Unit

Years: 1929-1945

Economy & Society

Freedom & Equal Rights

Students should be familiar with the push and pull factors of the Great Migration before starting this lesson. It would also be helpful for students to have prior knowledge of the Great Depression and the New Deal, as this lesson focuses on the impact of both events on Black Americans rather than the New Deal policies as a whole. Finally, students should understand the widespread segregation and discrimination that Black Americans faced in the workforce and in the military in the early 1900s.

During World War II, Black Americans fought for freedom and democracy abroad while facing rampant inequality at home–inequality that was made worse by the Great Depression. When it became apparent that the U.S. government was content with the status quo of segregation and discrimination, Black leaders, the Black press, and the NAACP began to organize and agitate for change. Inclusion in some New Deal programs paved the way for a “Double Victory” in the war, and “Double V” became a credo that was translated into legal and legislative strategies that won real results for Black Americans.

The Great Depression and Black Americans

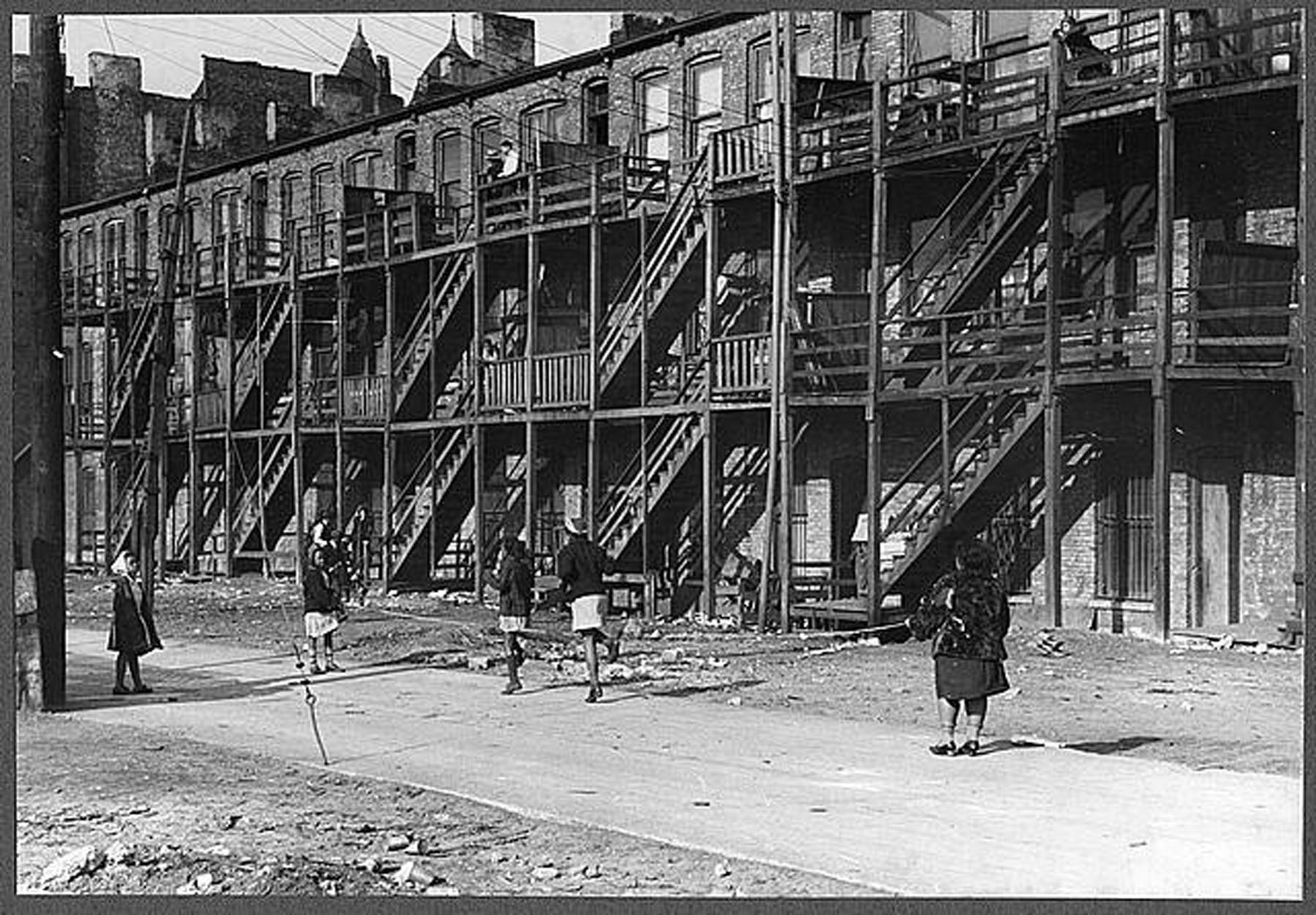

The Great Depression devastated members of all socio-economic classes in the United States. However the impact was greatest on those who were already struggling, and the greatest burden fell on Black Americans. Black Americans were the last hired and first fired from jobs. While White Americans faced soaring unemployment rates of about 25% in 1932 across Northern cities, the unemployment rate for Black workers more than doubled that, reaching 50% in Chicago and 60% in Detroit. In the South, Black sharecroppers fell into more debt to their White landlords, causing many to move to Northern cities and fueling a second wave of the Great Migration.

FDR’s New Deal

Democratic politician Franklin Delano Roosevelt ran his 1932 presidential campaign calling for a “new deal” for Americans suffering under the Great Depression. Many Black Americans saw Roosevelt as a savior, and the 1932 election marked a period of party realignment; a large percentage of Northern Black voters stopped casting their ballots for the Republican “party of Lincoln,” and became Democrats to vote for Roosevelt. (Southern Black citizens were still unable to vote due to Jim Crow laws disenfranchising them.)

However, the promise of the New Deal was elusive for Black Americans, and some of Roosevelt’s early programs actually harmed Black Americans. For example, the Agricultural Adjustment Act was a federal program that aided large farms that were mostly White owned, not small farmers or sharecroppers who were far more likely to be Black. In fact, under this act, farmers were paid not to plant, so many White farmers fired and evicted their Black sharecroppers. Roosevelt also never fought to extend voting privileges to Southern Black Americans who had no access to the ballot box. He never supported anti-lynching legislation. The New Deal was a false promise for many Black Americans.

Some of the New Deal initiatives did help Black Americans, though. Roosevelt mandated that 10% of federally funded work opportunities be given to Black Americans since that was the percentage of Blacks in the United States population. The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) and the Works Progress Administration (WPA) were noteworthy programs that both employed Black men in high numbers. The WPA especially benefited Black Americans by creating the Federal Writers Project, which collected the stories of formerly enslaved people, officially documented Black culture and history, and sponsored Black artists.

Over time the New Deal programs became more race-conscious. After First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt discovered that Blacks were discriminated against in the South’s WPA programs, she made sure that their complaints received a hearing at the White House, and in 1935, FDR signed an executive order barring discrimination in the administration of any WPA project. FDR also created a “Black Cabinet,” an advisory board to guide his initiatives that included Black political thinkers such as A. Philip Randolph and Mary Bethune. In the end, many Black voters saw the New Deal as a flawed but good deal for Black Americans.

World War II

In the midst of the Great Depression, World War II broke out. Mobilization required so many soldiers and workers that the unemployment problem quickly turned into a labor shortage. But while White workers were rapidly brought into war production, Black Americans encountered discrimination. Many AFL unions excluded Black workers, and government-sponsored job training programs did not encourage Black applicants to apply. The military did not accept Black soldiers into combat units, limiting them to menial positions. When organizations such as the NAACP and the Urban League staged mass protests, President Roosevelt “looked the other way.” Having safely won re-election in 1940, he did not want to offend southern segregationist politicians by supporting African Americans’ claims to equal rights to work and fight for their country.

Black Americans supported the war effort, but they also recognized the hypocrisy of fighting simultaneously against fascism in Europe and for equality and justice in the United States. In 1941 a young Black man sent a letter to the Pittsburgh Courier suggesting a “Double V” campaign for victory over fascism abroad and victory over racial discrimination at home. The Courier promoted this idea, and Black Americans across the country adopted the “Double V” slogan.

The Double Victory Campaign

In early 1941, union organizer A. Philip Randolph called for 100,000 Black people to march on Washington to demand a presidential order to forbid racial discrimination by companies with government contracts and to end segregation in the military. This program gained support from many African Americans who had not been involved in civil right protests before. Fearing that such a demonstration would damage America’s world-wide reputation for democracy, Roosevelt issued an Executive Order that said in part: “I do hereby affirm the policy of the United States that there shall be no discrimination in the employment of workers in the defense industry or government because of race, creed, color or national origin.” Roosevelt also created the Fair Employment Practices Commission (FEPC) with the power to investigate racial discrimination. Randolph called off the march. The policy of segregation in the military remained unchanged, however, and the Executive Order did not deal with discrimination by unions or give the FEPC adequate enforcement powers. But it signaled a promise that the federal government would protect African Americans’ employment rights.

The wartime demand for industrial workers also brought more Black Americans into the labor force. Many Black women left their traditional jobs in domestic service to take jobs in war plants; 600,000 Black women, 400,000 of whom had been domestics, shifted to industrial employment. Black workers joined unions enthusiastically; between 1940 and 1945, Black membership in labor unions jumped from 200,000 to 1.2 million. The availability of high-paying jobs in defense industries further accelerated the Great Migration.

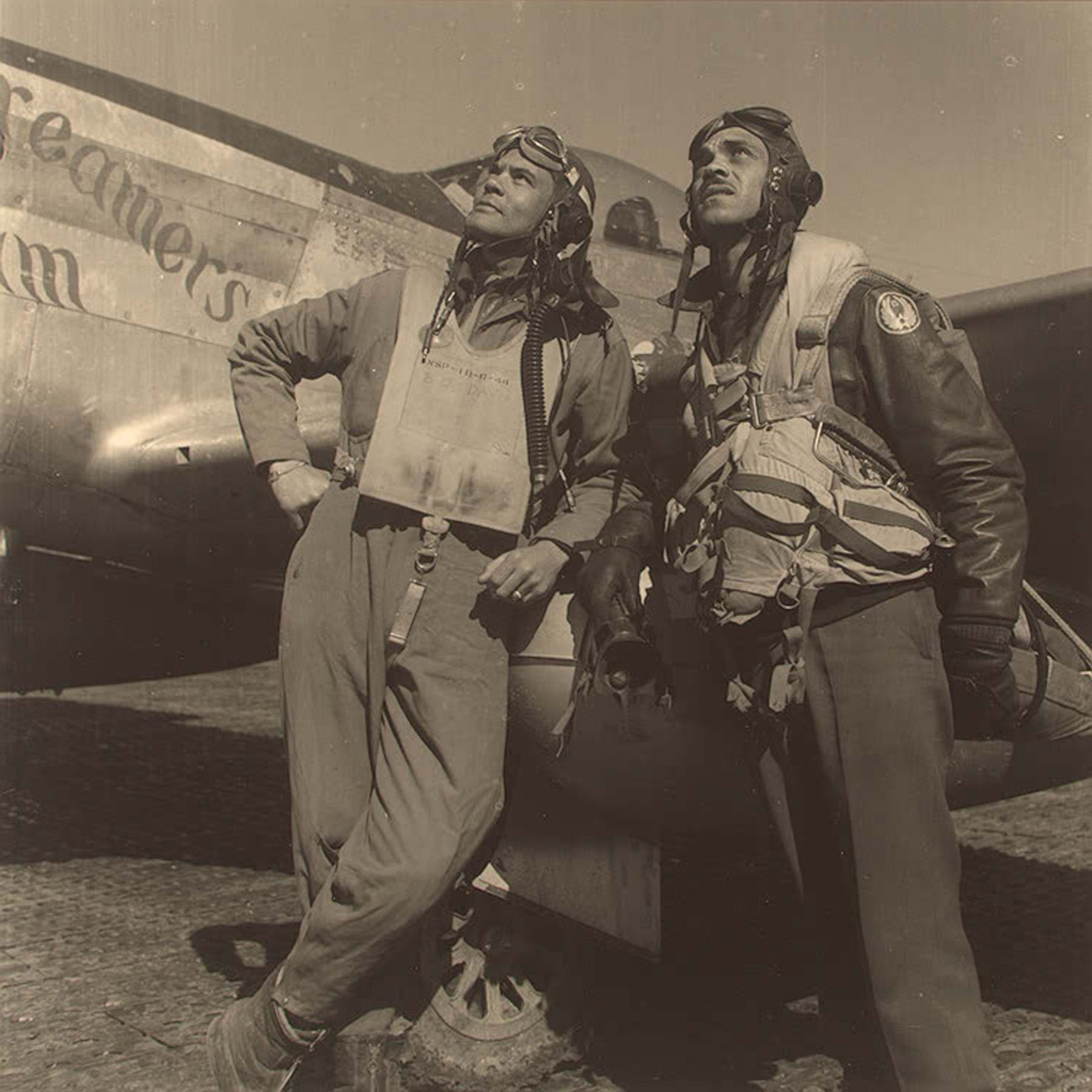

Sustained protest by the Double Victory campaign and the military’s needs also led to some changes in War Department policies. Both the Navy and the Marine Corps began to accept Black American volunteers, Black soldiers were trained as officers, and Black volunteers gradually began to engage in combat units under White officers. An all-Black airmen’s squadron in a program at Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, known as Tuskegee Airmen, completed over 1,500 attack missions and were recognized with 150 Distinguished Flying Crosses, 14 Bronze Stars, and 744 Air Medals. Black women were also given expanded opportunities with some 4,000 serving in the Women’s Auxiliary Corps. With their participation in World War II and their increasing inclusion in FDR’s America, Black Americans gained a deep sense of group solidarity and renewed strength and commitment to the promise of equality and social justice.

Anderson, Karen Tucker. “Last Hired, First Fired: Black Women Workers during World War II.” The Journal of American History, vol. 69, no. 1, 1982, pp. 82–97. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/1887753. Accessed 10 May 2023.

Bailey, Beth, and David Farber. “The ‘Double-V’ Campaign in World War II Hawaii: African Americans, Racial Ideology, and Federal Power.” Journal of Social History, vol. 26, no. 4, 1993, pp. 817–43. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3788782. Accessed 10 May 2023.

Bell, Derrick. “Diversity’s Distractions.” Columbia Law Review, vol. 103, no. 6, 2003, pp. 1622–33. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/3593396. Accessed 10 May 2023.

Cooper, Michael. The Double V Campaign: African Americans in World War II. Dutton Children’s Books, 1998.

Kersten, Andrew E. “African Americans and World War II.” OAH Magazine of History, vol. 16, no. 3, 2002, pp. 13–17. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/25163520. Accessed 10 May 2023.

Learning For Justice. “The New Deal, Jim Crow, and the Black Cabinet.” Southern Poverty Law Center. https://www.learningforjustice.org/podcasts/teaching-hard-history/jim-crow-era/the-new-deal-jim-crow-and-the-black-cabinet

Mullenbach, Cheryl. Double Victory: How African American Women Broke Race and Gender Barriers to Help Win World War II. Chicago: Chicago Review Press, 2017.

National Museum of African American History and Culture. “Double Victory: The African American Military Experience.” Smithsonian. https://nmaahc.si.edu/explore/exhibitions/double-victory

National World War II Museum. “The Double V Victory.” National World War II Museum. https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/double-v-victory

Ruffin, Herbert. “FDR’s Black Cabinet: 1933-1945.” Black Past. https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/fdrs-black-cabinet-1933-1945/

Sears, James M. “Black Americans and the New Deal.” The History Teacher, vol. 10, no. 1, 1976, pp. 89–105. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/491578. Accessed 10 May 2023.

Sitkoff, Harvard. A New Deal For Blacks: The Emergence of Civil Rights as a National Issue. New York: Oxford University Press, 2008.

Sklaroff, Lauren Rebecca. Black Culture and the New Deal: The Quest for Civil Rights in the Roosevelt Era. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009.

Takaki, Ronald. Double Victory: A Multicultural History of America in World War II. Boston: Back Bay Books, 2001.

Werner, Jansen B. “Black America’s Double War: Ralph Ellison and ‘Critical Participation’ during World War II.” Rhetoric and Public Affairs, vol. 18, no. 3, 2015, pp. 441–70. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.14321/rhetpublaffa.18.3.0441. Accessed 10 May 2023.

We recommend balancing the ways in which Black Americans experienced inequality during the Great Depression, the New Deal, and WWII with the ways in which Black Americans experienced solidarity, joy, and a flourishing culture. This is not simply a story of struggle and challenge, but also one of strength and celebration in Black identity. It’s also important to highlight the systemic–rather than the individual–nature of racism during this time period. While FDR proposed some policies intended to positively impact Black Americans, they were sometimes ineffective because of structural racism that would take decades to unravel; some of these structures remain even today. Helping students to understand how racism is embedded in political, economic, and social structures will support the learning in this lesson.

The Great Depression was devastating for nearly the entire United States, but it hit Black Americans particularly hard. When Democratic politician Franklin Delano Roosevelt (FDR) ran his 1932 presidential campaign calling for a “new deal” for Americans suffering under the Great Depression, northern Black voters were hopeful that this “new deal” would help relieve the high unemployment rates and poverty plaguing Black communities across the U.S. Some of FDR’s New Deal policies did indeed alleviate suffering; FDR mandated that 10% of federal jobs go to Black Americans, and some programs such as the Works Progress Administration (WPA) and the Federal Writers Project sought to document Black stories and sponsor Black artists. Other policies, however, actually harmed Black communities by failing to change Jim Crow laws, lynching laws, or segregation in several industries. Nevertheless, the New Deal set the stage for a broader critique of the racism embedded in American society and law.

In the midst of the Great Depression, World War II broke out. Black Americans supported the war effort, but they also recognized the hypocrisy of fighting for freedom and democracy in Europe while they experienced inequality and racism in the United States. Black Americans used this contradiction to organize a “Double Victory” campaign pushing for both victory over fascism overseas and victory over racial discrimination at home. Sustained protest by the Double Victory campaign led to more inclusion of Black soldiers in the military, more legal protectors for Black American workers, and higher Black participation in labor unions. With their participation in World War II and their increasing inclusion in FDR’s America, Black Americans gained a deep sense of group solidarity and renewed strength and commitment to the promise of equality and social justice.

Select the activities and sources you would like to include in the student view and click “Launch Student View.”

It is highly recommended that you review the Teaching Tips and sources before selecting the activities to best meet the needs and readiness of your students. Activities may utilize resources or primary sources that contain historical expressions of racism, outdated language or racial slurs.

In order to complete this Jigsaw activity, place students into small groups of 3-4 students, and assign each group one of the following New Deal programs to research.

Students should find answers to the following questions as they research their assigned program:

Then, have students share out in a mixed small group with students who researched different programs. Hold a class discussion to summarize takeaways and trends, focusing on these questions:

Students will compare two different songs, “The Ballad of Roosevelt” by Langston Hughes and “His Spirit Lives On” by Joe Williams, which were written within a few years of one another.

Students should work in pairs. Each pair reads both songs together and then completes a Venn diagram to compare and contrast the poems.

Then have a full class discussion using the following questions:

“Ballad of Roosevelt” by Langston Hughes, 1934

Langston Hughes was a composer, poet, playwright, author, journalist and all around giant of the Harlem Renaissance. He wrote about the world around him, capturing the events and sentiments that affected both America and the African American population. The jazz-influenced “Ballad of Roosevelt,” appeared in the New Republic in 1934, one year into Roosevelt’s presidency.

The pot was empty,

The cupboard was bare.

I said, Papa,

What’s the matter here?

I’m waitin’ on Roosevelt, son,

Roosevelt, Roosevelt,

Waitin’ on Roosevelt, son.

The rent was due,

And the lights was out.

I said, Tell me, Mama,

What’s it all about?

We’re waitin’ on Roosevelt, son,

Roosevelt, Roosevelt,

Just waitin’ on Roosevelt.

Sister got sick

And the doctor wouldn’t come

Cause we couldn’t pay him

The proper sum—

A-waitin on Roosevelt,

Roosevelt, Roosevelt,

A-waitin’ on Roosevelt.

Then one day

They put us out o’ the house.

Ma and Pa was Meek as a mouse

Still waitin’ on Roosevelt,

Roosevelt, Roosevelt.

But when they felt those

Cold winds blow

And didn’t have no

Place to go

Pa said, I’m tired

O’waitin’ on Roosevelt,

Roosevelt, Roosevelt.

Damn tired o’ waitin’ on Roosevelt.

I can’t git a job

And I can’t git no grub.

Backbone and navel’s

Doin’ the belly-rub—

A-waitin’ on Roosevelt,

Roosevelt, Roosevelt.

And a lot o’ other folks What’s hungry and cold

Done stopped believin’

What they been told

By Roosevelt,

Roosevelt, Roosevelt—

Cause the pot’s still empty,

And the cupboard’s still bare,

And you can’t build a

bungalow

Out o’ air—

Mr. Roosevelt, listen!

What’s the matter here?

Source: Langston Hughes, “Ballad of Roosevelt,” New Republic 31 (November 14, 1934): 9. Document 5.11.2

“His Spirit Lives On,” recorded by Joe Williams, 1945

Blues musician, Big Joe Williams’, commemoration of Roosevelt’s death in 1945 was captured in his song, “His Spirit Lives On.” Blues is another distinctly African American musical form that combines traditional African musical styles with the heartbreak of slavery, sharecropping, and prejudice. Blues embrace rhythm and tell a story.

Well you know that President Roosevelt he was awful fine,

He helped the crippled boys and he almost healed the blind,

Oh yes, gonna miss President Roosevelt.

Well he’s gone, he’s gone, but his spirit always live on.

He traveled out East, he traveled to the West,

But of all the Presidents, President Roosevelt was the best,

Oh yes, gonna miss [etc.]

Well now he traveled by land and he traveled by sea,

He helped the United States boys, and he also helped Chinese,

Oh yes, gonna miss [etc.]

President Roosevelt went to Georgia boy, and he ride around and round, (twice)

I guess he imagined he seen that Pale Horse when they was trailin’ him down.

Oh yes, gonna miss [etc.]

Well now the rooster told the hen “I want to crow,

You know President Roosevelt has gone, can’t live in this shack no more,” Oh yes, we’re gonna miss President Roosevelt,

Well he’s gone, he’s gone, but his spirit always’ll live on.

Source: Paul Oliver, Blues Fell This Morning, Meaning in the Blues. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990, 261–262.

Document 5.11.3

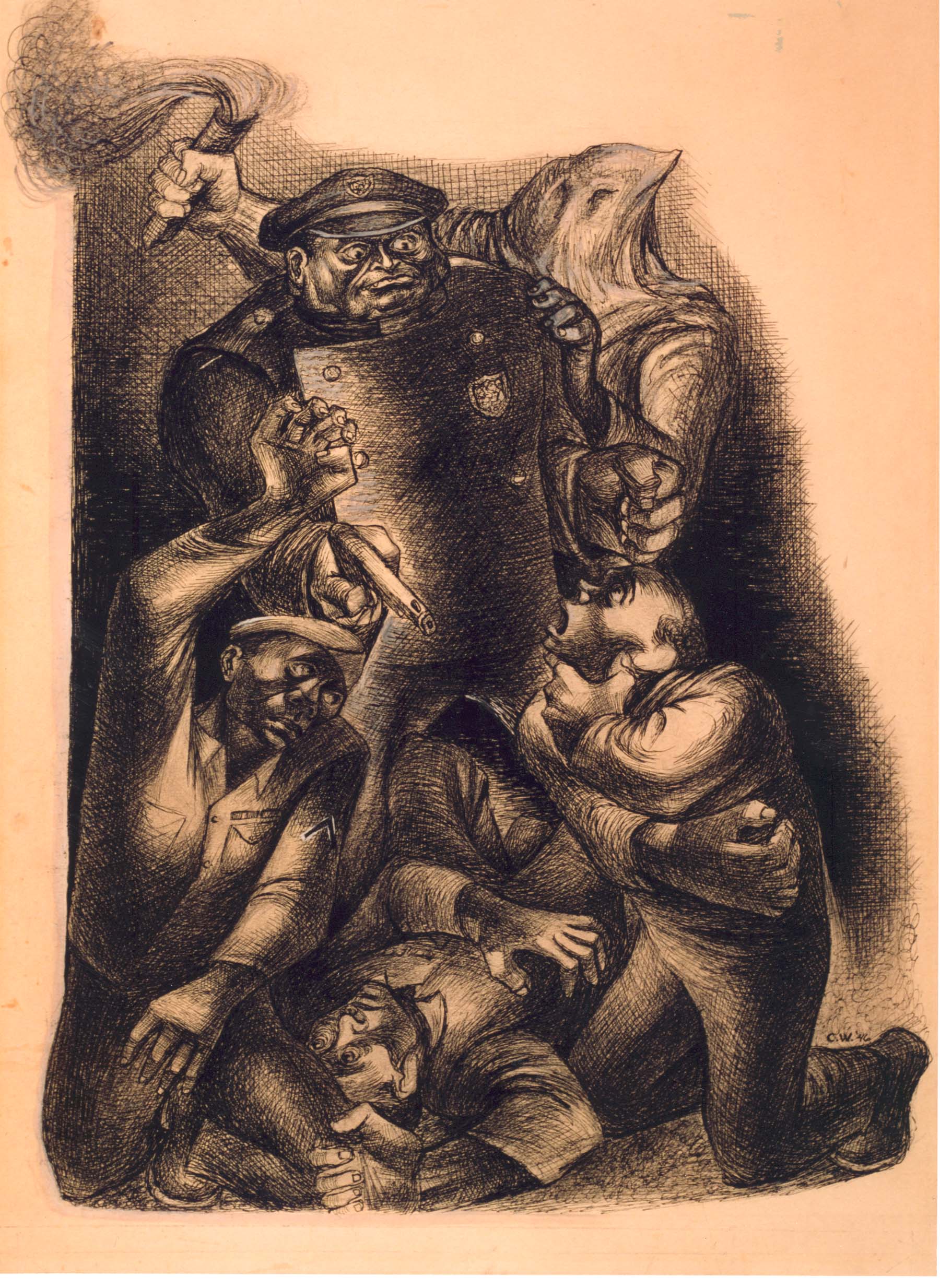

In order to prepare for the Gallery Walk, place the following photos on posters around the room depicting segregation and inequality as well as progress and Black achievement during the 1940s.

Have students do a gallery walk as a class. Instruct students to walk around the room in three rounds, answering each round’s question directly on each poster.

Assign 3-4 students to each poster, and have them read through all the comments on their assigned poster and report out to the class. They should share the main idea of the document and at least one student comment that resonated with the group.

Have students write a paragraph in response to the following question:

Have students read the unedited interview with former slave Mose Davis written down by Ed Whitley from the Federal Writers Project and analyze it using the OPCVL Document Analysis Protocol

Lead a class discussion about students’ main takeaways from the document analysis.

Edwin Driskell’s interview of former slave Mose Davis

Between 1936 and 1938, writers and journalists working under the Works Progress Administration (WPA) interviewed more than 2,300 former slaves from across the South. Most of the men and women interviewed were born into slavery in the last years preceding the Civil War, and their first-hand accounts create a permanent record of their experiences on plantations, in cities, and on small farms. Keep in mind that almost all interviews were conducted by white individuals; that situation may have altered to varying degrees the details black people shared. Nevertheless, taken together, the slave narratives offer a view of slavery in North America unlike any other.

In one of Atlanta’s many alleys lives Mose Davis, an ex-slave who was born on a very large plantation 12 miles from Perry, Georgia. His master was Colonel Davis, a very rich old man, who owned a large number of slaves in addition to his vast property holdings. Mose Davis says that all the buildings on this plantation were whitewashed, the lime having been secured from a corner of the plantation known as the “the lime sink.” Colonel Davis had a large family and so he had to have a large house to accommodate these members. The mansion, as it was called, was a great big three-storied affair surrounded by a thick growth of cedar trees.

Mose’s parents, Jennie and January Davis, had always been the property of the Davis family, naturally he and his two brothers and two sisters never knew any other master than “The Old Colonel.” Mr. Davis says that the first thing he remembers of his parents is being whipped by his mother who had tied him to the bed to prevent his running away. His first recollection of his father is seeing him take a drink of whiskey from a five gallon jug. When asked if this wasn’t against the plantation rules “Uncle Mose” replied: “The Colonel was one of the biggest devils you ever seen—he’s the one that started my daddy to drinking. Sometimes he used to come to our house to git a drink hisself.”

Mose’s father was the family coachman. “All that he had to do was to drive the master and his family and to take care of the two big grey horses that he drove. Compared to my mother and the other slaves he had an easy time,” said Uncle Mose, shaking his head and smiling: “My daddy was so crazy about the white folks and the horses he drove until I believe he thought more of them than he did of me. One day while I was in the stable with him one of the horses tried to kick me and when I started to hit him Daddy cussed me and threatened to beat me.”

His mother, brothers, and sisters, were all field hands, but there was never any work required of Mose, who was play-mate and companion to Manning, the youngest of Colonel Davis’ five sons. These two spent most of the time fishing and hunting. Manning had a pony and buggy and whenever he went to town he always took Mose along.

Field hands were roused, every morning by the overseer who rang the large bell near the slave quarters. Women and young children were permitted to remain at home until 9 o’clock to prepare breakfast. At 9 o’clock these women had to start to the fields where they worked along with the others until sundown. The one break in the day’s work was the noon dinner hour. Field hands planted and tended cotton, corn, and the other produce grown on the plantation until harvest time when everybody picked cotton. Slaves usually worked harder during the picking season than at any other time. After harvest, the only remaining work was cleaning out fence corners, splitting rails building fences and numerous other minor tasks. In hot weather, the only work was shelling corn. There was no Sunday work other than caring for the stock.

On this plantation there were quite a few skilled slaves mostly blacksmiths, carpenters, masons, plasterers, and a cobbler. One of Mose’s brothers was a carpenter.

All slaves too old for field work remained at home where some took care of the young children, while others worked in the loom houses helping make the cloth and the clothing used on the plantation. Since no work was required at night, this time was utilized by doing personal work such as the washing and the repairing of clothing, etc.

On the Fourth of July or at Christmas Colonel Davis always had a festival for all his slaves. Barbecue was served and there was much singing and dancing. These frolics were made merrier by the presence of guests from other plantations. Music was furnished by some of the slaves who also furnished music at the mansion whenever the Col. or some of the members of his family had a party. There was also a celebration after the crops had been gathered.

Although there was only one distribution of clothing per year nobody suffered from the lack of clothes because this one lot had enough to last a year if properly cared for. The children wore one piece garments, a cross between a dress and a slightly lengthened shirt, made of homespun or crocus material. No shoes were given them until winter and then they got the cast-offs of the grown ups. The men all wore pants made of material know as “susenberg.” The shirts and under wear were made of another cotton material. Dresses for the women were of striped homespun. All shoes were made on the premises of the heaviest leather, clumsely fashioned and Uncle Mose says that slaves like his father who worked in the mansion, were given much better clothing. His father received of “The Colonel” and his grown sons many discarded clothes. One of the greatest thrills of Mose’s boyhood was receiving first pair of “ausenberg” pants. As his mother had already taught him to knit (by using four needles at one time) all that he had to do was to go to his hiding place and get the socks that he had made.

None of the clothing worn by the slaves on this particular plantation was bought. Everything was made by the slaves, even to the dye that was used.

Asked if there was sufficient food for all slaves, Uncle Mose said “I never heard any complaints. At the end of each week every family was given some fat meat, black molasses, meal and flour in quantity varying with the size of the family. At certain intervals during the week, they were given vegetables. Here too, as in everything else, Mose’s father was more fortunate than the others, since he took all his meals at the mansion where he ate the same food served to the master and his family. The only difference between week-day and Sunday diet was that biscuits were served on Sundays. The children were given only one biscuit each. In addition to the other bread was considered a delicacy. All food stuff was grown on the plantation.

The slave quarters were located a short distance below the mansion. The cabins one-roomed weatherboard structures were arranged so as to form a semi-circle. There was a wide tree-lined road leading from the master’s home to these cabins.

Furnishings of each cabin consisted of one or two benches, a bed, and a few cooking untensils. These were very crude, especially the beds. Some of them had four posts while the ends of others were nailed to the walls. All lumber used in their construction was very heavy and rough. Bed springs were unheard of—wooden slats being used for this purpose. The mattresses were large ausenberg bags stuffed to capacity with hay, straw, or leaves. Uncle Mose told about one of the slaves, named Ike, whose entire family slept on bare pine straw. His children were among the fattest on the plantation and when Colonel Davis tried to make him put this straw in a bag he refused claiming that the pine needles kept his children healthy.

The floors and chimneys on the Davis Plantation were made of wood and brick instead of dirt and mud as was the case on many of the other surrounding plantations. One window (with shutters instead of window panes) served the purpose of ventilation and light. At night pine knots or candles gave light. The little cooking that the slaves did at home was all done at the open fireplace.

Source: From Born in Slavery: Slave Narratives from the Federal Writers’ Project, 1936-1938. Georgia Narrative, Volume IV, Part 1. http://memory.loc.gov

Document 5.11.11

Place students into pairs and assign each pair one of the Black leaders or Black-led organizations below.

Have students use the internet to research the following questions:

Each pair creates a campaign flier for their leader. Their goal is to highlight their leaders’ accomplishments and views. Have the students share their posters with the class and discuss the following questions together:

For this Socratic Seminar, have students read A. Philip Randolph’s speech, “A Call to the March” to discuss the Double Victory campaign.

After the seminar, lead a reflection in which students answer the following question:

Born in Crescent City, Florida, Asa Philip Randolph (1889–1979) graduated in 1907 from Cookman Institute in Jacksonville, the first high school for blacks in Florida. Four years later he moved to New York City and entered the vibrant milieu of Harlem. Influenced by W. E. B. Du Bois’ Souls of Black Folks, he began his lifelong pursuit of social and economic justice for African Americans. Randolph organized the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (see Lesson 12) and negotiated the first contract ever between a black union and a major American corporation. During and after World War II, Randolph was at the forefront of efforts to end racial discrimination in industry and the armed forces. In 1957, he became the first black to be elected vice president of the AFL-CIO. He spent his life fighting for the rights of black working men and women.

“Call to the March,” a speech by A. Philip Randolph, July 1, 1941

We call upon you to fight for jobs in National defense.

We call upon you to struggle for the integration of Negroes in the armed forces, such as the Air Corps, Navy, Army and Marine Corps of the Nation.

We call upon you to demonstrate for the abolition of Jim-Crowism in all Government departments and defense employment.

This is an hour of crisis. It is a crisis of democracy. It is a crisis of minority groups. It is a crisis of Negro Americans.

What is this crisis?

To American Negroes, it is the denial of jobs in Government defense projects. It is racial discrimination in Government departments. It is widespread Jim-Crowism in the armed forces of the Nation.

While billions of the taxpayers’ money are being spent for war weapons, Negro workers are being turned away from the gates of factories, mines and mills––being flatly told, “NOTHING DOING.” Some employees refuse to give Negroes jobs when they are without “union cards,” and some unions refuse Negro workers union cards when they are “without jobs.”

What shall we do?

What a dilemma!

What a runaround!

What a disgrace!

What a blow below the belt!

‘Though dark, doubtful and discouraging, all is not lost, all is not hopeless. ‘Though battered and bruised, we are not beaten, broken or bewildered.

Verily, the Negroes’ deepest disappointments and direst defeats, their tragic trials and outrageous oppressions in these dreadful days of destruction and disaster to democracy and freedom, and the rights of minority peoples, and the dignity and independence of the human spirit, is the Negroes’ greatest opportunity to rise to the highest heights of struggle for freedom and justice in Government, in industry, in labor unions, education, social service, religion and culture.

With faith and confidence of the Negro people in their own power for self-liberation, Negroes can break down the barriers of discrimination against employment in National Defense. Negroes can kill the deadly serpent of race hatred in the Army, Navy, Air and Marine Corps, and smash through and blast the Government, business and labor-union red tape to win the right to equal opportunity in vocational training and re-training in defense employment.

Most important and vital to all, Negroes, by the mobilization and coordination of their mass power, can cause PRESIDENT ROOSEVELT TO ISSUE AN EXECUTIVE ORDER ABOLISHING DISCRMINATIONS IN ALL GOVERNMENT DEPARTMENTS, ARMY, NAVY, AIR CORPS AND NATIONAL DEFENSE JOBS.

Of course, the task is not easy. In very truth, it is big, tremendous and difficult.

It will cost money.

It will require sacrifice.

It will tax the Negroes’ courage, determination and will to struggle. But we can, must and will triumph.

The Negroes’ stake in national defense is big. It consists of jobs, thousands of jobs. It may represent millions, yes, hundreds of millions of dollars in wages. It consists of new industrial opportunities and hope. This is worth fighting for.

But to win our stakes, it will require an “all-out,” bold and total effort and demonstration of colossal proportions.

Negroes can build a mammoth machine of mass action with a terrific and tremendous driving and striking power that can shatter and crush the evil fortress of race prejudice and hate, if they will only resolve to do so and never stop, until victory comes.

Dear fellow Negro Americans, be not dismayed in these terrible times. You possess power, great power. Our problem is to harness and hitch it up for action on the broadest, daring and most gigantic scale.

In this period of power politics, nothing counts but pressure, more pressure, and still more pressure, through the tactic and strategy of broad, organized, aggressive mass action behind the vital and important issues of the Negro. To this end, we propose that ten thousand Negroes MARCH ON WASHINGTON FOR JOBS IN NATIONAL DEFENSE AND EQUAL INTEGRATION IN THE FIGHTING FORCES OF THE UNITED STATES.

An “all-out” thundering march on Washington, ending in a monster and huge demonstration at Lincoln’s Monument will shake up white America.

It will shake up official Washington.

It will give encouragement to our white friends to fight all the harder by our side, with us, for our righteous cause.

It will gain respect for the Negro people.

It will create a new sense of self-respect among Negroes.

But what of national unity?

We believe in national unity which recognizes equal opportunity of black and white citizens to jobs in national defense and the armed forces, and in all other institutions and endeavors in America. We condemn all dictatorships, Fascist, Nazi and Communist. We are loyal, patriotic Americans, all.

But, if American democracy will not defend its defenders; if American democracy will not protect its protectors; if American democracy will not give jobs to its toilers because of race or color; if American democracy will not insure equality of opportunity, freedom and justice to its citizens, black and white, it is a hollow mockery and belies the principles for which it is supposed to stand.

To the hard, difficult and trying problem of securing equal participation in national defense, we summon all Negro Americans to march on Washington. We summon Negro Americans to form committees in various cities to recruit and register marchers and raise funds through the sale of buttons and other legitimate means for the expenses of marchers to Washington by buses, train, private automobiles, trucks, and on foot.

We summon Negro Americans to stage marches on their City Halls and Councils in their respective cities and urge them to memorialize the President to issue an executive order to abolish discrimination in the Government and national defense.

However, we sternly counsel against violence and ill-considered and intemperate action and the abuse of power. Mass power, like physical power, when misdirected is more harmful than helpful.

We summon you to mass action that is orderly and lawful, but aggressive and militant, for justice, equality and freedom.

Crispus Attucks marched and died as a martyr for American independence. Nat Turner, Denmark Vesey, Gabriel Prosser, Harriet Tubman and Frederick Douglass fought, bled and died for the emancipation of Negro slaves and the preservation of American democracy.

Abraham Lincoln, in times of the grave emergency of the Civil War, issued the Proclamation of Emancipation for the freedom of Negro slaves and the preservation of American democracy.

Today, we call upon President Roosevelt, a great humanitarian and idealist, to follow in the footsteps of his noble and illustrious predecessor and take the second decisive step in this world and national emergency and free American Negro citizens of the stigma, humiliation and insult of discrimination and Jim-Crowism in Government departments and national defense.

The Federal Government cannot with clear conscience call upon private industry and labor unions to abolish discrimination based upon race and color as long as it practices discrimination itself against Negro Americans.

Source: The Black Worker, May 1941Reprinted in Meier, August, ed. Black Protest Thought in the Twentieth Century. New York: Bobbs-Merrill Co., 1971.

Document 5.14.2

As a class, read the list of demands that the Black community presented to President Roosevelt. Then place students into groups of 3-4. In their groups, students read the executive orders. Have students work together to complete a comparison chart to highlight similarities between the executive orders and to contemplate differences.

Lead a class discussion to reflect on the following questions:

Demands handed to President Roosevelt by African American leaders on June 18, 1941

PROPOSALS OF THE NEGRO MARCH-ON-WASHINGTON COMMITTEE

TO

PRESIDENT ROOSEVELT

FOR

URGENT CONSIDERATION

POINT 1. An executive order forbidding the awarding of contracts to any concern, Navy

Yard or Army Arsenal which refuses employment to qualified persons on

account of race, creed or color. In the event that such discrimination

continues to exist, the Government shall take over the plant for continuous

operation, by virtue of the authority vested in the President of the United

States, as Commander-in-Chief of the armed forces and as expressed in the

Proclamation declaring a state of unlimited national emergency, May 27, 1941.

POINT 2. An executive order abolishing discrimination and segregation on account of

race, creed or color in all departments of the Federal Government.

POINT 3. An executive order abolishing discrimination in vocational and defense training

courses for workers in National Defense whether financed in whole or in part by

the Federal Government.

POINT 4. An executive order abolishing discrimination in the Army, Navy, Marine, Air

Corps and all other branches of the armed services.

POINT 5. That the President ask the Congress to pass a law forbidding the benefits of the

National Labor Relations Act to Labor Unions denying Negroes membership

through Constitutional provisions, ritualistic practices or otherwise.

POINT 6. That the President issue instructions to the United States Employment Services

that available workers be supplied in order of their registration without regard to

race, creed or color.

Source: “March on Washington Movement: Principles and Structures” folder, A. Phillip Randolph Papers, Library of Congress

Document 5.14.4

Executive Order 9346, establishing a new Committee on Fair Employment Practice, issued by President Roosevelt, May 27, 1943

May 27, 1943

In order to establish a new Committee on Fair Employment Practice, to promote the fullest utilization of all available manpower, and to eliminate discriminatory employment practices, Executive Order No. 8802 of June 25, 1941, as amended by Executive Order No. 8823 of July 18, 1941, is hereby further amended to read as follows:

Whereas the successful prosecution of the war demands the maximum employment of all available workers regardless of race, creed, color, or national origin; and

Whereas it is the policy of the United States to encourage full participation in the war effort by all persons in the United States regardless of race, creed, color, or national origin, in the firm belief that the democratic way of life within the Nation can be defended successfully only with the help and support of all groups within its borders; and

Whereas there is evidence that available and needed workers have been barred from employment in industries engaged in war production solely by reason of their race, creed, color, or national origin, to the detriment of the prosecution of the war, the workers' morale, and national unity:

Now, Therefore, by virtue of the authority vested in me by the Constitution and statutes, and as President of the United States and Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy, I do hereby reaffirm the policy of the United States that there shall be no discrimination in the employment of any person in war industries or in Government by reason of race, creed, color, or national origin, and I do hereby declare that it is the duty of all employers, including the several Federal departments and agencies, and all labor organizations, in furtherance of this policy and of this Order, to eliminate discrimination in regard to hire, tenure, terms or conditions of employment, or union member-ship because of race, creed, color, or national origin.

It is hereby ordered as follows:

l. All contracting agencies of the Government of the United States shall include in all contracts hereafter negotiated or renegotiated by them a provision obligating the contractor not to discriminate against any employee or applicant for employment because of race, creed, color, or national origin and requiring him to include a similar provision in all subcontracts.

2. All departments and agencies of the Government of the United States concerned with vocational and training programs for war production shall take all measures appropriate to assure that such programs are administered without discrimination because of race, creed, color, or national origin.

3. There is hereby established in the Office for Emergency Management of the Executive Office of the President a Committee on Fair Employment Practice, hereinafter referred to as the Committee, which shall consist of a Chairman and not more than six other members to be appointed by the President. The Chairman shall receive such salary as shall be fixed by the President not exceeding $10,000 per year. The other members of the Committee shall receive necessary traveling expenses and, unless their compensation is otherwise prescribed by the President, a per diem allowance not exceeding $25 per day and subsistence expenses on such days as they are actually engaged in the performance of duties pursuant to this Order.

4. The committee shall formulate policies to achieve the purposes of this Order and shall make recommendations to the various Federal departments and agencies and to the President which it deems necessary and proper to make effective the provisions of this Order. The Committee shall also recommend to the Chairman of the War Manpower Commission appropriate measures for bringing about the full utilization and training of manpower in and for war production without discrimination because of race, creed, color, or national origin.

5. The Committee shall receive and investigate complaints of discrimination forbidden by this Order. It may conduct hearings, make findings of fact, and take appropriate steps to obtain elimination of such discrimination.

6. Upon the appointment of the Committee and the designation of its Chairman, the Fair Employment Practice Committee established by Executive Order No. 8802 of June 25, 1941, hereinafter referred to as the old Committee, shall cease to exist. All records and property of the old Committee and such unexpended balances of allocations or other funds available for its use as the Director of the Bureau of the Budget shall determine shall be transferred to the Committee. The Committee shall assume jurisdiction over all complaints and matters pending before the old Committee and shall conduct such investigations and hearings as may be necessary in the performance of its duties under this Order.

7. Within the limits of the funds which may be made available for that purpose, the Chairman shall appoint and fix the compensation of such personnel and make provision for such supplies, facilities, and services as may be necessary to carry out this Order. The Committee may utilize the services and facilities of other Federal departments and agencies and such voluntary and uncompensated services as may from time to time be needed. The Committee may accept the services of State and local authorities and officials, and may perform the functions and duties and exercise the powers conferred upon it by this Order through such officials and agencies and in such manner as it may determine.

8. The Committee shall have the power to promulgate such rules and regulations as may be appropriate or necessary to carry out the provisions of this Order.

9. The provisions of any other pertinent Executive Order inconsistent with this Order are hereby superseded.

Document 5.14.10

Executive Order 9981, desegregating the armed forces, issued by President Truman, July 26, 1948

In December 1946, President Harry Truman created the President’s Committee on Civil Rights to investigate violations and recommend improvements. The committee issued a report To Secure These Rights. It highlighted the lack of progress and recommended specific Congressional actions. However, Congress failed to respond. President Truman bypassed the legislative body. Executive Order 9981 was one of two executive orders he issued July 26, 1948. The other one put in place fair employment practices in civilian agencies of the federal government.

Establishing the President's Committee on Equality of Treatment and Opportunity In the Armed Forces.

WHEREAS it is essential that there be maintained in the armed services of the United States the highest standards of democracy, with equality of treatment and opportunity for all those who serve in our country's defense:

NOW THEREFORE, by virtue of the authority vested in me as President of the United States, by the Constitution and the statutes of the United States, and as Commander in Chief of the armed services, it is hereby ordered as follows:

1. It is hereby declared to be the policy of the President that there shall be equality of treatment and opportunity for all persons in the armed services without regard to race, color, religion or national origin. This policy shall be put into effect as rapidly as possible, having due regard to the time required to effectuate any necessary changes without impairing efficiency or morale.

2. There shall be created in the National Military Establishment an advisory committee to be known as the President's Committee on Equality of Treatment and Opportunity in the Armed Services, which shall be composed of seven members to be designated by the President.

3. The Committee is authorized on behalf of the President to examine the rules, procedures and practices of the Armed Services in order to determine in what respect such rules, procedures and practices may be altered or improved with a view to carrying out the policy of this order. The Committee shall confer and advise the Secretary of Defense, the Secretary of the Army, the Secretary of the Navy, and the Secretary of the Air Force, and shall make such recommendations to the President and to said Secretaries as in the judgment of the Committee will effectuate the policy hereof.

4. All executive departments and agencies of the Federal Government are authorized and directed to cooperate with the Committee in its work, and to furnish the Committee such information or the services of such persons as the Committee may require in the performance of its duties.

5. When requested by the Committee to do so, persons in the armed services or in any of the executive departments and agencies of the Federal Governemt shall testify before the Committee and shall make available for use of the Committee such documents and other information as the Committee may require.

6. The Committee shall continue to exist until such time as the President shall terminate its existence by Executive order.

Harry Truman The White House

July 26, 1948

Document 5.14.13

Divide students into different interest groups and ask them to develop a policy proposal to respond to the demands of the Black community during the Double Victory campaign. Assign representatives for the following interest groups:

Students should spend the first 45 minutes researching their group’s position on structural racism and the Double Victory campaign. Proposals should contain the following elements:

In the second half of the activity, place students around a conference table and instruct them to negotiate a plan that works for all stakeholders. They should come up with a written policy to which all interest groups agree.

Demands handed to President Roosevelt by African American leaders on June 18, 1941

PROPOSALS OF THE

NEGRO MARCH-ON-WASHINGTON COMMITTEE

TO

PRESIDENT ROOSEVELT

FOR

URGENT CONSIDERATION

POINT 1. An executive order forbidding the awarding of contracts to any concern, Navy

Yard or Army Arsenal which refuses employment to qualified persons on

account of race, creed or color. In the event that such discrimination

continues to exist, the Government shall take over the plant for continuous

operation, by virtue of the authority vested in the President of the United

States, as Commander-in-Chief of the armed forces and as expressed in the

Proclamation declaring a state of unlimited national emergency, May 27, 1941.

POINT 2. An executive order abolishing discrimination and segregation on account of

race, creed or color in all departments of the Federal Government.

POINT 3. An executive order abolishing discrimination in vocational and defense training

courses for workers in National Defense whether financed in whole or in part by

the Federal Government.

POINT 4. An executive order abolishing discrimination in the Army, Navy, Marine, Air

Corps and all other branches of the armed services.

POINT 5. That the President ask the Congress to pass a law forbidding the benefits of the

National Labor Relations Act to Labor Unions denying Negroes membership

through Constitutional provisions, ritualistic practices or otherwise.

POINT 6. That the President issue instructions to the United States Employment Services

that available workers be supplied in order of their registration without regard to

race, creed or color.

Source: “March on Washington Movement: Principles and Structures” folder, A. Phillip Randolph Papers, Library of Congress

Document 5.14.4

Divide students into four small groups and assign each group one of the following source documents, all of which demonstrate the contributions, experiences, and roles of Black Americans to the WWII effort.

Each group should answer the following questions and then share out with the class:

Transcript of recording “Dear Mr. President,” from African American woman in Texas, January or February 1942

Unidentified Woman: Mr. Roosevelt, you can't realize how I'm enjoying having this opportunity to talk to you. The man who's recording this record here says that you're going to hear this and he said I could talk about anything else I wanted to talk about. I know and you know and I guess everybody else knows the thing that you're thinking about most now is this war. Believe me I suppose I'm thinking about it so much is because I got a brother who's in the army. I'm living with my mother, she's a widow. That's the only brother I have and when he left here he was mighty glad to get in the army. I don't know if he's so glad to be there now though from all the letters I've been getting from him. And my brother, I don't mean that he's against our country or anything like that, but he's not so satisfied with the treatment that he's getting up there. He thinks it could be just a little better. I know that he thinks that you and Mrs. Roosevelt have the interest of all the people in this country at heart. That you think everybody should be treated fairly and equally, but I just don't see and he doesn't see either why some of those ideas that you stand so staunchly for might be carried out down here. He says that they've got a lot of dirty work to do in camp, not that they mind working, but nobody else has to do it but just the Negro soldiers. They don't give them guns because they're afraid that they might start a race riot. And I know my brother wouldn't threaten that kind of thing because he's always been law-abiding and a good citizen. He really is. I live right here in the east part of town and we never have had any trouble out there and I know that my brother could respect the carrying of arms just like any other man whether he be white, black, or blue.

I'm just wondering Mr. Roosevelt if you couldn't see to it that something could be done about helping my boys. I see my boys because I think of all my colored brothers as a brother here. It's up to us and this might give me an opportunity to talk to you to see if you won't help us out a little bit. I know you must get ???[audio unclear] up here every day at this kind, but I want you to know that this is coming from the heart and I really mean it. And that something ought to be done about it, because I'd hate to have our people keep on thinking that they don't have an active part in this war because [sound fades] their soldiers are getting treated so badly in some of the camps.

They don't have any entertainment for soldiers ???[audio unclear], whereas the white soldiers have lounges, and guest houses, and everything that they could wish for as far as facilities with ???[audio unclear]. Why our boys don't have anything, but a post exchange and that's not very good for entertaining when that's all you have to do. I think they could stand that, if they were just treated a little better when it comes to other things that are most important like duties, and promotions, and ???[audio unclear] the [election (?)] and the army when it gets you put you off, somewhere off by yourself, the Army Air Corps says "No." I had a friend the other day went down here to the recruiting station. You know when they read you the regulations for Army Air Corps pilots saying that they needed so many of the boys to come over and register. And he's twenty-three and he went down there and he said the man told him they just don't have any need for them. Didn't give him any reason what so ever, they just didn't want him. And that's the way it's been over in San Antonio and here too. It's just the same way, they just don't want him in the Army Air Corps.

We had two other fellows, one's eighteen, one's nineteen, Bob Long and his brother, they went down there and they didn't even get in let alone get in the air corps. They didn't even get an ???[audio unclear] [laughs]. Well I think that's pretty bad when a situation gets like that and I feel like if they want to help this country. So they really want to belong as a real citizen, not as a part citizen.

Those fellas are good boys, just as good as they'll do fine anywhere. They don't want to see a Japanese side German victory. We want to make things good over here just as it is. We want to see if we can't have equal rights. I think we want a good ???[audio unclear] to begin with before the war comes home, but now that the war is on I hope that something will turn better for us, and I hope you'll do all you can. I know you're going to do all you can to help us make them better. Because we need it. You need it. I need it.

I think I can say that we need it just a little better ???[audio unclear] than you can because I'm on the other side of the fence. I see, and I read about my fellow Negroes being lynched and abused. And I just don't see, it seems like all the hope is something else to be fighting for. Democracy, and equal rights, justice, and freedom for all. And down here it's not that at all. And I think that America is the best place in the world to live, and can be made a better place. We don't want to go to Germany, and we have no idea of going back to Africa, we want to be good American citizens. We want to stay over here and work, live, live peacefully and lawfully. And I think we just ought to have that chance and I know you think so too because I've seen write ups in the papers about what you and Mrs. Roosevelt thought about everything. I read about the incident about Marion Anderson about two or three years ago. I understand Mrs. Roosevelt ??? [audio unclear]. You don't understand how much those kinds of things make us feel that we still have a chance. Especially people in your position when they do the right thing.

Source: Library of Congress

Document 5.14.6

The Presidential Unit Citation for Extraordinary Heroism to the 761st Tank Battalion, United States Army, 197x, January 24, 1978

By virtue of the authority vested in me as President of the United Armed Forces of the United States, I have today awarded

THE PRESIDENTIAL UNIT CITATION (ARMY)

TO THE

761st TANK BATTALION, UNITED STATES ARMY

The 761st Tank Battalion distinguished itself by extraordinary gallantry, courage, professionalism and high esprit de corps displayed in the accomplishment of unusually difficult and hazardous operations in the European Theater of Operations from 31 October 1944 to 6 May 1945. During 183 days in combat, elements of the 761st - the first United States Army tank battalion committed to battle comprised of black soldiers - were responsible for inflicting thousands of enemy casualties and for capturing, destroying, or aiding in the liberation of more than 30 major towns, 4 airfields, 3 ammunition supply dumps, 461 wheeled vehicles, 34 tanks, 113 large guns, 1 radio station, and numerous individual and crew- served weapons. This was accomplished while enduring an overall casualty rate approaching 50 percent, the loss of 71 tanks, and in spite of extremely adverse weather conditions, very difficult terrain not suited to armor operations, heavily fortified enemy positions and units, and extreme shortages of replacement personnel and equipment. The accomplishments are outstanding examples of the indomitable spirit and heroism displayed by the tank crews of the 761st. In one of the first major combat actions of the 761st, in the vicinity of Vic-sur-Seille and Morville-les- Vic, France, the battalion faced a reinforced enemy division. Despite the overwhelming superiority of enemy forces, elements of the battalion initiated a furious and persistent atttack which caused defending enemy elements to withdraw. While pursuing the enemy, tanks of the 761st were immobilized before an anti-tank ditch. Savage fire from enemy bazooka and rocket launcher teams, positioned 50 yards beyond the ditch, disabled many of the vehicles. Crewmen dismounted the disabled tanks, resulted in the elimination of many of the positions and virtually destroyed two enemy companies while permitting the escape of other tanks and crews and eventual completion of the mission. From 5 January 1945 to 9 January 1945, the 761st engaged the 15th Panzer Division in the vicinity of Tillet, Belgium. Suffering severe casualties and damage to their tanks, the 761st attacked and counter-attacked throughout the five-day period against a numerically superior force in both personnel and equipment , and on 9 January 1945 the men of the 761st routed the enemy from Tillet and captured the town. This action was significant in that the enemy was prevented from further supply of its forces encircling Bastogne, and the United States troops there, because of the closing of the Brussels-Bastogne highway by the men of the 761st. One of the most significant accomplishments of the 761st began 20 March 1945 when, acting as the armor spearhead, the unit broke through the Seigfried Line into the Rhine plain, allowing units of the 4th Armored Division to move through to the Rhine River. During the period 20 March 1945 to 23 March 1945 the battalion, after operating far in advance of friendly artillery, encountered the fiercest of enemy resistance in the most heavily defended area of the war theater. Throughout the 72-hour period of the attack, elements of the 761st assaulted and destroyed enemy fortifications with a speed and intensity that enabled the capture or destruction of 7 Siegfried towns, 31 pill-boxes, 49 machine gun emplacements, 61 anti-tank guns, 451 vehicles, 11 ammunition trucks, 4 self-propelled guns, one 170mm artillery piece, 200 horses, and one ammunition dump. Enemy casualties totaled over 4,100 and of those captured it was determined that the 761st in its Siegfried Line attack had faced elements of 14 different German divisions. The accomplishments of the 761st in the Siegfried area were truly magnificent as the successful crossing of the Rhine River into Germany was totally dependent upon the accomplishment of their mission. The men of the 761st Tank Battalion, while serving as a separate battalion with the 26th, 71st, 79th, 87th, 95th and 103d Infantry Divisions, the 17th Airborne Division, and 3d, 7th, and 9th Armies in 183 continuous days in battle, fought major engagements in six European countries, participated in four major allied campaigns, and on 6 May 1945, as the easternmost American soldiers in Austria, ended their combat missions by joining with the First Ukrainian Army (Russian) at the Enn River, Steyr, Austria. Throughout this period of combat, the courageous and professional actions of the members of the "Black Panther" battalion, coupled with their indomitable fighting spirit and devotion to duty, reflect great credit on the 761st Tank Battalion, the United States Army, and this Nation.

Source: U.S. Army Center of Military History

http://www.army.mil/cmh-pg/topics/afam/DAGO5-78.htm

Document 5.14.9

In 1948 the United States Congress considered the enactment of the first peacetime draft law in the nation’s history. High-ranking government officials and leading generals favored the preservation of segregated armed forces. In testimony before the Senate Armed Services Committee, A. Philip Randolph, President of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, who had become national treasurer of the Committee Against Jimcrow in Military Service and Training, solemnly warned the congressmen that if a draft law were passed without requiring desegregation, he would lead Negroes in a massive civil disobedience campaign and urge them to register and be conscripted in a jim crow army.

Randolph was the most influential black leader taking this position, and his stand was certainly one of the considerations that persuaded President Harry S. Truman to issue a directive ending segregation in the armed forces. Thus was settled an issue about which Negroes had agitated constantly since Randolph listed it among the original demands of the proposed March on Washington of 1941.

Excerpts from testimony before the Senate Armed Services Committee by A. Philip Randolph, March 31, 1948

Mr. Chairman:

Mr. Grant Reynolds, national chairman of the Committee Against Jimcrow in Military Service and Training, has prepared for you in his testimony today a summary of wartime injustices to Negro soldiers––injustices by the military authorities and injustices by bigoted segments of the police and civilian population. The fund of material on this issue is endless, and yet, three years after the end of the war, as another crisis approaches, large numbers of white Americans are blissfully unaware of the extent of physical and psychological aggression against and oppression of the Negro soldier.

Without taking time for a thorough probe into these relevant data––a probe which could enlighten the nation––Congress may now heed Mr. Truman’s call for Universal Military Training and Selective Service, and in the weeks ahead enact a jimcrow conscription law and appropriate billions for the greatest segregation system of all time. In a campaign year, when both major parties are playing cynical politics with the issue of civil rights, Negroes are about to lose the fight against jimcrowism on a national level. Our hard-won local gains in education, fair employment, hospitalization, housing are in danger of being nullified––being swept aside, Mr. Chairman, after decades of work––by a federally enforced pattern of segregation…

There can be no doubt of my facts. Quite bluntly, Chairman Walter G. Andrews of the House Armed Services Committee told a delegation from this organization that the War Department plans segregated white and Negro battalions if Congress passes a draft law…

We have released all of this damaging information to the daily press, to leaders of both parties in Congress, and to supposedly liberal organizations. But with a relative handful of exceptions, we have found our white “friends” silent, indifferent, even hostile…

This situation––this conspiracy of silence, shall I say?––has naturally commanded wide publicity in the Negro press. I submit for the record a composite of newspaper clippings. In my travels around the country I have sounded out Negro public opinion and confirmed for myself the popular resentment as reflected by the Negro press. I can assure members of the Senate that Negroes do put civil rights above the high cost of living and above every other major issue of the day, as recently reported by the Fortune Opinion Poll, I believe. Even more significant is the bitter, angry mood of the Negro in his present determination to win those civil rights in a country that subjects him daily to so many insults and indignities.

With this background, gentlemen, I reported last week to President Truman that Negroes are in no mood to shoulder a gun for democracy abroad so long as they are denied democracy here at home. In particular, they resent the idea of fighting or being drafted into another jimcrow Army. I passed this information on to Mr. Truman not as threat, but rather as a frank, factual survey of Negro opinion.

Today I should like to make clear to the Senate Armed Services Committee and through you, to Congress and the American people that passage now of a jimcrow draft may only result in a mass civil disobedience movement along the lines of the magnificent struggles of the people of India against British imperialism. I must emphasize that the current agitation for civil rights is no longer a mere expression of hope on the part of Negroes. On the one hand, it is a positive, resolute outreaching for full manhood. On the other hand, it is an equally determined will to stop acquiescing in anything less. Negroes demand full, unqualified first-class citizenship.

In resorting to the principles of direct-action techniques of Gandhi, whose death was publicly mourned by many members of Congress and President Truman, Negroes will be serving a higher law than any passed by a national legislature in an era when racism spells our doom. They will be serving a law higher than any decree of the Supreme Court which in the famous Winfred Lynn case evaded ruling on the flagrantly illegal segregation practiced under the wartime Selective Service Act. In refusing to accept compulsory military segregation, Negro youth will be serving their fellow men throughout the world.

I feel qualified to make this claim because of a recent survey of American psychologists, sociologists and anthropologists. The survey revealed an overwhelming belief among these experts that enforced segregation on racial or religious lines has serious and detrimental psychological effects both on the segregated groups and on those enforcing segregation. Experts from the South, I should like to point out, gentlemen, were as positive as those from other sections of the country as to the harmful effects of segregation. The view of these social scientists were based on scientific research and on their own professional experience.

So long as the Armed Services propose to enforce such universally harmful segregation not only here at home but also overseas, Negro youth have a moral obligation not to lend themselves as world-wide carriers of an evil and hellish doctrine. Secretary of the Army Kenneth C. Royall clearly indicated in the New Jersey National Guard situation that the Armed Services do have every intention of prolonging their anthropologically hoary and untenable policies.

For 25 years now the myth has been carefully cultivated that Soviet Russia has ended all discrimination and intolerance, while here at home the American Communists have skillfully posed as champions of minority groups. To the rank-and-file Negro in World War II, Hitler’s racism posed a sufficient threat for him to submit to the jimcrow Army abuses. But this factor of minority group persecution in Russia is not present, as a popular issue, in the power struggle between Stalin and the United States. I can only repeat that this time Negroes will not take a jimcrow draft lying down. The conscience of the world will be shaken as by nothing else when thousands and thousands of us second-class Americans choose imprisonment in preference to permanent military slavery.

While I cannot with absolute certainty claim results at this hour, I personally will advise Negroes to refuse to fight as slaves for a democracy they cannot possess and cannot enjoy. Let me add that I am speaking only for myself not even for the Committee Against Jimcrow in Military Service and Training, since I am not sure that all its members would follow my position. But Negro leaders in close touch with GI grievances would feel derelict in their duty if they did not support such a justified civil disobedience movement––especially those of us whose age would protect us from being drafted. Any other course would be a betrayal of those who place their trust in us. I personally pledge myself to openly counsel, aid and abet youth, both white and Negro, to quarantine any jimcrow conscription system, whether it bear the label of UMT or Selective Service…

From coast to coast in my travels I shall call upon all Negro veterans to join this civil disobedience movement and to recruit their younger brothers in an organized refusal to register and be drafted. Many veterans, bitter over Army jimcrow, have indicated that they will act spontaneously in this fashion, regardless of any organized movement. “Never again,” they say with finality.

I shall appeal to the thousands of white youth in schools and colleges who are today vigorously shedding the prejudices of their parents and professors. I shall urge them to demonstrate their solidarity with Negro youth by ignoring the entire registration and induction machinery. And finally I shall appeal to Negro parents to lend their moral support to their sons––to stand behind them as they march with heads high to federal prisons as a telling demonstration to the world that Negroes have reached the limit of human endurance––that is, in the words of the spiritual, we’ll be buried in our graves before we will be slaves.

May I, in conclusion, Mr. Chairman, point out that political maneuvers have made this drastic program our last resort. Your party, the party of Lincoln, solemnly pledged in its 1944 platform a full-fledged Congressional investigation of injustices to Negro soldiers. Instead of that long overdue probe, the Senate Armed Services Committee in this very day is finally hearing testimony from two or three Negro veterans for a period of 20 minutes each. The House Armed Services Committee and Chairman Andrews went one step further and arrogantly refused to hear any at all! Since we cannot obtain an adequate Congressional forum for our grievances, we have no other recourse but to tell our story to the peoples of the world by organized direct action. I don’t believe that even a wartime censorship wall could be high enough to conceal news of a civil disobedience program. If we cannot win your support for your own Party commitments, if we cannot ring a bell in you by appealing to human decency, we shall command your respect and the respect of the world by our united refusal to cooperate with tyrannical injustice.

Since the military, with their Southern biases, intend to take over America and institute total encampment of the populace along jimcrow lines, Negroes will resist with the power of non-violence, with the weapons of moral principles, with the good-will weapons of the spirit, yes with the weapons that brought freedom to India. I feel morally obligated to disturb and keep disturbed the conscience of jimcrow America. In resisting the insult of jimcrowism to the soul of black America, we are helping to save the soul of America. And let me add that I am opposed to Russian totalitarian communism and all its works. I consider it a menace to freedom. I stand by democracy as expressing the Judean-Christian ethic. But democracy and Christianity must be boldly and courageously applied for all men regardless of race, color, creed or country.

We shall wage a relentless warfare against jimcrow without hate or revenge for the moral and spiritual progress and safety of our country, world peace and freedom.

Finally let me say that Negroes are just sick and tired of being pushed around and we just don’t propose to take it, and we do not care what happens.

Document 5.14.12

Have students research interest convergence theory (developed by Derrick Bell) and come up with a class definition. Begin with the identified sources and use the internet for additional resources if needed. (Teachers should note that the internet contains some highly politicized and incorrect sources on interest convergence theory. This activity presents an opportunity to work with your school librarian to help guide students in evaluating their sources.)

Students should individually write a paragraph reflection in response to the following question:

Have students share their responses in small groups and discuss the following as a whole group:

Each student selects two leaders from their study of the New Deal and the Double Victory campaign. The two leaders should have different perspectives. Students should research their two leaders and create an evidence-based script for a podcast interview including the two historical figures and themselves (the student) as the interviewer. The interview should cover at least two topics from the unit of study and showcase historically-accurate different perspectives on the topics. Students can cast their peers to play the roles and record the podcast, or they can submit the written script, depending on teacher preference.

Please login or sign up to access the student view functions.