime with scant evidence, and the case is widely remembered as a failure of justice.

The case of the Scottsboro 9 and Ida B. Well’s anti-lynching campaign shed a sharp light on the continued inequities of the U.S. legal system, and highlighted the violence, double standards, and structural racism in the court system as well as throughout American institutions.

Alexander, Michelle. The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness. New York: New Press, 2010.

Allen, James, Hilton Als, & Leon F. Litwack, eds. Without Sanctuary: Lynching Photography in America (with a forward by Congressman John Lewis). Santa Fe, NM: Twin Palms Publishers, 2000.

Burns, Ken, Jazz PBS (2001) Episodes One, Two, Five and Six of the ten-part, eighteen-hour documentary address lynching.

Dray, Philip. At the Hands of Persons Unknown: The Lynching of Black America. New York: Random House, 2002.

Equal Justice Initiative. “Confronting Lynching.” LYNCHING IN AMERICA: Confronting the Legacy of Racial Terror, Equal Justice Initiative, 2017, pp. 57–64. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep30688.8. Accessed 26 May 2023.

“Lynching in America.” Equal Justice Initiative. https://lynchinginamerica.eji.org/

Fradin, Dennis B. and Judith Bloom Fradin. Ida B. Wells : Mother of the Civil Rights Movement. New York: Clarion Books, 2000.

Ginzburg, Ralph. One Hundred Years of Lynchings. Baltimore, MD: Black Classic Press, 1997.

Goodman, Barak, Scottsboro: An American Tragedy (2000) PBS, American Experience.

Goodman, James. Stories of Scottsboro: The Rape Case that Shocked 1930s America and Revived the Struggle for Equality. New York: Pantheon Press, 1994.

Raiford, Leigh. “Photography and the Practices of Critical Black Memory.” History and Theory, vol. 48, no. 4, 2009, pp. 112–29. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/25621443. Accessed 26 May 2023.

“Scottsboro: An American Tragedy.” American Experience, PBS, 2001. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/films/scottsboro/

Stevenson, Bryan. Just Mercy : a Story of Justice and Redemption. New York: Spiegel & Grau, 2014.

Whitaker, Hugh Stephen. “A Case Study in Southern Justice: The Murder and Trial of Emmett Till.” Rhetoric and Public Affairs, vol. 8, no. 2, 2005, pp. 189–224. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41939980. Accessed 26 May 2023.

Williams, Lynn Barstis. “Images of Scottsboro.” Southern Cultures, vol. 6, no. 1, 2000, pp. 50–67. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/26236828. Accessed 26 May 2023.

WOOD, AMY LOUISE, and SUSAN V. DONALDSON. “Lynching’s Legacy in American Culture.” The Mississippi Quarterly, vol. 61, no. 1/2, 2008, pp. 5–25. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/26476641. Accessed 26 May 2023.

Due to the nature of the charges associated with the Scottsboro 9, this lesson delves into sexual violence. As a result, careful consideration should be given to the age, maturity and past experiences of students. Rape should be clearly identified as a form of sexual violence that is forced on someone against their will and that can lead to both physical and emotional harm. A trauma-informed approach and plan should be in place to support students who may have experience with sexual violence.

Lynching is an extremely violent and traumatic reality of Black history in the United States and should also be presented from a trauma-informed lens. It is imperative that teachers are sensitive to the emotional reactions of their students when discussing details of lynchings. While photographic documentation of lynchings is widely available online and may support some lesson activities, we recommend using photos with caution and using content warnings beforehand, as some students may be triggered by such graphic depictions of racial violence.

Recent scholarship refers to lynching as racial terrorism, and we recommend that teachers adopt this language to make it clear to students the extent to which lynching brutalized and traumatized Black communities.

Finally, the Equal Justice Initiative’s National Memorial for Peace and Justice opened in 2017 to honor the victims of racial terror lynchings, to prompt meaningful reflection, and to confront the traumatic and lasting legacy of lynching on Black Americans. The EJI’s website is a valuable resource for teachers considering a visit to the memorial in connection with this lesson.

Lynching, a public execution committed by a group without any legal action or trial, was an extremely violent and traumatic reality for Black Americans living in Jim Crow America. Lynching amounted to racial terrorism, and White supremacists commonly tortured and killed their victims publicly while White audiences cheered them on. Not all victims of lynch mobs were Black, but the vast majority were, and the Equal Justice Initiative has documented over 4,000 lynchings of Black people between 1877 and 1950.

While journalist Ida B. Wells-Barnett published numerous articles to expose the horrors of lynching and hold public officials and institutions accountable, Congress and the courts failed to act. At the same time, Black Americans fought for justice in the court system. In the case of the “Scottsboro 9,” nine Black teenagers were falsely accused of rape and unjustly imprisoned. The Scottsboro 9 faced all-white juries, lynch mobs, and other legal barriers to accountability, but their case eventually led to new legal protections for Black citizens to access a free and fair trial. In the end, the anti-lynching campaign and Scottsboro case set the stage for broader activism in the civil rights movement.

Select the activities and sources you would like to include in the student view and click “Launch Student View.”

It is highly recommended that you review the Teaching Tips and sources before selecting the activities to best meet the needs and readiness of your students. Activities may utilize resources or primary sources that contain historical expressions of racism, outdated language or racial slurs.

Put students in small groups, and give each group a copy of the lynching statistics. Together, they should discuss the following questions:

Have a full class discussion on the following questions:

As an optional extension for more mature classes, consider showing photographs of lynching postcards to students to discuss the human toll of lynching beyond the numbers. Give a content warning, and ensure your students are emotionally prepared for viewing such graphic violence. Photographs are widely available online from websites such as Without Sanctuary or Truth in Photography. If your students are not ready to see images, consider using a song like Billie Holiday’s “Strange Fruit” or with explanation the images in Activity 5 which are edited photos by Ken Gonzales-Day instead. Hold a discussion of the following questions:

For this Socratic Seminar, have students read the Ida B. Well’s speech “Lynching, Our National Crime” which she delivered in 1909 to the organization that would become the NAACP.

After the seminar, lead a reflection in which students answer the following questions:

On the board, make a list of the institutions below that hold very important roles in our communities. Explain that institutions have sometimes protected Black communities, and other times have failed Black communities. For each institution, have students work in pairs to list out the social and legal safeguards that each provides, as well as the ways in which each institution prevents progress or can potentially harm Black communities. (Do an example with one of the institutions on the board so students have a model.)

Divide up the institutions, and have the student pairs conduct internet research how their assigned institution responded to the problem of lynching. They should locate at least one specific example of the institutional response, and then share out with the class. Hold a discussion of the following questions:

Divide students into groups and give each group one of the following documents. Each document demonstrates the ways in which one person or group fought to end lynching.

Have each group create a poster that answers the following questions about their document. Students may conduct additional research to answer the questions. Students should teach the class about their assigned person or group using the poster as a visual aid.

Excerpts from “The Malicious and Untruthful White Press,” by Ida B. Wells, 1892

Ida B. Wells (1862–1931) was born in Holly Springs, Mississippi to enslaved parents, six months before the Emancipation Proclamation. She attended Rust College until her mother, father, and youngest sibling died in a yellow fever epidemic, at which time she took on the responsibility of supporting herself and her six younger brothers and sisters. She became a teacher.

In 1884, Wells was asked to move to the smoking car of a train on the way to her first teaching job. When she refused, two conductors tried to physically force her into the smoking section. She got off the train instead and filed a discrimination lawsuit. She was awarded $500 dollars, but the verdict was reversed three years later by Tennessee’s Supreme Court.

After Wells was fired from her teaching position because she wrote an editorial accusing the Memphis school board of not providing enough resources for black schools, she turned to a career in journalism. Her writing was direct and provocative, and in retaliation, Whites destroyed the offices and press of Free Speech, the paper for which she wrote.

Ida Wells moved to Chicago and continued to write and speak against lynching and for civil rights for African Americans. In 1906, she joined with W. E. B. DuBois and others to further the Niagara Movement, and she was one of two African American women to sign “the call” to form the NAACP in 1909. In 1930, she was one of the first Black women to run for public office in the United States. A year later, she passed away after a lifetime of activism.

The Daily Commercial and Evening Scimitar of Memphis Tenn., are owned by leading business men of that city, and yet in spite of the fact that there had been no white woman outraged by an Afro-American, and that Memphis possessed a thrifty law-abiding property-owning class of Afro-Americans the Commercial of May 17 [1892], under the head of “More Rapes, More Lynchings” gave utterance to the following:

The lynching of three Negro scoundrels reported in our dispatches from Anniston, Ala., for a brutal outrage committed upon a white woman will be a text for much comment on “Southern barbarism” by Northern newspapers; but we fancy it will hardly prove effective for campaign purposes among intelligent people. The frequency of these lynchings calls attention to the frequency of the crimes which cause lynching. The “Southern barbarism” which deserves the attention of all people North and South, is the barbarism which preys upon the weak and defenseless woman. Nothing but the most prompt, speedy and extreme punishment can hold in check the horrible and beastial propensities of the Negro race. There is a strange similarity about a number of cases of this character which have lately occurred.

In each case the crime was deliberately planned and perpetrated by several Negroes. They watched for an opportunity when the women were left without a protector. It was not a sudden yielding to a fit of passion, but the consummation of a devilish purpose which has been seeking and waiting for the opportunity….The swift punishment which invariably follows these horrible crimes doubtless acts as a deterring effect upon the Negroes in that immediate neighborhood for a short time. But the lesson is not widely learned nor long remembered…The facts of the crime appear to appeal more to the Negro’s lustful imagination that the facts of the punishment do to his fears. He sets aside all fear of death in any form when opportunity is found for gratification of his bestial desires….

…The generation of Negroes which have grown up since the Civil War have lost in large measure the traditional and wholesome awe of the white race which kept the Negroes in subjection, even when their masters were in the army, and their families left unprotected except by the slaves themselves. There is no longer a restraint upon the brute passion of the Negro.

What is to be done? The crime of rape is always horrible, but to the Southern man there is nothing which so fills the soul with horror, loathing and fury as the outraging of a white woman by a Negro. It is the race question in the ugliest, vilest, most dangerous aspect. The Negro as a political factor can be controlled. But neither laws nor lynchings can subdue his lusts. Sooner or later it will force a crisis…

In its issue of June 4, the Memphis Evening Scimitar gives the following excuse for lynch law:

Aside from the violation of white women by Negroes, which is the outcropping of a bestial perversion of instinct, the chief case of the trouble between the races in the South is the Negro’s lack of manners. In the state of slavery he learned politeness from association with white people, who took pains to teach him. Since the emancipation came and the tie of mutual interest and regard between master and servant was broken, the Negro has drifted away into a state which is neither freedom nor bondage. Lacking the proper inspiration of the one and the restraining force of the other he has taken up the idea that boorish insolence is independence and the exercise of a decent degree of breeding toward white people is identical to servile submission. In consequence of the prevalence of this notion there are many Negroes who use every opportunity to make themselves offensive, particularly when they think it can be done with impunity.

We have too many instances right here in Memphis to doubt this and our experience is not exceptional. The white people won’t stand for this sort of thing, and whether they be insulted as individuals or as a race, the response will be prompt and effectual. The bloody riot of 1866, in which so many Negroes perished, was brought principally by the outrageous conduct of the blacks toward the whites on the streets. It is also a remarkable and discouraging fact that the majority of such scoundrels are Negroes who have received educational advantages at the hands of white taxpayers. They have got just enough of learning to make them realize how hopelessly their race is behind the other in everything that makes a great people, and the attempt to “get even” by insolence, which is ever the resentment of inferiors. There are well-bred Negroes among us, and it is truly unfortunate that they should have to pay, even in part, the penalty of the offenses committed the baser sort, but this is the way of the world….

On March 9th, 1882, there were lynched in this same city [Memphis] three of the best specimens of young since-the-war Afro-American manhood. They were peaceful, law-abiding citizens and energetic business men.

They believed the problem was to be solved by eschewing politics and putting money in the purse. They owned a flourishing grocery business in a thickly populated suburb of Memphis, and a white man named Barrett had one on the opposite corner. After a personal difficulty which Barrett sought by going into the "People's Grocery" drawing a pistol and was thrashed by Calvin McDowell, he (Barrett) threatened to "clean them out." These men were a mile beyond the city limits and police protection; hearing that Barrett's crowd was coming to attack them Saturday night, they mustered forces and prepared to defend themselves against the attack.

When Barrett came he led a posse of officers, twelve in number, who afterward claimed to be hunting a man for whom they had a warrant. That twelve men in citizen's clothes should think it necessary to go in the night to hunt one man who had never before been arrested, or made any record as a criminal has never been explained. When they entered the back door the young men thought the threatened attack was on, and fired into them. Three of the officers were wounded, and when the defending party found it was officers of the law upon whom they had fired, they ceased and got away.

Thirty-one men were arrested and thrown in jail as "conspirators," although they all declared more than once they did not know they were firing on officers. Excitement was at fever heat until the morning papers, two days after, announced that the wounded deputy sheriffs were out of danger. This hindered rather than helped the plans of the whites. There was no law on the statute books which would execute an Afro-American for wounding a white man, but the "unwritten law" did. Three of these men, the president, the manager and clerk of the grocery"—the leaders of the conspiracy"—were secretly taken from jail and lynched in a shockingly brutal manner. "The Negroes are getting too independent," they say, "we must teach them a lesson."

What lesson? The lesson of subordination. "Kill the leaders and it will cow the Negro who dares to shoot a white man, even in self defense."

Although the race was wild over the outrage, the mockery of law and justice which alarmed men and locked them up in jails where they could be easily and safely reached by the mob—the Afro-American ministers, newspapers and leaders counselled obedience to the law which did not protect them.

Their counsel was heeded and not a hand was uplifted to resent the outrage; following the advice of the Free Speech, people left the city in great numbers.

Source: Reprinted in Wells-Barnett, Ida. On Lynchings. Introduction by Patricia Hill Collins. NY: Humanity Books, 2002. (Document 5.10.4)

“Lynch Law Condemned,” Cleveland Gazette, December 9, 1899

Lynch Law Condemned

President McKinley had the following in his annual message to congress last Monday: “Those who, in disregard of law and the public peace, unwilling to await the judgment of court or jury, constitute themselves judges and executioners, should not escape the severest penalties for their crimes.”

“What I said in my inaugural address of March 4, 1897. I now repeat: The constituted authorities must be cheerfully and vigorously upheld. Lynchings must not be tolerated in a great and civilized country like the United States. Courts, not mobs, must execute the penalties of the laws. The preservation of public order, the right of discussion, the integrity of courts, and the orderly administration of justice must continue forever the rock of safety upon which our government securely rests.”

Source: http://dbs.ohiohistory.org/africanam/page.cfm?ID=19239. (Document 5.10.5)

It is a source of deep regret and sorrow to many good Christians in this country that the church puts forth so few and such feeble protests against lynching. As the attitude of many ministers on the question of slavery greatly discouraged the abolitionists before the war, so silence in the pulpit concerning the lynching of negroes to-day plunges many of the persecuted race into deep gloom and dark despair. Thousands of dollars are raised by our churches every year to send missionaries to Christianize the heathen in foreign lands, and this is proper and right. But in addition to this foreign missionary work, would it not be well for our churches to inaugurate a crusade against the barbarism at home, which converts hundreds of white women and children into savages every year, while it crushes the spirit, blights the hearth and breaks the hearts of hundreds of defenceless blacks? Not only do ministers fail, as a rule, to protest strongly against the hanging and burning of negroes, but some actually condone the crime without incurring the displeasure of their congregations or invoking the censure of the church. Although the church court which tried the preacher in Wilmington, Delaware, accused of inciting his community to riot and lynching by means of incendiary sermon, found him guilty of “unministerial and unchristian conduct,” of advocating mob murder and of thereby breaking down the public respect for the law, yet it simply admonished him to be “more careful in the future” and inflicted no punishment at all.

Such indifference to lynching on the part of the church recalls the experience of Abraham Lincoln, who refused to join a church in Springfield, Illinois, because only three out of twenty-two ministers in the whole city stood with him in his effort to free the slave. But, however unfortunate may have been the attitude of some churches on the question of slavery before the war, from the moment the shackles fell from the black man’s limbs to the present day, the American Church has been most kind and generous in its treatment of the backward and struggling race. Nothing but ignorance or malice could prompt one to disparage the efforts put forth by the churches in the negro’s behalf. But, in the face of so much lawlessness to-day, surely there is a role for the Church Militant to play. …

Source: North American Review, 178, (1904): pp. 853-68. (Document 5.10.6)

Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill, 1922

Congressman Leonidas Dyer of Missouri introduced this bill in 1918. It was designed to act as a deterrent to lynching nationwide by seeking to punish state, county and local officials who failed to prevent its occurrence. ‘We can no longer permit open contempt of the courts and lawful procedure. We can no longer endure the burning of human beings in public in the presence of women and children,” Dyer wrote in his report. The bill brought the crime of lynching into a public forum for the country to argue and decide. Both men and women, Black and White, mobilized widely and came out in support of the Dyer Bill. Aided by numerous organizations, the bill passed the House, but lost in the Senate due to filibustering by Southern politicians. The NAACP abandoned its efforts when the Dyer Bill failed in the Senate, but resumed its pressure for such legislation again in 1930, in the form of the Costigan-Wagner Bill.

AN ACT To assure to persons within the jurisdiction of every State the equal protection of the laws and to punish the crime of lynching.

Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled. That the phrase “mob or riotous assemblage” when used in this act, shall mean an assemblage composed of three or more persons acting in concert for the purpose of depriving any person of his life without authority of law as a punishment for or to prevent the commission of some actual or supposed public offense.

Sec. 2. That if any State or governmental subdivision thereof fails, neglects, or refuses to provide and maintain protection to the life of any person within its jurisdiction against a mob or riotous assemblage, such State shall by reason of such failure, neglect, or refusal be deemed to have denied to such person the equal protection of the laws of the State, and to the end that such protection as a guaranteed to the citizens of the United States by its Constitution may be secured it is provided:

Sec. 3. That any state or municipal officer charged with the duty or who possesses the power or the authority as such officer to protect the life of any person that may be put to death by any mob or riotous assemblage, or who has any such person in his charge as a prisoner, who fails, neglects, or refuses to make all reasonable efforts to prevent such person from being so put to death, or any state or municipal officer charged with the duty of apprehending or prosecuting any person participating in such mob riotous assemblage who fails, neglects, or refuses to make all reasonable efforts to perform his duty in apprehending or prosecuting to final judgment under the laws of such state all persons so participating except such, if any, as are or have been held to answer for such participation in any district court of the United States, as herein provided, shall be guilty of a felony, and upon conviction thereof shall be punished by imprisonment not exceeding five years or by a fine of not exceeding $5,000, or by both such fine and imprisonment.

Any state or municipal officer, acting as such officer under authority of State law, having in his custody or control a prisoner, who shall conspire, combine, or confederate with any person to put such prisoner to death without authority of law as a punishment for some alleged public offense, or who shall conspire, combine, or confederate with any person to suffer such prisoner to be taken or obtained from his custody or control for the purpose of being put to death without authority of law as a punishment for an alleged public offense, shall be guilty of a felony, and those who so conspire, combine, or confederate with such officer shall likewise be guilty of a felony. On conviction the parties participating therein shall be punished by imprisonment for life or not less than five years.

Sec. 4. That the district court of the judicial district wherein a person is put to death by a mob or riotous assemblage shall have jurisdiction to try and punish, in accordance with the laws of the State where the homicide is committed, those who participate therein: Provided, That it shall be charged in the indictment that by reason of the failure, neglect, or refusal of the officers of the State charged with the duty of prosecuting such offense under the laws of the State to proceed with due diligence to apprehend and prosecute such participants the state has denied to its citizens the equal protection of the laws. It shall not be necessary that the jurisdictional allegations herein required shall be proven beyond a reasonable doubt, and it shall be sufficient if such allegations are sustained by a preponderance of the evidence.

Sec. 5. That any county in which a person is put to death by a mob or riotous assemblage shall, if it is alleged and proven that the officers of the State charged with the duty of prosecuting criminally such offense under the laws of the State have failed, neglected, or refused to proceed with due diligence to apprehend and prosecute the participants, the mob or riotous assemblage, forfeit $10,000, which sum may be recovered by an action therefor in the name of the United States against such county for the use of the family, if any, of the person so put to death; if he had no family, then to his dependent parents, if any; otherwise for the use of the United States. Such action shall be brought and prosecuted by the district attorney of the United States of the district in which such county is situated in any court of the United States having jurisdiction therein. If such forfeiture is not paid upon recovery of a judgment therefor, such court shall have jurisdiction to enforce payment thereof by levy of execution upon any property of the county, or may compel the levy and collection of a tax, therefor, or may otherwise compel payment thereof by mandamus or other appropriate process; and any officer of such county or other person who disobeys or fails to comply with any lawful order of the court in the premises shall be liable to punishment as for contempt and to any other penalty provided by law therefor.

Sec. 6. That in the event that any person so put to death shall have been transported by such mob or riotous assemblage from one county to another county during the time intervening between his capture and putting to death, the county in which he is seized and the county in which he is put to death shall be jointly and severally liable to pay the forfeiture herein provided.

Sec. 7. That any act committed in any State or Territory of the United States in violation of the rights of a citizen or subject of a foreign country secured to such citizen or subject by treaty between the United States and such foreign country, which act constitutes a crime under the laws of such State or Territory, shall constitute a like crime against the peace and dignity of the United States, punishable in like manner as in the courts of said State or Territory, and within the period limited by the laws of such State or Territory, and may be prosecuted in the courts of the United States, and upon conviction the sentence executed in like manner as sentences upon convictions for crimes under the laws of the United States.

Sec. 8. That in construing and applying this act the District of Columbia shall be deemed a county, as shall also each of the parishes of the State of Louisiana.

That if any section or provision of this act shall be held by any court to be invalid, the balance of the act shall not for that reason be held invalid.

Source: Senate Reports (7951), 67th Congress: 2nd Session, 1921-22, Vol. 2. (Document 5.10.7)

Letter from Eleanor Roosevelt to Walter White, Director of NAACP, March 10, 1936

President Roosevelt’s wife was supportive of the growing campaign to pass federal anti-lynching legislation. In this letter, she acknowledges President Roosevelt’s lack of support and suggests other strategies. FDR was concerned that pressing for a bill such as Costigan-Wagner would decrease the chances of his New Deal legislative agenda passing Congress.

THE WHITE HOUSE

WASHINGTON

March 19, 1936

My dear Mr. White:

Before I received your letter today I had been in to the President, talking to him about your letter enclosing that of the Attorney general. I told him that it seemed rather terrible that one could get nothing done and that I did not blame you in the least for feeling there was no interest in this very serious question. I asked him if there were any possibility of getting even one step taken, and he said the difficulty is that it is unconstitutional apparently for the Federal Government to step in in the lynching situation. The Government has only been allowed to do anything about kidnapping because of its interstate aspect, and even that has not as yet been appealed so they are not sure that it will be declared constitutional.

The President feels that lynching is a question of education in the states, rallying good citizens, and creating public opinion so that the localities themselves will wipe it out. However, if it were done by a Northerner, it will have an antagonistic effect. I will talk to him again about the Van Nuys resolution and will try to talk also to Senator Byrnes and get his point of view. I am deeply troubled about the whole situation as it seems to be a terrible thing to stand by and let it continue and feel that one cannot speak out as to his feeling. I think your next step would be to talk to the more prominent members of the Senate.

Very sincerely yours,

Eleanor Roosevelt

Source: www.assumption.edu/acad/ii/Academic/history/Hi113net/ERphotocopy.html. (Document 5.10.10)

Show students several selected photoes from Ken Gonzales-Day or visit his site to select other edited photos by Day, who has recreated several images of lynchings by removing the victims from the image. Have each student choose one image and answer the following questions about it in writing:

Then have students read Ken Gonzales-Day’s artist statement about this series of photos. Have a class discussion using the following questions:

As an introduction to the Scottsboro Case, have students work in small groups to create a timeline of important events related to structural racism in the justice system. Students can make a paper timeline on chart paper or poster board or an electronic timeline using software such as Canva or Jamboard. Timelines should include the events below, and students should write a 1 sentence description of the event on the timeline to ensure they understand the event and its significance.

Hold a discussion on the following question:

Place students into two groups and assign each group to read one of two Supreme Court decisions regarding the Scottsboro defendants–Powell v. Alabama in 1932 and Norris v. Alabama from 1935. Students should work together and use the OPCVL protocol to analyze the source.

Have a representative from each group share a summary of the group’s discussion. Have a discussion using the following questions to compare and contrast the two Supreme Court decisions and their implications for Black Americans.

Finally, have students write an individual reflection to the following prompt:

Excerpts from the majority opinion of the U.S. Supreme Court in Powell v. State of Alabama, November 1932

After the Alabama Supreme Court upheld all but one of the eight Scottsboro convictions and death sentences, by a 6–1 vote in January, 1932, the lawyers for the International Defense League appealed the cases to the United States Supreme Court. In the landmark case of Powell v. Alabama, the Court, 7– 2, overturned the convictions. This meant that there would have to be new trials for each of them.

OZIE POWELL, WILLIE ROBERSON, ANDY WRIGHT, AND OLEN MONTGOMERY v. ALABAMA; HAYWOOD PATTERSON v. SAME; CHARLEY WEEMS AND CLARENCE NORRIS v. SAME

Nos. 98, 99, 100

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

NOVEMBER 7, 1932, DECIDED

Even the intelligent and educated layman has small and sometimes no skill in the science of law. If charged with crime, he is incapable, generally, of determining for himself whether the indictment is good or bad. He is unfamiliar with the rules of evidence. Left without the aid of counsel he may be put on trial without a proper charge, and convicted upon incompetent evidence, or evidence irrelevant to the issue or otherwise inadmissible. He lacks both the skill and knowledge adequately to prepare his defense, even though he had a perfect one. He requires the guiding hand of counsel at every step in the proceedings against him. Without it, though he be not guilty, he faces the danger of conviction because he does not know how to establish his innocence. If that be true of men of intelligence, how much more true is it of the ignorant and illiterate, or those of feeble intellect. If in any case, civil or criminal, a state or federal court were arbitrarily to refuse to hear a party by counsel, employed by and appearing for him, it reasonably may not be doubted that such a refusal would be a denial of a hearing, and, therefore, of due process in the constitutional sense…

In the light of the facts outlined in the forepart of this opinion—the ignorance and illiteracy of the defendants, their youth, the circumstances of public hostility, the imprisonment and the close surveillance of the defendants by the military forces, the fact that their friends and families were all in other states and communication with them necessarily difficult, and above all that they stood in deadly peril of their lives—we think the failure of the trial court to give them reasonable time and opportunity to secure counsel was a clear denial of due process.

The United States by statute and every state in the Union by express provision of law, or by the determination of its courts, make it the duty of the trial judge, where the accused is unable to employ counsel, to appoint counsel for him. In most states the rule applies broadly to all criminal prosecutions, in others it is limited to the more serious crimes, and in a very limited number, to capital cases. A rule adopted with such unanimous accord reflects, if it does not establish, the inherent right to have counsel appointed, at least in cases like the present, and lends convincing support to the conclusion we have reached as to the fundamental nature of that right.

The judgments must be reversed and the causes remanded for further proceedings not inconsistent with this opinion.

Judgments reversed.

Source: 287 U.S. 45, 1932 available online at www.law.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/FTrials/scottsboro/SB_powus.html. (Document 5.10.13)

Excerpts from the majority opinion of the U.S. Supreme Court in Norris v. State of Alabama, 1935

On February 15, 1935, the United States Supreme Court heard appeals for both the Haywood Patterson and Clarence Norris cases. Their lawyer argued that the convictions should be overturned because Alabama excluded Blacks from its jury rolls in violation of the equal protection clause of the Constitution. The lawyers were able to prove that names of African Americans that appeared on the jury rolls introduced in the Alabama lower court were forged sometime after the start of Patterson's trial. The Supreme Court unanimously reversed the convictions of Norris and Patterson, and in Norris vs. Alabama, unequivocally held that the Alabama system of jury selection was unconstitutional.

No. 534

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

294 U.S. 587; 55 S. Ct. 579

February 15, 18, 1935, Argued

April 1, 1935, Decided

Third. The evidence on the motion to quash the trial venire. The population of Morgan County, where the trial was had, was larger than that of Jackson County, and the proportion of negroes was much greater. The total population of Morgan County in 1930 was 46,176, and of this number 8,311 were negroes.

Within the memory of witnesses, long resident there, no negro had ever served on a jury in that county or had been called for such service. Some of these witnesses were over fifty years of age and had always lived in Morgan County. Their testimony was not contradicted. A clerk of the circuit court, who had resided in the county for thirty years, and who had been in office for over four years, testified that during his official term approximately 2500 persons had been called for jury service and that not one of them was a negro; that he did not recall "ever seeing any single person of the colored race serve on any jury in Morgan County."

There was abundant evidence that there were a large number of negroes in the county who were qualified for jury service. Men of intelligence, some of whom were college graduates, testified to long lists (said to contain nearly 200 names) of such qualified negroes, including many business men, owners of real property and householders. When defendant's counsel proposed to call many additional witnesses in order to adduce further proof of qualifications of negroes for jury service, the trial judge limited the testimony, holding that the evidence was cumulative.

We find no warrant for a conclusion that the names of any of the negroes as to whom this testimony was given, or of any other negroes, were placed on the jury rolls. No such names were identified. The evidence that for many years no negro had been called for jury service itself tended to show the absence of the names of negroes from the jury rolls, and the State made no effort to prove their presence. The trial judge limited the defendant's proof "to the present year, the present jury roll." The sheriff of the county, called as a witness for defendants, scanned the jury roll and after "looking over every single name on that jury roll, from A to Z," was unable to point out "any single negro on it."

For this long-continued, unvarying, and wholesale exclusion of negroes from jury service we find no justification consistent with the constitutional mandate We have carefully examined the testimony of the jury commissioners upon which the state court based its decision. One of these commissioners testified in person and the other two submitted brief affidavits. By the state act (Gen. Acts, Ala., 1931, No. 47, p. 55), in force at the time the jury roll in question was made up, the clerk of the jury board was required to obtain the names of all male citizens of the county over twenty-one and under sixty-five years of age, and their occupation, place of residence and place of business. (Id., p. 58, § 11.) The qualifications of those who were to be placed on the jury roll were the same as those prescribed by the earlier statute which we have already quoted. (Id., p. 59, § 14.) The member of the jury board, who testified orally, said that a list was made up which included the names of all male citizens of suitable age; that black residents were not excluded from this general list; that in compiling the jury roll he did not consider race or color; that no one was excluded for that reason; and that he had placed on the jury roll the names of persons possessing the qualifications under the statute. The affidavits of the other members of the board contained general statements to the same effect.

We think that this evidence failed to rebut the strong prima facie case which defendant had made. That showing as to the long-continued exclusion of negroes from jury service, and as to the many negroes qualified for that service, could not be met by mere generalities. If, in the presence of such testimony as defendant adduced, the mere general assertions by officials of their performance of duty were to be accepted as an adequate justification for the complete exclusion of negroes from jury service, the constitutional provision—adopted with special reference to their protection—would be but a vain and illusory requirement. The general attitude of the jury commissioner is shown by the following extract from his testimony: "I do not know of any negro in Morgan County over twenty-one and under sixty-five who is generally reputed to be honest and intelligent and who is esteemed in the community for his integrity, good character and sound judgment, who is not an habitual drunkard, who isn't afflicted with a permanent disease or physical weakness which would render him unfit to discharge the duties of a juror, and who can read English, and who has never been convicted of a crime involving moral turpitude." In the light of the testimony given by defendant's witnesses, we find it impossible to accept such a sweeping characterization of the lack of qualifications of negroes in Morgan County. It is so sweeping, and so contrary to the evidence as to the many qualified negroes, that it destroys the intended effect of the commissioner's testimony.

In Neal v. Delaware, supra decided over fifty years ago, this Court observed that it was a "violent presumption," in which the state court had there indulged, that the uniform exclusion of negroes from juries, during a period of many years, was solely because, in the judgment of the officers, charged with the selection of grand and petit jurors, fairly exercised, "the black race in Delaware were utterly disqualified by want of intelligence, experience, or moral integrity, to sit on juries." Such a presumption at the present time would be no less violent with respect to the exclusion of the negroes of Morgan County. And, upon the proof contained in the record now before us, a conclusion that their continuous and total exclusion from juries was because there were none possessing the requisite qualifications, cannot be sustained.

We are concerned only with the federal question which we have discussed, and in view of the denial of the federal right suitably asserted, the judgment must be reversed and the cause remanded for further proceedings not inconsistent with this opinion.

Reversed.

Source: 294 U.S. 587, 1935 available online at www.law.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/FTrials/scottsboro/SB_norus.html. (Document 5.10.14)

Instruct students to work individually to create a plan for a memorial to honor the victims of lynching and to contemplate the lasting impact of lynching for Black Americans. For inspiration, have students read about the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, founded by the Equal Justice Initiative. Consider showing the short video “Why Build a Lynching Memorial?” to introduce the project.

Students should create the final memorial, either as a diorama, a blueprint, or a model. The students should also write a newspaper article to introduce the memorial to the public, explaining their choices and using research about lynching to support their decisions. Have students take turns sharing their memorials with the class, explaining the meaning behind their choices and what each aspect of the memorial signifies.

Have students take turns to read Langston Hughes’s poem “Scottsboro” aloud for the class. Discuss the students’ interpretations of the poem.

Then have students write their own poems, either individually or in pairs, inspired by what they know of the Scottsboro case. Lead a sharing session in which students read their poems for the class.

During the 1920s, Langston Hughes was one of the most well-known and influential literary figures from the Harlem Renaissance. His poetry, plays, short stories and novels reflected the experiences of African Americans of his time. In response to the Scottsboro case he wrote a play and several poems, including “Scottsboro.”

Scottsboro

8 BLACK BOYS IN A SOUTHERN JAIL

WORLD, TURN PALE!

8 black boys and one white lie.

Is it much to die?

Is it much to die when immortal feet

March with you down Time's street,

When beyond steel bars sound the deathless drums

Like a mighty heart-beat as they come?

Who comes?

Christ,

Who fought alone

John Brown.

That mad mob

That tore the Bastile down

Stone by stone.

Moses.

Jeanne d'Arc.

Dessalines.

Nat Turner.

Fighters for the free.

Lenin with the flag blood red.

(Not dead! Not dead!

None of those is dead.)

Gandhi.

Sandino.

Evangelista, too.

To walk with you --

8 BLACK BOYS IN A SOUTHERN JAIL

WORLD, TURN PALE!

Source: Hughes, Langston. Scottsboro Limited, Four Poems and a Play in Verse. New York: Golden Stair Press, 1932. (Document 5.10.15)

www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/scottsboro/filmmore/ps_hughes.html

Please login or sign up to access the student view functions.