Unit

Years: 1864-1872

Freedom & Equal Rights

Historical Events, Movements, and Figures

Prior to this lesson, students should be familiar with the history of enslavement in the United States and the ideology of White supremacy that was used to justify enslaving Black people. Furthermore, students should have some knowledge of the Civil War, including the causes and aims of the war, and the Emancipation Proclamation. Additionally, students should be familiar with levels of government (federal/ state) and the role of Congress in enacting legislation.

Charged with providing relief to destitute Southerners and helping formerly enslaved people become self-sufficient, the Freedmen’s Bureau represented a remarkable initiative on the part of the Federal government to intervene in the lives of private citizens. It was restrained in its capacity to aid the freedpeople by the politics of race, as well as by contemporary economic and social ideology, which stressed the need for the central government to maintain only the most minimal impact on the lives of individuals.

During the Civil War and Reconstruction, the federal government intervened in the lives of individual Americans in ways unthinkable before the war. From the personal income tax of wartime to the civil rights acts of the Reconstruction period, the Union toyed with governmental innovations for two reasons: to win the war, and to secure a just peace. Of all these experiments, none may be called more revolutionary than the establishment of a new agency known as the Freedmen’s Bureau.

The origins of the Freedmen’s Bureau lay in the efforts of African Americans themselves to become free. As Union troops slowly penetrated the Confederacy, enslaved African Americans ran to Union lines, requesting relief and offering service. Federal generals and policymakers confronted the dilemma created by their military success: what would happen to the territories conquered by the Union army, and to those who had been living on them? The question became particularly urgent once Union success and federal policies led to widespread emancipation.

Well before the war was won, the federal government recognized the scale of the challenge posed by the prospect of millions of newly freed African Americans. In 1863, the War Department formed the American Freedmen’s Inquiry Commission, which was composed of three prominent antebellum abolitionists and reformers. The Commission argued for the creation of a government “Emancipation Bureau,” which would oversee the transition to freedom. The Commission also urged the government to grant the freedmen full civil rights, including the right to vote. Finally, it argued that lands confiscated from rebel planters should be distributed to the freedpeople, so they could become economically self-sufficient.

Not until March of 1865, with the war nearly won, did Congress establish a government agency of the type the Commission suggested. The new agency was called the Bureau for Freedmen, Refugees, and Abandoned Lands, but was commonly known as the Freedmen’s Bureau. Its first and only Commissioner was General Oliver Otis Howard, a graduate of Bowdoin College and wartime Union commander. Howard, though sympathetic to the plight of the freedpeople, believed fervently that the Bureau was only a temporary expedient with a very limited role. Seeking to quell criticism of the Bureau, he said: “A man who can work has no right to support by government. No really respectable person wishes to be supported by others.”

The first task of the Freedmen’s Bureau was one of simple relief. The southern economy was in shambles, its systems of credit and finance ruined. Its labor system—slavery—had been abolished. Nearly everyone believed the freedpeople were incapable of functioning effectively in a market economy without “instruction.” The Freedmen’s Bureau was the government’s attempt to reconstruct the southern economy. Many thousands, both White and Black, were left homeless and destitute by the war. The disruption of agricultural production left others dangerously close to starvation. Bureau officers throughout the South spent a good deal of their time distributing food rations and clothing to displaced southern refugees, Black and White alike. Through July of 1866, the Bureau issued over 13 million rations, most to African Americans. In addition, it supplied medical care to over half a million patients by 1869.

The second undertaking of the Bureau was education for the freedpeople. By 1869, the Bureau had coordinated the establishment of over 3,000 free public schools in which 150,000 students enrolled. Chronically understaffed, the Bureau most frequently supplied the buildings for these schools, while northern missionary associations supplied the teachers. Education was the most lasting legacy of the Freedmen’s Bureau; Bureau schools led to the creation of normal schools to train teachers, as well as the great historically Black colleges of Fisk, Howard, and Hampton.

A final and most important realm of Bureau activity lay in the administration of southern lands. Throughout the South during and shortly after the war, hundreds of thousands of acres of farmland lay vacant, abandoned by owners or destroyed by marching armies. Initially, the freedpeople and their supporters had hoped that some of this land might become their own. Advocates of land distribution argued that land confiscated from former Confederates would secure for the freedpeople a basis for independent living, and protection from their former enslavers. Some early measures – such as General William Tecumseh Sherman’s Field Order Number 15, which granted lands abandoned by Georgia planters to Black residents – seemed to suggest that widespread land distribution might become a reality.

But this was not to be. A lenient program of political amnesty combined with the innate conservatism of American society served to deny the freedpeople their own land. In the White House and halls of Congress, the nation’s leaders upheld the sanctity of private property at the cost of the freedpeople’s economic independence. Wartime measures to settle Black people on abandoned land were rolled back, forcing the freedpeople to seek contracts as tenant laborers or sharecroppers. In its role as mediator between former enslaver and formerly enslaved, the Bureau accomplished some of its most important work. Bureau officers, often culled from the ranks of the Union army, oversaw the creation of thousands upon thousands of labor contracts.

Modern audiences may easily criticize the Bureau for its failings – in particular its failure to secure land distribution to the freedpeople. Yet during its brief and fragile tenure, the Bureau came under constant attack from the forces of conservatism. Opponents raised concerns about the federal government intervening between Black and White Southerners, suggested that Bureau practices disincentivized work, and expressed suspicions about the motivations and ability of Bureau agents. If the Bureau failed to do all that it might have to secure a meaningful freedom for the formerly enslaved, it was not because a better vision of freedom did not exist, but because the political system failed to put such a vision in place.

Primary Sources: The Freedmen’s Bureau, The National Archives

Primary Sources: The Freedmen’s Bureau Records, National Museum of African American History & Culture

Freedmen and Southern Society Project, University of Maryland

The Freedmen’s Colony of Roanoke Island, National Park Service

Teaching Activities: Reconstruction Period: 1865-1876, Zinn Education Project

Videos & Lesson Plans: The Reconstruction Era and the Fragility of Democracy, Facing History and Ourselves

Book: Collier, Christopher. Reconstruction and the Rise of Jim Crow, 1864-1896. New York: Benchmark, 2000

Book: Foner, Eric. Reconstruction (Updated Edition): America’s Unfinished Revolution 1863–1877. New York: Harper Collins, 2014.

Book: Cimbala, Paul A. and Randall M. Miller, eds. The Freedmen’s Bureau and Reconstruction. New York: Fordham University Press, 1999.

Many primary source documents of this time period contain references to “negro” or “negroes.” It is important to clarify that students should be mindful with language that they use to discuss the past, when terms differ from what is most appropriate to use today. You may find the Racial and Ethnic Identity guide from APA to be a helpful tool for your own reference when introducing different terms.

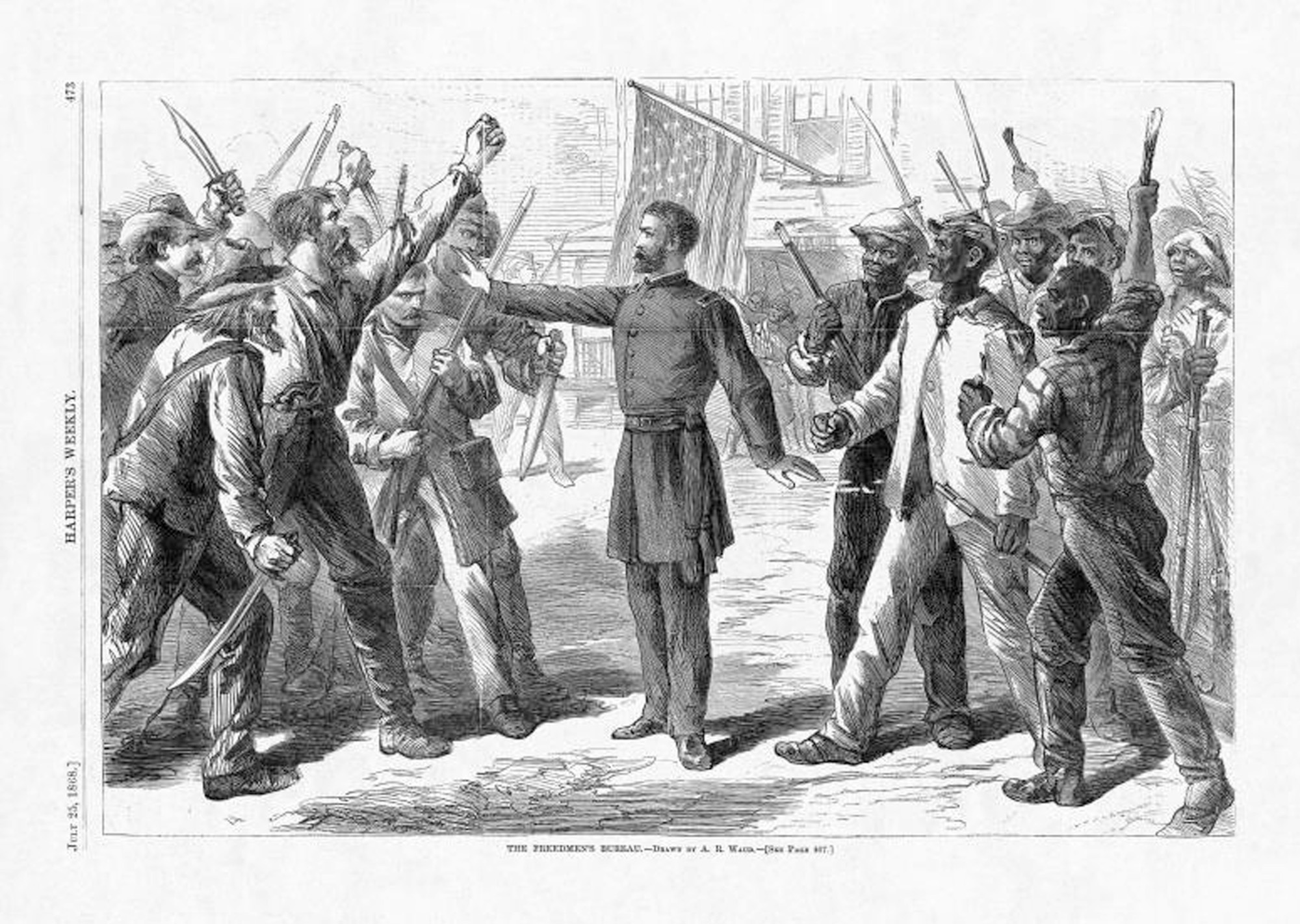

Several of the sources included in this lesson also include racist messages, both overt racist caricatures and more subtle stereotypes and paternalistic messages. These historical expressions of racism are included in order to help students recognize and understand the ongoing influence of White supremacist ideology after enslavement. However, it is imperative that these be shared with students with great care, as they can trigger painful emotions in students, such as anger, sadness, fear, and shame. African American students may feel that their identity is under attack. Moreover, if not examined critically, these sources can perpetuate anti-Black ideas. Use the guidelines below when sharing racist content with students.

During the Civil War and Reconstruction, the government of the United States intervened in the lives of individual Americans in ways that were unimaginable before the war. They did this for two reasons: to win the war and to ensure a fair and just peace. One of the most revolutionary actions taken by the government during this time was the creation of a new agency called the Freedmen’s Bureau.

Even before the war was won, the federal government recognized the challenge posed by the millions of newly freed African Americans. As Union troops made their way into Confederate territory, enslaved African Americans sought them out, seeking help and offering their services. This created a dilemma for the federal generals and policymakers: What should happen to the territories that the Union army conquered and the people who lived on them?

As the war came to an end, the southern economy was in ruins. Its labor system—slavery—had been abolished. It was widely believed that the freedpeople would struggle to participate effectively in a market economy without proper education. In March 1865, with the war almost over, Congress stepped in to provide government assistance, establishing the Bureau for Freedmen, Refugees, and Abandoned Lands, commonly known as the Freedmen’s Bureau.

The first task of the Freedmen’s Bureau was to provide relief. The war had left many people homeless and destitute. Agricultural production had been disrupted, leaving people close to starvation. Bureau officers spent a significant amount of time distributing food and clothing to displaced southern refugees, White and Black alike. By July 1866, the Bureau had provided over 13 million rations, with most going to African Americans. It also supplied medical care to over half a million patients by 1869.

Another important responsibility of the Bureau was to provide education for the freedpeople. By 1869, the Bureau had helped establish more than 3,000 free public schools with around 150,000 students enrolled. The Bureau often supplied the buildings for these schools, while northern missionary associations provided the teachers. Education became the most enduring legacy of the Freedmen’s Bureau, leading to the establishment of teacher training schools and prominent historically Black colleges such as Fisk, Howard, and Hampton.

The Bureau’s largest role was overseeing the transition from an economy based on slavery to a market economy, in which the freedpeople would participate voluntarily. The Bureau mediated between the freedpeople and their former enslavers, negotiating labor contracts. The Bureau also managed farmland in the South that had been abandoned by owners or destroyed by military forces. These lands were the source of much debate focused on whether they should be distributed to the freedpeople or returned to the White landowners.

Select the activities and sources you would like to include in the student view and click “Launch Student View.”

It is highly recommended that you review the Teaching Tips and sources before selecting the activities to best meet the needs and readiness of your students. Activities may utilize resources or primary sources that contain historical expressions of racism, outdated language or racial slurs.

To engage in Reading With a Pen, students will read three documents related to the establishment and work of the Freedmen’s Bureau:

Students can use the Reading with a Pen notetaker to keep track of information related to these two guiding questions:

After reading, bring the class back together to share what they learned about the establishment and work of the Freedmen’s Bureau.

The act establishing the Freedmen’s Bureau began life in March of 1864, as a bill in Congress to establish a Bureau of Freedmen in the War Department. Debate in Congress swirled for a year, with a plan for a permanent Bureau scuttled as too radical. Finally, in March of 1865, Congress passed the following act, establishing a temporary agency with a general mandate to aid the freedpeople.

An Act to establish a Bureau for the Relief of Freedmen and Refugees.

Be it enacted . . . That there is hereby established in the War Department, to continue during the present war of rebellion, and for one year thereafter, a bureau of refugees, freedmen, and abandoned lands, to which shall be committed, as hereinafter provided, the supervision and management of all abandoned lands, and the control of all subjects relating to refugees and freedmen from rebel states. . . .

The Secretary of War may direct such issues of provisions, clothing, and fuel, as he may deem needful for the immediate and temporary shelter and supply of destitute and suffering refugees and freedmen and their wives and children, under such rules and regulations as he may direct.

The commissioner, under the direction of the President, shall have authority to set apart, for the use of loyal refugees and freedmen, such tracts of land within the insurrectionary states as shall have been abandoned, or to which the United States shall have acquired title by confiscation or sale, or otherwise, and to every male citizen, whether refugee or freedman, as aforesaid, there shall be assigned not more than forty acres of such land, and the person to whom it was so assigned shall be protected in the use and enjoyment of the land for the term of three years. . . . At the end of said term, or at any time during said term, the occupants of any parcels so assigned may purchase the land and receive such title thereto as the United States can convey, upon paying therefor the value of the land, as ascertained and fixed for the purpose of determining the annual rent aforesaid.

APPROVED, March 3, 1865.

Source: U.S., Statutes at Large, Treaties, and Proclamations of the United States of America, vol. 13 (Boston, 1866), 507-9.

Document 4.9.3: Excerpts from The First Freedman’s Bureau Act, 1865.

General Oliver Otis Howard, head of the Freedmen’s Bureau, sent the following instructions to his Assistant Commissioners in the South during the summer of 1865, just as the war was ending. These regulations directed the work of Bureau agents throughout the South, though there was no guarantee that individual agents would follow them to the letter. Just as important as revealing the intended work of agents, the document illustrates the principles underlying the Bureau’s efforts: racial justice, economic liberalism, and a swift end to government support.

Relief establishments will be discontinued as speedily as the cessation of hostilities and the return of industrial pursuits will permit. Great discrimination will be observed in administering relief, so as to include none that are not absolutely necessitous and destitute. Every effort will be made to render the people self-supporting. Government supplies will only be temporarily issued to enable destitute persons speedily to support themselves. . . .

In all places where there is an interruption of civil war, . . . the control of all subjects relating to refugees and freedmen being committed to this bureau, the Assistant Commissioners will adjudicate . . . all difficulties arising between negroes themselves, or between negroes and whites or Indians. . . .

Negroes must be free to choose their own employers, and be paid for their labor. Agreements should be free, bona fide acts, approved by proper officers, and their inviolability enforced on both parties. The old system of overseers, tending to compulsory unpaid labor and acts of cruelty and oppression is prohibited.

Source: House Ex. Doc., no. 11, 39 Cong., 1 Sess., p. 45. In Walter Fleming, ed. Documentary History of Reconstruction (Cleveland: Arthur H. Clark, 1906), I, 328-30.

Document 4.9.5: Excerpts from “Rules and Regulations for Assistant Commissioners,” 1865

This contract represents a typical arrangement between Black laborers and a White planter during the early years of Reconstruction. In it, the workers are paid wages, rather than with the proceeds of a share of the crop. The Freedmen’s Bureau agent who oversaw the negotiation of this contract likely helped the freedpeople earn more in wages than they would have without his help.

Bureau R. F. & A. L.

Office Asst. Comr. State Office

Augusta, Ga.

March 13, 1866

State of Georgia

Wilkes County

This agreement entered into this the 9th day of January 1866 between Clark Anderson & Co. of the State of Mississippi, County of (blank) of the first part and the Freedmen whose names are annexed of the State and County aforesaid of the second part.

Witnesseth that the said Clark Anderson & Co. agrees to furnish to the Freed Laborers whose names are annexed quarters, fuel and healthey rations. Medical attendance and supplies in case of sickness, and the amount set opposite their respective names per month during the continuation of this contract paying one third of the wages each month, and the amount in full at the end of the year before the final disposal of the crop which is to be raised by them on said Clark Anderson & Co. Plantation in the County of (blank) and State aforesaid. The said Clark Anderson & Co. further agree to give the female laborers one half day in each week to do their washing &c.

The Laborers on their part agree to work faithfully and diligently on the Plantation of the said Clark Anderson & Co. for six days in the week and to do all necessary work usually done on a plantation on the Sabbath, . . . that we will be respectful and obedient to said Clark Anderson & Co. or their agents, and that we will in all respects endeavor to promote their interests, and we further bind ourselves to treat with humanity and kindness the stock entrusted to our care and will be responsible for such stock as die through our inhumanity or carelessness and we further agree to deduct for time lost by our own fault one dollar per day during the Spring and two dollars during cotton picking season, also that the Father & Mother should pay for board of children, also for lost time by protracted sickness and we further agree to have deducted from our respective wages the expense of medical attendance and supplies during sickness.

The names of 169 workers follow, including 56 adult men, 44 adult women, 61 children, and 8 hands listed as “unserviceable” (due to pregnancy or illness). The list includes the name, age, and wages due (from $5-$15) each worker.

Source: Records of the Assistant Commissioner for the State of Georgia, Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen and Abandoned Lands, 1865 _ 1869, National Archives Publication M798 Roll 36, "Unbound Miscellaneous Papers."

Document 4.9.6: A Bureau Contract, 1866

Historically Black Colleges and Universities, now known as HBCUs, are an integral part of the educational experience for countless Black Americans in modern day America. Though the Freedmen’s Bureau had its faults, its role in education and the establishment of historically black colleges are enduring legacies.

The work of the Freedmen’s Bureau in education was visible through the Morrill Acts.

Students will select and independently research a HBCU. They will then write up a summary of the school’s history that could be used to recruit new students:

The summary should include:

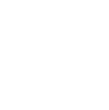

Have students examine the two political cartoons about the Freedmen’s Bureau and analyze the artists’ messages. “The Freedmen’s Bureau,” drawn by Alfred Waud for Harper’s Weekly, depicts the Bureau positively, while “The Freedmen’s Bureau!” broadside depicts it negatively, using racist imagery and stereotypes. It is imperative that the racist image be shared with students with great care. Be sure to read the Teacher Tips for suggestions on teaching with racist primary source content.

Students can use the Political Cartoon Analysis – Student Handout.

Bring the class back together to discuss:

Have students read the two later reflections on the Freedmen’s Bureau (excerpts from “The Freedman’s Bureau,” by W.E.B. Du Bois, 1901 and excerpts from The Tragic Era, by Claude G. Bowers, 1929) as homework or together in class. The Bowers excerpts contain racist, paternalistic ideas. Refer to the Teacher Tips section for guidance on how to address racist content with students.

Students can use the Analyze a Written Document tool to guide their reading. Ask students to look up more background on each author. You may wish to provide background information for students to read, or you may assign this task to students as preparation for the assignment. Based on this background information, have students make some conjectures about why these men might have written about the Bureau in the ways they did.

Working in groups, students should use the Compare and Contrast Chart or a Venn Diagram to identify common ideas as well as specific points of difference between the two sources. Show where the dispute is (i.e., what exactly does DuBois say, what exactly does Bowers say?) What kind of information would be necessary to settle the dispute? Where could this information be found (what kinds of sources)?

Finally, as a class, read what your history textbook or another recent secondary source has to say about the Freedmen’s Bureau. As a class, discuss:

Claude G. Bowers (1878–1958) was a writer, editor, and newspaper man from Indiana. He wrote popular history, producing best-sellers on the Founding Fathers. In 1929, he took on the history of Reconstruction, an effort which resulted in The Tragic Era. The book reflected two important currents of the day. The first was Populism, a political movement of the late nineteenth century which sought to empower farmers and working-class White people. The other was White supremacy. Bowers’s interpretation of Reconstruction recapitulated the commonly-held wisdom of the day – that Reconstruction had been a scandalous experiment during which Radical Republicans sought to circumvent democracy, and solidify their political hold over the nation by enfranchising Black people and using them as their puppets.

Meanwhile[, in spring of 1866] the Senate was brilliantly debating Trumbull’s bill continuing the Freedmen’s Bureau indefinitely, extending its operations to freedmen everywhere, authorizing the allotment of forty-acre tracts of the unoccupied lands of the South to negroes, and arming the Bureau with judicial powers to be exercised at will. Trumbull and Fessenden bore the brunt of the defense, and Hendricks, leading the attack, assailed the judicial feature, the extension of the Bureau’s power throughout the country, and the creation of an army of petty officials. “Let the friends of the negroes be satisfied to treat them as they are treated in Pennsylvania . . . in Ohio . . . everywhere where people have maintained their sanity upon the question,’ said Cowan of Pennsylvania.

With some moved by a sincere interest in the freedmen’s welfare, the average politician was thinking of the tremendous engine for party in the multitude of paid petty officials swarming over the South, for its possibilities had been tested. It was a party measure, and as such it was passed.

While still pending in Congress, the bill had been carefully studied in Administration circles and found “a terrific engine . . . a governmental monstrosity.” Such was the opinion of [President Andrew] Johnson, who calmly prepared to meet it with a veto. . . . In tense excitement, and a little dazed, the Senate sat listening to the Message. Merciless in its reasoning, simply phrased, there was no misunderstanding its meaning.

The Bureau’s life had not expired; why pass the bill at all? it asked. And no juries in times of peace! No indictment required! No penalty stipulated beyond the will of members of the court-martial! No appeal! No write of error in any court! “I cannot reconcile a system of military jurisdiction of this kind with the Constitution,” said the President.

Where in the Constitution is authority to expend public funds to aid indigent people? Where the right to take the white man’s land and give it to others without “due process of law”? More: the granting of so much power over so many people through so many agents would enable the President, “If so disposed, to control the action of this numerous class and use them for attainment of his own political ends.” The Message closed with the Johnsonian proposition that with eleven States excluded from Congress, the bill involved “taxation without representation.”

The next day . . . the vote was taken, and the veto sustained. A prolonged hissing in the colored galleries, some cheers in the others, and the visitors were expelled. . . .But great crows with a band of music celebrated in front of the Willard, listening to the orators praising Johnson, and the “New York Tribune” declared that “the copperheads at their homes were firing guns in honor of the presidential veto.” . . .

The day after the failure of the Freedmen’s Bureau Bill, a new measure was introduced. . . . The second Freedmen’s Bureau Bill was pushed to passage, and Johnson returned it with a veto more powerful than the first. Many Republicans were sadly shaken, and it required vigorous application of the party’s whip to force them into line, but they yielded, and the measure passed over the veto. . . .

Left to themselves, the negroes would have turned for leadership to the native whites, who understood them best. This [to the Radicals] was the danger. Imperative, then, that they should be taught to hate — and teachers of hate were plentiful. Many of these were found among the agents of the Freedmen’s Bureau, and these, paid by the Government, were devoting themselves assiduously to party organization on government time.

Over the plantations these agents wandered, seeking the negroes in their cabins, and halting them at their labors in the fields, and the simple-minded freedmen were easy victims of their guile. One of the State Commissioners of the Bureau assembled a few blacks behind closed doors in a negro’s hut, and in his official capacity informed them that the Government required their enrollment in political clubs. Thus the Bureau agents did not scruple to employ coercion.

Source: Claude G. Bowers, The Tragic Era: The Revolution after Lincoln (Cambridge, MA: Riverside, 1929), 101-3, 115, 198. (Item 4.9.B)

William Edward Burghardt DuBois was born in 1868 Great Barrington, Massachusetts. He attended college at Fisk in Nashville, Tennessee, before moving on to Harvard, where he earned a master’s degree, and the University of Berlin, where he garnered a doctorate. In his day, he was the most important student of the “race problem,” and he wrote about it all his life. He first burst onto the American literary scene with this essay in The Atlantic from 1901, during which he sought to resurrect the reputation of the Freedmen’s Bureau. He followed up this effort with The Souls of Black Folk and the monumental Black Reconstruction. Throughout his life he was active in a wide variety of political efforts to redress the race problem, from pan-Africanism, to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, to the Communist Party. Still, his efforts to reconstruct Black history proved the major component of his life’s work, and the most important of his many legacies.

No sooner had Northern armies touched Southern soil than this old question, newly guised, sprang from the earth,—What shall be done with slaves? . . . At last there arose in the South a government of men called the Freedmen's Bureau, which lasted, legally, from 1865 to 1872, but in a sense from 1861 to 1876, and which sought to settle the Negro problems in the United States of America. . . .

Thus did the United States government definitely assume charge of the emancipated Negro as the ward of the nation. It was a tremendous undertaking. Here, at a stroke of the pen, was erected a government of millions of men,—and not ordinary men, either, but black men emasculated by a peculiarly complete system of slavery, centuries old; and now, suddenly, violently, they come into a new birthright, at a time of war and passion, in the midst of the stricken, embittered population of their former masters. . . .

The very name of the Bureau stood for a thing in the South which for two centuries and better men had refused even to argue,—that life amid free Negroes was simply unthinkable, the maddest of experiments. The agents which the Bureau could command varied all the way from unselfish philanthropists to narrow-minded busybodies and thieves; and even though it be true that the average was far better than the worst, it was the one fly that helped to spoil the ointment. . . .

So the cleft between the white and black South grew. Idle to say it never should have been; it was as inevitable as its results were pitiable. Curiously incongruous elements were left arrayed against each other: the North, the government, the carpetbagger, and the slave, here; and there, all the South that was white, whether gentleman or vagabond, honest man or rascal, lawless murderer or martyr to duty. . . .

Such was the work of the Freedmen's Bureau. To sum it up in brief, we may say: it set going a system of free labor; it established the black peasant proprietor; it secured the recognition of black freemen before courts of law; it founded the free public school in the South. On the other hand, it failed to establish good will between ex-masters and freedmen; to guard its work wholly from paternalistic methods that discouraged self-reliance; to make Negroes landholders in any considerable numbers. Its successes were the result of hard work, supplemented by the aid of philanthropists and the eager striving of black men. Its failures were the result of bad local agents, inherent difficulties of the work, and national neglect. . . .

Such an institution, from its wide powers, great responsibilities, large control of moneys, and generally conspicuous position, was naturally open to repeated and bitter attacks. . . . The most bitter attacks on the Freedmen's Bureau were aimed not so much at its conduct or policy under the law as at the necessity for any such organization at all. . . .

That such an institution was unthinkable in 1870 was due in part to certain acts of the Freedmen's Bureau itself. It came to regard its work as merely temporary, and Negro suffrage as a final answer to all present perplexities. The political ambition of many of its agents and proteges led it far afield into questionable activities, until the South, nursing its own deep prejudices, came easily to ignore all the good deeds of the Bureau, and hate its very name with perfect hatred. So the Freedmen's Bureau died, and its child was the Fifteenth Amendment.

The passing of a great human institution before its work is done, like the untimely passing of a single soul, but leaves a legacy of striving for other men. . . . For this much all men know: despite compromise, struggle, war, and struggle, the Negro is not free. . . . In the most cultured sections and cities of the South the Negroes are a segregated servile caste, with restricted rights and privileges. Before the courts, both in law and custom, they stand on a different and peculiar basis. Taxation without representation is the rule of their political life. And the result of all this is, and in nature must have been, lawlessness and crime. That is the large legacy of the Freedmen's Bureau, the work it did not do because it could not.

Source: W. E. B. DuBois, “The Freedmen's Bureau,” Atlantic Monthly 87 (1901), 354-65. (Item 4.9.C)

If unfamiliar with the pedagogical approaches below, teachers should review the Opinion Continuum overview in advance of the activity.

Part 1: Read & Analyze

Inform students that Congress originally only authorized the Freedmen’s Bureau to operate for a period of one year from the end of the Civil War. Thus, in the spring of 1866, Congress had to determine whether to reauthorize the agency for it to continue functioning. At that point, the transition to free labor had just begun, and an economic downturn was making the shift all the more challenging. Tell students that there were various perspectives on the Freedman’s Bureau, and deciding whether to extend it was a contentious topic.

Assign students individually or in pairs to one of the documents relating to the Freedman’s Bureau. If you do not end up using all the documents, make sure that the documents assigned represent the full range of Conservative, Moderate, and Radical viewpoints. Be sure to prepare students to encounter paternalistic ideas.

Students should read and analyze the documents, using the written document analysis tool.

Part 2: Opinion Continuum

Ask students whether the author of the source they read would have supported renewing the Freedmen’s Bureau. If more than one student reads the same source, give them time to discuss and come to agreement on the author’s perspective.

In order to create a continuum, to reflect the range of opinions in this collection of primary sources, and to provide a kinesthetic and visual learning opportunity, students will move to reflect their opinions. Designate the space where students will line up, and identify the two ends of the continuum, as “Yes, definitely” and “Definitely not” on the question of whether the Freedmen’s Bureau should continue. Direct students to line up based on the perspective expressed in the source that they read. Students may stand anywhere between the two extremes, in accordance with the viewpoints expressed in the source.

Once students have lined up, call on students at different points along the continuum to articulate the viewpoint and arguments contained in the document that they read. Be sure that students understand that they are not adopting that viewpoint as their own. They should begin their statement by identifying the author of the document. Students may change their location in the continuum, if they realize that their source’s point of view is more or less extreme than other points of view.

Part 3: Create a Research Agenda

Either in a discussion, or as a written activity, ask students to respond to the following questions:

J.D.B. De Bow was a wealthy and prominent southerner who lived through the Civil War years. He published DeBow’s Review, an influential journal, out of New Orleans, Louisiana. DeBow’s Review offered a conservative slant on the problems of Reconstruction, often echoing the paternalism of the southern White elite. DeBow offered the following testimony before Congress in 1866.

I think if the whole regulation of the negroes, or freedmen, were left to the people of the communities in which they live, it will be administered for the best interest of the negroes as well as of the white men. I think there is a kindly feeling on the part of the planters towards the freedmen. They are not held at all responsible for anything that has happened. They are looked upon as the innocent cause.

In talking with a number of planters, I remember some of them telling me they were succeeding very well with their freedmen, having got a preacher to preach to them and a teacher to teach them, believing it was for the interest of the planter to make the negro feel reconciled; for, to lose his services as a laborer for even a few months would be very disastrous. The sentiment prevailing is, that it is for the interest of the employer to teach the negro, to educate his children, to provide a preacher for him, and to attend to his physical wants. . . .

The Freedmen’s Bureau, or any agency to interfere between the freedman and his former master, is only productive of mischief. There are constant appeals from one to the other and continual annoyances. It has a tendency to create dissatisfaction and disaffection on the part of the laborer, and is in every respect in its result most unfavorable to the system of industry that is now being organized under the new order of things in the South.

Source: Report of the Joint Committee on Reconstruction, part iv, p. 134. (Document 4.9.7)

A Confederate cavalry officer and later general, Wade Hampton (1818-1902) was one of South Carolina’s most prominent planters. He ran for Governor of South Carolina and lost a close election to James Lawrence Orr in 1865. At the end of the Radical phase of Reconstruction, in 1876, he ran again as a Democrat, against incumbent Republican Daniel Chamberlain. The election was so close that South Carolina had two governors for a short time, until President Ulysses S. Grant withdrew Federal troops from South Carolina, thus conceding the election to Hampton, and ending Reconstruction in South Carolina. Hampton prepared the following report of conditions in the South for President Andrew Johnson in 1866.

The strong but paternal hand which had controlled him [i.e., “the negro”] through centuries of slavery, having been suddenly and rudely withdrawn, the only hope of rendering him either useful, industrious or harmless, was to elevate him in the scale of civilization, and to make him appreciate not only the blessings, but the duties of freedom. This was the prevalent . . . sentiment of the South. . . .

That much more had not been done to carry this sentiment into effect is due solely to the pernicious and mischievous inference of that most vicious institution, the Freedmen’s Bureau. . . . The whole machinery of this bureau has been used by the basest men, for the purpose of swindling the negro, plundering the white man and defrauding the Government.

There may be an honest man connected with the Bureau, but I fear that the commissioners sent by your Excellency to probe the rottenness of this cancer will find their search for such as fruitless as was that of the Cynic of old. The report of these Commissioners furnishes ample justification for the ill-will, the distrust, and the contempt with which the people of the South regard this baleful and pernicious institution.

Source: Wade Hampton to Andrew Johnson, 1866, in Walter Fleming, ed. Documentary History of Reconstruction (Cleveland: Arthur H. Clark, 1906), I, 368-69. (Document 4.9.8)

In 1871, Congress began an intensive investigation into the activities of the Ku Klux Klan throughout the South. Concerned that the Klan was denying freedpeople their civil rights, Republicans in Congress heard testimony from hundreds of southerners, White and Black, conservative and radical. The resulting transcripts offer a wealth of information on southern life during the Reconstruction. The following testimony of an Alabama planter named Daniel Taylor offers insights into the ways the Freedmen’s Bureau was perceived by many southern White planters.

The negroes that would go and settle down on plantations and work and stay there always had plenty to eat. The white men who employed them felt bound to keep them in plenty to eat and good clothes to wear when they would stay with them.

But if a man was trying to make a negro work, and talked a little short to the negro, he [the negro] would pick up and go somewhere else. . . . The negroes would quit and go off for this Bureau when they should have had a dependence in the country. They depended upon the Bureau for their rations. . . .

The negroes cheated the farmers out of their labor. . . . The negroes were to pay for their provisions out of their part of the crop and they did not go on making their crop, so that their part of the crop was not sufficient to pay the owner the amount that was due him for the land and stock and the advance.

Source: Ku Klux Klan Report, Alabama Testimony (1871), 1132. (Document 4.9.9)

General Ulysses S. Grant commanded all Union armies at the end of the Civil War. In November of 1865, President Andrew Johnson sent Grant on a tour throughout the South to observe conditions. In December, Grant sent his report to Johnson. A military man with few clear political sentiments, Grant steered toward a moderate-conservative position on the reconstruction of the South. In general, he told Johnson what he wanted to hear – that white southerners were accepting defeat and emancipation gracefully. This notion, while not generally true, buttressed Johnson’s policy of quick reconciliation with the former Confederates, and undermined the Radicals’ calls for continued intervention – militarily and otherwise – into southern affairs. As far as the freedpeople went, Grant believed white southerners were their best and natural “friends,” on whom they should first rely. He thus reflected a paternalism he shared with southern conservatives and some northern moderates alike.

In some of the States its [i.e., the Freedmen’s Bureau’s] affairs have not been conducted with good judgment or economy, and that the belief, widely spread among the freedmen of the Southern States, that the lands of their former owners will, at least in part, be divided among them, has come from the agents of this bureau. This belief is seriously interfering with the willingness of the freedmen to make contracts for the coming year. In some form the Freedmen’s Bureau is an absolute necessity until civil law is established and enforced, securing to the freedmen their rights and full protection. . . .

Many, perhaps a majority, of the agents of the Freedmen’s Bureau advise the freedmen that by their own industry they must expect to live. To this end they endeavor to secure employment for them, and to see that both contracting parties comply with their engagements. In some instances, I am sorry to say, the freedman’s mind does not seem to be disabused of the idea that a freedman has the right to live without care or provision for the future.

The effect of the belief in division of lands is idleness and accumulation in camps, towns, and cities. In such cases I think it will be found that vice and disease will tend to the extermination, or great reduction of the colored race.

It cannot be expected that the opinions held by men at the South for years can be changed in a day; and therefore the freedmen require for a few years not only laws to protect them, but the fostering care of those who will give them good counsel, and in whom they can rely.

Source: Senate Ex. Doc. No. 2, 30 Cong., 1 Sess., 117. (Document 4.9.11)

The following testimony, by General John Tarbell of the Union army, illustrates the moderate position on the Freedmen’s Bureau.

I think they [the planters] have well grounded complaints against the Freedmen’s Bureau; and I do not think their criticism upon that bureau are in every instance dictated by motives of disloyalty. I do not mean to say what proportion of the officers of that bureau are incompetent or corrupt, but that there are many such I have no doubt. In such districts there has been a good deal of complaint, and to a casual observer their comments might be ascribed, perhaps, to motives of disloyalty; but a more careful attention to the subject satisfied me that their complaints were well grounded in a great many cases, for in districts where they had upright, intelligent, and impartial officers of the bureau, the people expressed entire satisfaction. They stated to me that where they had such officers, and where they had soldiers who were under good discipline, they were entirely welcome, and indeed they were glad to have their presence – in some cases approving the action of the bureau officers in punishing white men for the ill treatment of colored people, saying that the officers were perfectly right.

In other districts, I am satisfied that it often occurred that bureau officers, wanting in good sense, would show a decided partiality for the colored people, without regard to justice. I am satisfied, also, there were districts where the planters would insure the favor of the bureau officers to them by paying them money; and while they were glad to have their favor, still they would condemn such officers, and in such districts there was dissatisfaction.

Source: Report of the Joint Committee on Reconstruction of the First Session Thirty-Ninth Congress, Government Printing Office, Washington, 1866, Georgia – Alabama – Mississippi – Arkansas, pages 155-157. (Document 4.9.12)

Born near Cologne, Germany, in 1829, Carl Schurz emigrated to Wisconsin in 1852, where he began a career as a lawyer and politician. He rose rapidly in the Republican Party, eventually supporting Abraham Lincoln’s Presidential bid in 1860. He was rewarded by being named minister to Spain, a position he left to fight in the Civil War. Lincoln made him a general, and Schurz repaid him by assisting him in his re-election campaign of 1864. After the war, President Andrew Johnson recognized Schurz’s political contributions as a moderate Republican, naming him a Special Commissioner to oversee conditions in the Gulf states. Schurz filed the following report in this capacity.

_____________________________________________________________________________________

While the Southern people are always ready to expatiate upon the shortcomings of the Freedmen’s Bureau, they are not so ready to recognize the services it has rendered. I feel warranted in saying that not one-half of the labor that has been done in the South this year or will be done there next year, would have been or would be done but for the exertions of the Freedmen’s Bureau. The confusion and disorder of the transition period would have been infinitely greater had not an agency interfered which possessed the confidence of the emancipated slaves; which could disabuse them of any extravagant notions and expectations and be trusted; which could administer to them good advice and be voluntarily obeyed.

No other agency, except one placed there by the national government, could have wielded that moral power whose interposition was so necessary to prevent the southern society from falling at once into the chaos of a general collision between its different elements.

That the success achieved by the Freedmen’s Bureau is as yet very incomplete cannot be disputed. A more perfect organization and a more carefully selected personnel may be desirable; but it is doubtful whether a more suitable machinery can be devised to secure to free labor in the South that protection against disturbing influences which the nature of the situation still imperatively demands.

Source: Senate Ex. Doc., no. 2, 39 Cong., 1 Sess, 40. (Document 4.9.13)

T.W. Conway was a chaplain in the Union Army, who served as head of the Freedmen’s Bureau in Louisiana. His tenure was not successful, and he was eventually removed. He began touring the North, speaking on the importance of the Bureau for southern blacks. This passage is taken from his testimony to Congress.

I should expect in Louisiana, as in the whole southern country, that the withdrawal of the Freedmens Bureau would be followed by a condition of anarchy and bloodshed. . . I am pained at the conviction that I have in my own mind that if the Freedmen’s Bureau is withdrawn the result will be fearful in the extreme.

What it has already done and is now doing in shielding these people, only incites the bitterness of their foes. They will be murdered by wholesale, and they in their turn will defend themselves. It will not be persecution merely; it will be slaughter; and I doubt whether the world has ever known the like.

These southern rebels, when the power is once in their hands, will stop at nothing short of extermination. Governor Wells himself told me that he expected in ten years to see the whole colored race exterminated, and that conviction is shared very largely among the white people of the south. It has been threatened by leading men there that they would exterminate the freedmen. . . . The wicked work has already commenced, and it could be shown that the policy pursued by the government is construed by the rebels as not being opposed to it.

Source: Report of the Joint Committee on Reconstruction, part iv, 82. (Document 4.9.14)

Sidney Andrews was a newspaper correspondent sympathetic with the plight of the freedpeople. In 1866, he published The South Since the War, an important commentary documenting his travels through the war-torn South. This passage from that book was read into a Congressional committee report in 1871.

Of the thousand things that the bureau has done no balance sheet can ever be made. How it helped the ministers of the church, saved the blacks from robbery and persecution, enforced respect for the negro’s rights, instructed all the people in the meaning of the law, . . . brought about amicable relations between employer and employed, corrected bad habits among white and blacks, restored order, sustained contracts for work, compelled attention to the statute books, . . . furthered local educational movements, . . . dignified labor, . . . rooted out old prejudices, . . . assisted the freemen to become land-owners, . . . set idlers at work, . . . carried the light of the North into the dark places of the South, steadied the negro in his struggle with novel ideas, . . . checked the passion of the whites and blacks, . . . assisted in creating a sentiment of nationality — how it did all this and a hundred-fold more, who shall ever tell? What pen shall ever record? . . .

Success! The world can point to nothing like it in all the history of emancipation. No thirteen millions of dollars were ever more wisely spent; yet, from the beginning of this scheme has encountered the bitterest opposition and the most unrelenting hate. Scoffed at like a thing of shame, often struck and sorely wounded, sometimes in the house of its friends, apologized for rather than defended; yet with God on its side, the Freedmen’s Bureau has triumphed; civilization has received a new impulse, and the friends of humanity may well rejoice.

The bureau work is being rapidly brought to a close, and its accomplishments will enter into history, while the unfounded accusations brought against it will be forgotten. There is a day and hour when slander lives not. When the passions of men subside, and when the dust of time has well fallen, then comes the hour of calmer judgement. Many-tongued scandal has the briefest of existence. . . . Evil is quickly forgotten; truth alone is abiding.

Source: House Report no 121, 41 Cong., 2 Sess., (1871), p. 20. (Document 4.9.15)

Begin by providing students, as needed, an overview of the historical context of Reconstruction and the establishment of the Freedmen’s Bureau in 1865. This should include the goals of the Bureau, such as providing education, legal assistance, and economic support to freed African Americans.

Provide students with the excerpted copy of the Second Freedmen’s Bureau and review the introduction together:

“It was a provision of the original act establishing the Freedmen’s Bureau that Congress would have to renew the agency for it to continue functioning. By spring of 1866 it was clear that much work remained to be done. The transition to free labor had just begun, and an economic downturn was making the shift all the more challenging. In this climate, Congress began debating the provisions under which the Freedmen’s Bureau Act would be renewed. Radical Republicans in Congress sought to enlarge its powers considerably. Their proposal called for making the Bureau a permanent fixture, strengthening its system of independent courts, and providing for liberal homesteading by blacks – the oft-cited promise of “forty acres and a mule.” To the shock of Congress, the conservative President Andrew Johnson vetoed the bill, thus causing dissent among Congressional Republicans and widening the already-present breach between Johnson and Congress. The Republicans went back to the drawing board and recrafted the bill. The Bureau’s life was extended for three years, and the homesteading provisions were removed. This revised version of the bill passed over Johnson’s veto on July 16.”

Divide students into small groups and have students analyze the document taking notes using the guided questions. Questions may include:

Reconvene as a class and facilitate a discussion based on the analysis around the economic, educational and legal freedoms affected.

Excerpts from The Second Freedman’s Bureau Act, 1866

It was a provision of the original act establishing the Freedmen’s Bureau that Congress would have to renew the agency for it to continue functioning. By spring of 1866 it was clear that much work remained to be done. The transition to free labor had just begun, and an economic downturn was making the shift all the more challenging. In this climate, Congress began debating the provisions under which the Freedmen’s Bureau Act would be renewed. Radical Republicans in Congress sought to enlarge its powers considerably. Their proposal called for making the Bureau a permanent fixture, strengthening its system of independent courts, and providing for liberal homesteading by blacks – the oft-cited promise of “forty acres and a mule.” To the shock of Congress, the conservative President Andrew Johnson vetoed the bill, thus causing dissent among Congressional Republicans and widening the already-present breach between Johnson and Congress. The Republicans went back to the drawing board and recrafted the bill. The Bureau’s life was extended for three years, and the homesteading provisions were removed. This revised version of the bill passed over Johnson’s veto on July 16.

The act to establish a Bureau for the relief of Freedmen and Refugees . . . shall continue in force for the term of two years from and after the passage of this act. . . .

The Secretary of War [may] issue such medical stores or other supplies and transportation and afford such medical or other aid as may be needful . . . Provided, that no person shall be deemed “destitute,” “suffering,” or “dependent upon the Government for support,” within the meaning of this act, who is able to find employment, and could, by proper industry and exertion, avoid such destitution, suffering, or dependency. . . .

The sales made to “heads of families of the African race,” under the instructions of President Lincoln . . . are hereby confirmed and established; and all leases which have been made to such “heads of families” . . . shall be changed into certificates of sale. . . .

The [Freedmen’s Bureau] Commissioner shall have power to seize, hold, use, lease, or sell all buildings . . . formerly held under color of title by the late so-called Confederate States, and not heretofore disposed of by the United States, . . . and to use the same or appropriate the proceeds derived therefrom to the education of the freed people. . . .

In every State or district when the ordinary course of judicial proceedings has been interrupted by the rebellion, . . . the right to make and enforce contracts, to sue, be parties, and give evidence, to inherit, purchase, lease, sell, hold, and convey real and personal property, and to have full and equal benefit of all laws and proceedings concerning personal liberty, personal security, and the acquisition, enjoyment, and disposition of estate, real and personal, including the constitutional right to bear arms, shall be secured to and enjoyed by all the citizens of such State or district without respect to race or color, or previous condition of slavery. . . .

Source: Acts and Resolutions, 39 Cong., 1 Sess., p. 191. (Document 4.9.4)

After engaging in the Political Cartoon Analysis activity, invite students to plan and draw a cartoon that directly responds to the Freedman’s Bureau! cartoon. Alternatively, students can respond to the cartoon with another creative product, such as a poem or spoken word piece.

Revisit the research agenda from Activity 4. In that activity, students were asked to identify answers to the following questions:

Students should use the agenda along with any other relevant questions from the completion of activities to complete a research project that includes an introduction with relevant background information to provide context for the research, the specific research question(s), the approach to analyzing data or sources, findings and implications for their understanding and our current socio-political context.

Please login or sign up to access the student view functions.