Unit

Years: 1865 – 1877

Economy & Society

Prior to this unit, students should be familiar with the history of enslavement in the United States and the ideology of White supremacy that was used to justify enslaving Black people. Students should also have some knowledge of the Civil War period and its immediate aftermath, including the causes, aims, and results of the war, the Emancipation Proclamation, and the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments. Students should also be able to enter into discussions with an understanding of basic economic terms and concepts, including labor, capital, production, contract, agriculture, and industry.

You may want to consider after teaching this lesson: A. Philip Randolph & the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters

The history of African American labor during Reconstruction, 1863-1877, reflects the struggle between freedpeople seeking economic independence and former enslavers seeking to retain their hold on power. Confronted with a myriad of obstacles, African Americans fought to gain and maintain economic freedom through strategies ranging from collective bargaining to emigrating from the South.

In the era following the Civil War, African Americans recognized that achieving economic independence was essential to truly become equal participants in society. However, former enslavers recognizing their reliance on servitude and African American labor, worked to create new structures to maintain the economic dependence of African American people. The history of African American labor during this time period, 1863-1877, known as Reconstruction, reflects the struggle of these conflicting tensions.

Black Codes:

Following the Civil War, Southern States established laws referred to as Black Codes. These laws, in place between 1865-1866, restricted the rights and freedoms of African American people. (These laws became illegal after the 14th Amendment was passed, but Southern states found ways to bypass the protections through Jim Crow laws passed after the end of Reconstruction).

After the Civil War, although freedpeople aspired to own their own land, most of the land remained in the hands of White people.Black Codes restricted opportunities for African Americans to gain access to land. As a result, the majority of freedpeople ended up as tenant farmers or sharecroppers, working for White landowners. Although sharecropping initially seemed like progress for African American farmers as they could benefit from their own labor, the social and political climate soon turned it into an oppressive system that resembled slavery. In many cases, it resulted in freedpeople once again working on plantations for little pay.

In addition to farming, African Americans worked in various professions and trades. However, they faced challenges in achieving equal opportunities for this work as well. In the rapidly industrializing North, there was growing tension between workers and employers. Labor unions were becoming more numerous and powerful, as workers sought better conditions and wages. Yet, African American workers often found themselves isolated from collective efforts for change.

Blatant attempts to undermine the abolition of slavery and hamper economic independence outraged African Americans and their allies, including a political group known as the Radical Republicans. The Radical Republicans were a group of politicians within the Republican party known for their opposition to slavery and efforts to secure civil rights for African Americans during Reconstruction. Their efforts and the efforts from others within the Federal government and from the North led to three acts: the creation of the Freedmen’s Bureau (1865), the Civil Rights Act (1866), and the Fourteenth Amendment (ratified in 1868). These acts extended federal oversight in the South and allowed African Americans more opportunity to explore some of the promises of freedom. Although the passage of the three acts represented progress,for African Americans, obstacles to economic independence continued to be enormous.

40 Acres and a Mule:

After the war, as before, African American labor provided the lifeblood for southern agriculture, which was the backbone of the southern economy. Freedpeople’s hopes for ownership of land had been raised by General Sherman’s Field Order Number Fifteen (January 16, 1865), which gave almost half a million acres of land to freedpeople, and by the Freedmen’s Bureau’s promise of “40 acres and a mule.” Throughout the South, African Americans worked on land confiscated from former plantations, assuming that after several years of farming they would have the funds needed to buy the land outright as implied by the aforementioned promises. Sharing this vision, Thaddeus Stevens, leader of the Radical Republicans in the House of Representatives, introduced a bill for widespread confiscation of former Confederate land to be redistributed to freedpeople.

Yet even Stevens’ Radical Republican allies balked at the precedent that would be set by such an act. On July 9, 1867, the New York Times claimed “(Land confiscation) is a question not of humanity, not of loyalty, but of fundamental relation of industry to capital; and sooner or later, if begun at the South, it will find its way into the cities of the North”. Thaddeus Stevens’ bill eventually foundered in the House.

President Johnson’s efforts to pardon former rebels in 1865-66, coupled with a general reluctance to dramatically interfere with the rights of property owners and an ongoing undercurrent of racism and terror that even the government’s best efforts were powerless to quell, dashed most freedpeople’s chances of landholding. Most ended up in some form of tenant farming, or sharecropping. As a result, while sharecropping initially constituted a step forward for African American farmers by allowing them to benefit from their own labor, the social and political climate soon reduced it to an economically oppressive structure little better than slavery.

Labor Unions:

Throughout the United States, African Americans worked in all professions and trades, not just in agriculture. African Americans struggled for equality of opportunity. In the industrializing North, the 1860s and 70s were already a time of growing tension between labor and bosses. Labor unions were growing in numbers, power and militancy. Through them, workers sought better conditions and wages. The question was, where did African American workers, whose numbers had swelled with the abolition of slavery, fit in? Were they to be welcomed into the fight as fellow workers, or shunned as inferiors and potential scabs? Like their White counterparts, African American workers used strikes to protest unfair conditions. However, it quickly became clear that the vast majority of White workers wanted nothing to do with their African American counterparts. African Americans were actively excluded from unions; in response, they formed their own labor organizations. The first convention of the Colored National Labor Union (CNLU) in Washington, D.C., was held on December 6, 1869 and led by Isaac Myers. Phillip Foner writes in The Black Worker that the convention “demonstrated that, by 1869, northern and southern black leaders had reached the conclusion that blacks could achieve equal employment opportunities and better pay only through independent organization.” (10)

The CNLU met for the last time in 1871. Conditions for African American workers had deteriorated with the demise of the Radical Republicans and the rise of terror tactics in the South. Some workers continued to work for equality through Black unions; others opted to leave the South altogether. A minority managed to find economic success in the South despite all the obstacles they faced, while the vast majority struggled to support themselves and their families. Although voices for equality and justice never ceased, the late 1870s marks the beginning of a nadir in African American labor history.

Teaching Activity: Reconstructing the South: A Role Play, Zinn Education Project

Videos & Lesson Plans: The Reconstruction Era and the Fragility of Democracy, Facing History and Ourselves

Videos & Lesson Plans: Reconstruction: America After the Civil War. PBS.

Article: African Americans and the American Labor Movement. Prologue Magazine, National Archives, 1997.

Book: Foner, Eric. Freedom’s Lawmakers: A Directory of Black Officeholders during Reconstruction. New York: Oxford University Press, 1993.

Book: Foner, Eric. Reconstruction (Updated Edition): America’s Unfinished Revolution 1863–1877. New York: Harper Collins, 2014.

Book: Foner, Philip Sheldon. Organized Labor and the Black Worker, 1619-1973. New York: Praeger, 1974.

Book: Trotter, William Joe Jr. Workers on Arrival: Black Labor in the Making of America. California: University of California Press, 2019.

Several of the sources in this lesson contain language or images that may be disturbing to students, including racist language and ideas and depictions of racialized violence. It is imperative that these be shared with students with great care, as they can trigger painful emotions in students, such as anger, sadness, fear, and shame. As sources are reviewed and discussions unfold, students may feel that their identity is under attack if the lesson and activities are not structured with care. Moreover, if not examined critically, sources that contain racist content can perpetuate racist ideas. Use the guidelines below when sharing content with students.

Connecting the study of history to the present increases its relevance and emotional salience for students, but it also prepares students to apply the lessons of history as informed citizens. As students learn about African American struggles for economic opportunities and independence during Reconstruction, support them in making connections to current events, such as unionization efforts and migration patterns, as well as to local and family history. For instance, students might interview family members who have been involved with unions or research unions that are active in their community.

The history of African American labor during Reconstruction, the time period following the end of the Civil War, reflects the conflict between two contrary efforts.

African Americans, no longer enslaved, identified opportunities and made efforts towards gaining economic independence. While former enslavers, recognizing their reliance on servitude and African American labor, worked to create new structures to maintain the economic dependence of African American people.

After the Civil War, Southern States established laws referred to as Black Codes. These laws, in place between 1865-1866, restricted the rights and freedoms of African American people. One of the biggest impacts was around land ownership. Although freedpeople aspired to own their own land, most of the land remained in the hands of White people, and the Black Codes restricted African American efforts to gain access to land. As a result, the majority of freedpeople became tenant farmers or sharecroppers, working for White landowners. Although sharecropping initially seemed like progress for African American farmers as they could benefit from their own labor, the social and political climate soon turned it into an oppressive system that resembled slavery. In many cases, it resulted in freedpeople once again working on plantations for little pay.

In addition to farming, African Americans worked in various professions and trades. However, they faced challenges in achieving equal opportunities in these areas as well. In the rapidly industrializing North, there was growing tension between workers and employers. Labor unions were becoming more numerous and powerful as workers sought better conditions and wages. Yet, African American workers often found themselves isolated from collective efforts for change.

Northern politicians within the federal government sought to support African Americans in addressing these inequities by ending the Black Codes and subverting similar efforts through new legislation and the creation of a new agency, The Freedmen’s Bureau. The Freedmen’s Bureau was created to assist African Americans transition from enslavement to freedom. This included supporting education through the establishment of schools, finding land and homes, and rejoining families that had been separated by enslavers.

The Bureau also worked to mediate fair contracts for wages across industries but frequently in agriculture.

The combined efforts of African American people, abolitionists, and the Bureau eventually led to the passing of the Civil Rights Act in 1866 and the ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment. The Fourteenth Amendment, passed in 1868, granted the rights of citizens to all people born in the United States, regardless of race. There seemed to finally be positive progress and movement in the structures impacting the lives of African American people. Then, in 1872, The Freedmen’s Bureau was dismantled, leading to both detrimental changes in conditions and the beginning of what came to be known as terror tactics.

Select the activities and sources you would like to include in the student view and click “Launch Student View.”

It is highly recommended that you review the Teaching Tips and sources before selecting the activities to best meet the needs and readiness of your students. Activities may utilize resources or primary sources that contain historical expressions of racism, outdated language or racial slurs.

Activate students’ background knowledge and interest by asking them the following questions:

Have students read the Contract for Agricultural Laborers, Alabama, 1874. Depending on the reading levels in your class, you may have students read alone, in pairs, or together as a group. While reading, students should consider the guiding question: Is this a good contract for laborers? They can use an Advantages & Disadvantages graphic organizer to keep track of information.

Bring the class back together to discuss:

Below is a typical contract for wage work, which was less popular than sharecropping. Most African Americans preferred working for a portion of the harvest during this time period.

_________________________________________________________________________

He will be required to be ready for work by sunrise in mornings, then repair to same and render good and faithful service until noon, when he will be allowed for dinner one hour, during winter and spring and one hour and a half during the summer months. Then to perform faithful labor until sundown. Then feed stock or perform any other necessary duty demanded of him by his employer or agent.

All time lost to be deducted from the wages of the laborer, to be assessed by his employer.

Bad or unfaithful labor, careless breakage or loss of tools, willful destruction of property or abuse of stock will be charged for, and deducted out of the wages of the laborer.

The laborer binds himself to be obedient to his employer or agent. To obey all orders willingly and cheerfully of either employer or agent, and to render good and faithful service at all times.

It shall be the duty of the laborer to attend faithfully to the stock of his employee on the Sabbath.

The employer binds himself to furnish three pounds and a half of sound Bacon and twelve pounds of good meal per week, and quarters free of rent.

It is understood that the laborer is to receive one half of his wages per month, at the expiration of each month, and the remainder at the expiration of the contract in case he shall leave before expiration of his term of service without consent of his employer, he thereby forfeits all claim upon the employer for the unpaid part of his wages. It is, however, understood that the employer has the right to discharge the laborer at any time by a liquidation of all dues.

Source: Henry B. Cobb, "The Negro as a Free Laborer in Alabama, 1865-1875,"Midwest Journal, 6 (Fall1954): 43-4. reprinted in Foner, Philip S., and Roanld L. Lewis, eds. Black Worker: A Documentary History, Volume II: The Black Worker During the Era of the National Labor Union. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1978.

Document 4.10.1: Contract for Agricultural Laborers, Alabama, 1874.

In this activity, students engage with primary source materials that describe and illustrate the terror tactics used by the Ku Klux Klan and other White supremacist groups to oppress the freedpeople. These materials are likely to be disturbing or distressing to many students, and need to be handled with sensitivity. See the “Teacher Tips” section above for guidelines on addressing disturbing content.

Before sharing the primary sources with students, explain that you will be sharing sources that depict and/or describe the terror tactics that were targeted at African Americans during Reconstruction. Give students the option of disengaging with the materials, if necessary. Throughout the activity, check in with students about their emotional reactions.

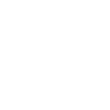

Students should examine the “I Am Committee” broadside and the “Excerpts from Testimony taken by the Joint Select Committee to Inquire into the Condition of Affairs in the Late Insurrectionary States.” (Note: Before reading this document, it would be helpful to review the definition of Radical Republican with students and share with them that in this source, “radical” refers to Radical Republicans.)

Bring the class together to discuss the following questions:

(Optional) Invite students to respond to the terror tactics described in the “I am Committee” broadside and/or the Ku Klux Klan investigation in writing or art. Students may choose to “talk back” to the perpetrators through drawing, writing a poem, journaling, preparing a short speech, etc.

The extent of the violence by secret societies against freedpeople was so extensive that Congress

established a special committee to investigate. In the nine South Carolina counties examined by

the committee, members of the Ku Klux Klan had lynched and murdered 35 men, whipped 262 men

and women, and shot, maimed, or burned the property of 101 African Americans.

_____________________________________________________________________________________

Charlotte Fowler (colored) sworn and examined:

[Mrs. Fowler first describes how a masked man shot her husband in the head in the doorway of his

home in the middle of the night.]

[Questions asked by committee member] Mr. STEVENSON:

Q. What are these men called that go about masked in that way?

A. I don't know; they call them Ku-Klux.

Q. How long have they been going about in that neighborhood?

A. I don't know how long; they have been going a long time, but they never pestered the plantation

until that night. I have heard of Ku-Klux, but they never pestered Mr. Jones before.

Q. Did your old man belong to any party?

A. Yes sir.

Q. What party?

A. The radical.

Q. How long had he belonged to them?

A. Ever since they started the voting.

Q. Was he a pretty strong radical?

A. Yes sir; a pretty strong radical.

Q. Did he work for that party?

A. Yes sir.

Q. What did he do?

A. He held up for it, and said he never would turn against the United

States for anybody, as the democrats wanted him to.

Q. Did he talk to the other colored people about it?

A. No, sir; he never said nothing much. He was a man that never said much but just what he was

going to do. He never traveled anywhere to visit people only when they had a meeting; then he

would go there to the radical meeting, but would come back home again.

Q. Did he make speeches at those meetings?

A. No, sir.

Q. Did they make him president of their meetings?

A. I don't know about that.

Q. Did you ever go with him?

A. No, sir.

Q. Did they ever make him president or vice-president, or put him upon the platform?

A. No, sir. Several, I heard, went there and did, but he never undertook such a thing. He would go

to hear what the best of them had to say, but he never did anything.

[Question asked] by the CHAIRMAN:

Q. Are the colored people afraid of these people that go masked?

A. Yes, sir; they are as 'fraid as death of them. There is now a whole procession of people that have

left their houses and are lying out. You see the old man was so old, and he did no harm to anybody;

he didn't believe anybody would trouble him.

[Questions asked] by Mr. STEVENSON:

Q. Did he vote at the last election?

A. Yes, sir.

GEORGE W. GARNER sworn and examined.

[Questions asked] by the CHAIRMAN:

Q. Do you live in this county?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. What part of it?

A. I live east of this place—about seven miles from here.

Q. In what township?

A. Pacolet Township.

Q. What business do you follow?

A. Farming.

Q. How long have you lived in this county?

A. I have been living in this county since January last a year ago.

Q. Where did you come from?

A. From Union County, in this State.

Q. Are you a native of this State?

A. Yes, sir. I was born and raised in Union County.

Q. Have you suffered any violence at the hands of any person in this county?

A. From persons in this county or some others, I have.

Q. Go on and tell in what manner it was inflicted upon you, and when it was.

A. I had two attacks; the first was on the 4th of March last, on

Saturday night; the second was on that night two weeks, which would make it the 18th of March.

Q. Go on and tell what occurred each time.

A. On the 4th of March there came a body of men to my house. They were all around my house

before I knew they were there, and were hallooing and beating and thumping the house. I was

nearly asleep, and as quick as I awoke I jumped up. They told me to open the door. I told them I

would do so. They told me to strike a light before I opened the door. I lighted a lamp and set it on a

desk by the side of the house. I opened the door. These men were standing in front of the door with

pistols drawn. They were knocking at the other door also. I said, "Gentlemen, somebody is

knocking at the other door; let me open it." They let me turn around and open it. There were five

men there. While I was opening that door more men came through the other door and into the room

where I was. To the best of my mind, there were twelve men in all in my house. My wife thinks

there were more, but I did not see them. They asked me to take a walk. I told them I would. I asked

them to let me put on my clothes and shoes. They told me to put on my shoes, but not my clothes.

They took me out and tied my hands together and hit me a few strokes and sent me back to the

house.

Q. What was said?

A. They told me I must be a good citizen to the county. I asked them if I had not been. They said

they reckoned as good as any. I told them if I lacked anything, it was from not knowing what a

citizen should be. I thought I had done my duty. They said I should quit my damned radical way of

doing, and should no longer vote a republican ticket, and if I did they would come back and kill me.

Source: Reprinted in Foner, Philip S., and Ronald L. Lewis, eds. Black Worker: A Documentary

History, Volume II: The Black Worker During the Era of the National Labor Union. Philadelphia:

Temple University Press, 1978.

Document 4.10.3: Excerpts from Testimony taken by the Joint Select Committee to Inquire into the

Condition of Affairs in the Late Insurrectionary States, Spartanburgh, South Carolina, July 6 and 7,

1871

Have students read Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amendment. Make sure that students understand that this amendment extended the rights of citizens to African Americans. Ask students, what rights does this amendment explicitly grant to citizens? What other rights did U.S. citizens have at this time period? Refer students to the Bill of Rights, as needed.

As a class, or working with partners, create a list of the rights guaranteed to citizens by the Constitution.

Discuss:

Students should base their claims on particular passages from the Fourteenth Amendment or the Bill of Rights.

AMENDMENT XIV

Section 1.

All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside. No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

Section 2.

Representatives shall be apportioned among the several States according to their respective numbers, counting the whole number of persons in each State, excluding Indians not taxed. But when the right to vote at any election for the choice of electors for President and Vice-President of the United States, Representatives in Congress, the Executive and Judicial officers of a State, or the members of the Legislature thereof, is denied to any of the male inhabitants of such State, being twenty-one years of age, and citizens of the United States, or in any way abridged, except for participation in rebellion, or other crime, the basis of representation therein shall be reduced in the proportion which the number of such male citizens shall bear to the whole number of male citizens twenty-one years of age in such State.

Section 3.

No person shall be a Senator or Representative in Congress, or elector of President and Vice-President, or hold any office, civil or military, under the United States, or under any State, who, having previously taken an oath, as a member of Congress, or as an officer of the United States, or as a member of any State legislature, or as an executive or judicial officer of any State, to support the Constitution of the United States, shall have engaged in insurrection or rebellion against the same, or given aid or comfort to the enemies thereof. But Congress may by a vote of two-thirds of each House, remove such disability.

Section 4.

The validity of the public debt of the United States, authorized by law, including debts incurred for payment of pensions and bounties for services in suppressing insurrection or rebellion, shall not be questioned. But neither the United States nor any State shall assume or pay any debt or obligation incurred in aid of insurrection or rebellion against the United States, or any claim for the loss or emancipation of any slave; but all such debts, obligations and claims shall be held illegal and void.

Section 5.

The Congress shall have power to enforce, by appropriate legislation, the provisions of this article.

Students will explore a collection of documents that demonstrate some of the collective strategies that African American laborers used to seek economic opportunity. They will extract information from the documents in order to answer these three guiding questions:

There are six documents included in this collection. Many of them are short, but they are of varying reading levels. Teachers have several options for using them, depending on class reading levels and time constraints. Students might read all the documents with a partner over the course of a class, to finish for homework, compiling individual lists in response to the three guiding questions. Students could then compare their lists in a large group the next day. Students could also be divided into “expert groups” with each group being responsible for understanding one document. Each expert group would then report out to the class and together the class could compile the lists. Finally, the teacher could choose several of the documents and go over them as a class, making the lists together. Whatever the format, it is important to emphasize that students must point to the exact words or phrases in the documents that gave them the information.

After looking at the lists, students should discuss or respond in writing to the following questions:

Black men generally went on strike for the same reasons their White counterparts did—for better pay and improved working conditions. Most strikes were peaceful, but not all.

_____________________________________________________________________________________

CHARLESTON, W. Va., April 17.—An extensive and important strike among the laborers upon the new Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad, from White Sulphur Springs to Kanawha Falls, is in progress. The strike is for about four month's back pay, and the number of men engaged in it is estimated at from 800 to 1,000, mostly negroes.

The strike began near Stretcher's Neck, on New River, and the negroes from there marched along the road westwardly, compelling all laborers, of both colors, with whom they came in contact to stop work.

The strikers were augmented in strength as they proceeded, and when they arrived at Kanawha Falls last night there was a very large force of them. They have continually shown a very hostile and mutinous feeling towards the railroad company and its officers. At the Hawk's Nest, about twelve miles east of Kanawha Falls, on New River, the negroes took possession of the station, and among other acts of violence broke and turned a switch so that a train going east a short time afterwards collided with a construction train upon the switch. The collision resulted in the wrecking of an engine and slight injury of several persons on board the train. At about the same time a very large rock and two or three stumps were rolled down the steep mountain next above the Hawk's Nest upon the track, and the probabilities are undoubted that the strikers were the perpetrators of the acts.

The belligerent spirit manifested by the negroes has inspired travellers and residents of the sections in which they are figuring with fear and anxiety, and the conduct of the strikers thus far means mischief beyond a question.

The amount for which the strike was made is variously estimated, but it is probably in the neighborhood of $150,000. Much apprehension is felt by the people along the line, as the negroes will undoubtedly do a great deal of sacking and plundering for the means of subsistence, the country in that section being comparatively poor in supplies. Major A. H. Perry and Colonel Vancleve, Superintendents of the road, have gone to the New River country to see what can be done in the matter, but the strikers are bitterly determined to have their money or hold the road and stop the telegraph and trains.

If an adjustment is not effected in the course of forty-eight hours, or even less, the trains will probably stop running from necessity, as landslides are constantly occurring on the road.

E. C. B.

Source: Reprinted in Foner, Philip S., and Ronald L. Lewis, eds. Black Worker: A Documentary History, Volume II: The Black Worker During the Era of the National Labor Union. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1978.

Document 4.10.4: “Colored Trouble at Stretcher’s Neck,” New York World, April 20, 1873

In Florida, Black workers struck for higher wages and shorter workdays. Unlike the strike in West Virginia, there were no physical conflicts.

______________________________________________________________________________________

The mill owners having refused to allow the reduction of a day's work to ten hours, in compliance with the demand of the Labor League, the colored laborers, with preconcerted action, refused to go to work yesterday morning before 7 o'clock—The owners of the mills, determined not to yield, told them that they must continue to work as heretofore, or find other employment. Both parties stood firm.

Messrs. Alsop & Clerk went to work at the usual time, with a few colored men in their employ. Messrs. Eppinger, Russell & Co., C. A. Fairchild, A. Wallace and others were occupied as usual the first day of every month, in cleaning boilers and making general repairs. They fired up last night, and will go to work this morning with such help as they have been able to secure. The mill men do not anticipate any serious interference with their business by the strike.

The Superintendents of the mills claim that the strikers have not heretofore averaged ten hours labor a day, notwithstanding they are required, at this session of the year, to go to work at 6 A.M., and continue, except for dinner, until near sunset; that they do not average more than 8 or 8 1/2 hours in the winter, and from 11 to 12 in the summer. Besides they have a relief of from one to two hours while changing saws, etc., almost daily. During the day the strikers endeavored to induce the few men who continued work at Clark's mill to desist, and threatened violence in case they refused. Mr. Clark sent word to the Mayor requesting the protection of the police for his employees, which was promptly granted. Up to the time of going to press no serious disturbance has occurred. A resort to violence is discountenanced by the leaders of the movement.—

Source: Reprinted in Foner, Philip S., and Ronald L. Lewis, eds. Black Worker: A Documentary History, Volume II: The Black Worker During the Era of the National Labor Union. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1978.

Document 4.10.5: “Strike at Saw Mills,” Jacksonville Republican, Florida, June 3, 1873.

Note: a beat refers to a specific geographical area or community within a larger county. This term is often used in the Southern United States to describe small administrative or electoral subdivisions similar to a district or precinct. In this document, Mt. Meigs Beat is a local area where both Black and white planters live and work, organizing meetings to discuss agricultural and labor issues affecting their community.

______________________________________________________________________________________

There was a meeting held at Pike Road Station in this county, composed almost exclusively of negroes, on Saturday last, at which the following resolutions were adopted:

WHEREAS, The crops of the present year have not yielded a sufficient supply to satisfy the demands of the planters and laborers of Mt. Meigs Beat; and

Whereas, The white planters of said beat have held several meetings, for the purpose of devising plans whereby they may better their conditions, without allowing the colored planters and laborers an equal voice, wherein their interests are concerned as well; and

Whereas, We, the laborers, hold that we are in no way responsible for the failure of the crops, and that we have worked as faithful during the present year as we have any year since emancipation, but in consequence of a bad season, wet weather and rain, followed up by the ravages of cotton worms, &c., came the present calamity.—Therefore be it

Resolved, That we consider it nothing but humane and just that the white planters should take our poverty and distresses under advisement, as well as their own, we being the bone and sinew of the beat, and in times past while seasons were favorable rendered them valuable service at their own prices. Be it further resolved, That we desire to cultivate a friendly relation with the white planters of this beat, but cannot do so, if they insist upon discriminating against us by framing to deprive us of our rightful privilege to have a voice in settling the price of our labor, and the hours in which we shall work.

Be it further resolved, That we believe, and do acknowledge, that a thorough and economical cultivation of the lands of this beat are essential to the peace and prosperity of both white and colored people, and that the most successful way to do that is for each to regard the other's interest as being as sacred as his own.

Be it further resolved, That we are willing to try another crop in the coming year, upon reasonable terms, provided we are allowed to have an equal voice in the settling of those terms and a reliable showing for the procurement of whatever we contract for.

Be it further resolved, That we ask a careful consideration of these resolutions by the white planters of this beat, and a timely response, so that we may know upon what to depend for the coming year.

Source: Reprinted in Foner, Philip S., and Ronald L. Lewis, eds. Black Worker: A Documentary History, Volume II: The Black Worker During the Era of the National Labor Union. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1978.

Document 4.10.6: “What Does it Mean?,” Advertiser and Mail, Montgomery, Alabama, November 4, 1873.

During the late summer of 1876, Black rice harvesters went on strike along South Carolina’s Combahee River.

_____________________________________________________________________________________

Editor, Standard & Commercial,

Beaufort, S.C., Aug. 24th, 1876.

Having been telegraphed by the Governor and Attorney-General to visit the disturbed district on the Combahee, I abandoned my trip to Midway, at which point I was to spend to-day, and with Lt. Gov. Cleaves we left the cars at Sheldon and upon out arrival at Gardners Corners, we found assembled at Mr. Pullet’s store, between forty and sixty white men mounted and armed with sixteen shooters, Spencer rifles, and double-barreled shotguns, and about one hundred and fifty colored men with sticks and clubs. Upon inquiry, I found that about three hundred strikers were collected on the road to Combahee.

I proceeded at once to this point and there found a large body of colored men and women. I called upon them for the cease of the strike and was informed by them that they refused to work for checks payable in 1880, and that they demanded money for their labor, and that if the planters would pay them in money they would go to work at the usual prices.

I did not find a single colored striker with any kind of deadly weapon about him, and found that they were peaceably inclined with no other object in view than to be paid in good money for honest labor; this they are determined to have or not to work.

The rice planters have been in the habit of using checks instead of money, which are not good at any but the Planters stores for the reason that they are payable in 1878 and 1880, and that when these checks are used in purchasing goods at these stores they become checks as change instead of money thus making it impossible for the laborers to purchase medicines, or employ physicians or obtain any thing except through the agency of the planter.

So far as violence on the part of the strikers is concerned there were warrants issued by Trial Justice Puller, for whipping one of their own number who had gone to work contrary to the agreement they had made in their own clubs, not to work for checks. These men upon being requested to give themselves up, walked out of the crowd and came into Beaufort without the Sheriff or even a guard, and were waiting in town hours before the arrival of the Sheriff.

The men were first taken to Trial Justice Puller, but he not being there, the men arrested came into Beaufort at the request of the Sheriff. At three o'clock the entire crowd had peaceably dispersed and no sign of a strike was visible.

It is due to Sheriff Sams to say that he informed the white men that he did not need their services, and it is due to them to say that they offered no violence to the strikers, during the time that I was present.

The following is the cause of the strike. [a sample of a check follows]

"50. Due--Fifty Cents, 60.

To Jonathan Lucas or Bearer, for labor under special contract. Payable on the first January,

1880. J. B. Bissell

The checks are issued in denominations of 5; 10; 25; and 50 cents.

Very Respectfully

ROBERT SMALL

Source: Reprinted in Foner, Philip S., and Ronald L. Lewis, eds. Black Worker: A Documentary History, Volume II: The Black Worker During the Era of the National Labor Union. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1978.

Document 4.10.7: “Robert Small on the Combahee Strike”, Savannah Tribune, Georgia, September 2, 1876

The petition was the first known collective action by Black women.

______________________________________________________________________________________

Jackson, Mississippi, June 20, 1866

Mayor Barrows—Dear Sir: —At a meeting of the colored Washerwomen of this city, on the evening of the 18th of June, the subject of raising the wages was considered, and owing to many circumstances, the following preamble and resolution were unanimously adopted:

Whereas, under the influence of the present high prices of all the necessaries of life, and the attendant high rates of rent, while our wages remain very much reduced, we, the washerwomen of the city of Jackson, State of Mississippi, thinking it impossible to live uprightly and honestly in laboring for the present daily and monthly recompense, and hoping to meet with the support of all good citizens, join in adopting unanimously the following resolution:

Be it resolved by the washerwomen of this city and county, That on and after the foregoing date, we join in charging a uniform rate for our labor, that rate being an advance over the original price by the month or day the statement of said price to be made public by printing the same, and anyone belonging to the class of washerwomen, violating this, shall be liable to a fine regulated by the class.

We do not wish in the least to charge exorbitant prices, but desire to be able to live comfortably if possible from the fruits of our labor. We present the matter to your Honor, and hope you will not reject it as the condition of prices call on us to raise our wages. The prices charged are:

$1.50 per day for washing

$15.00 per month for family washing

$10.00 per month for single individuals

We ask you to consider the matter in our behalf, and should you deem it just and right, your sanction of the movement will be gratefully received.

Yours, very truly,

The Washerwomen of Jackson.

Source: Reprinted in Foner, Philip S., and Ronald L. Lewis, eds. Black Worker: A Documentary History, Volume II: The Black Worker During the Era of the National Labor Union. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1978.

Document 4.10.8

Note: In this document, the N-word has been replaced with "n- - - - - " to avoid putting the racial slur into print.

_______________________________________________________________________________________

AFTERNOON SESSION

The National Union was called to order by the president, Mr. M. Moore, and the roll was called. A majority of the delegates answered to their names and the usual routine of business was pursued, until the reports of committees were called for. None being ready to report, the union went into a session for the "general good of the order."

The subject of the admission of negroes to the rights and privileges of the union was introduced, and provoked a lively discussion, in which many members engaged.

Among others, Mr. A. Martin, of No.2, Kentucky, gave a history of affairs in his vicinity. He said that in Lexington, Cynthiana, and Paris, the negroes were standing up for regular prices, and he was in favor of organizing colored unions.

Josiah Bradley, of No. 1, Kentucky, followed, and said that his union would never admit a n - - - - r into their fellowship. As an instance showing the feeling of bricklayers toward colored men, he told a story in regard to the erection of the Galt house in Louisville. A large number of men were engaged on the job, and one negro was put to work, but, as soon as he put in an appearance, all hands quit, and would not go to work until the negro was discharged.

Thos. Newton, of No.6, New York, obtained the floor and made a long speech against receiving negroes into the union, either local or national. "Although, I am willing to admit that we have got to consider this subject of colored bricklayers, yet still I am not willing to have them on an equality with me, and I know the Union I represent will endorse my position. The idea has been broached that we organize them into unions by themselves, but that will not do gentleman; they are a sensitive race, as sensitive as we are, and will not accept any such proposition. Either they will demand an equality on this floor, a right to hold office, and all the privileges of the order, or they will have nothing to do with us. I, for one, am not ready to grant them these privileges, and consider that the time has not yet arrived when negroes are better than white men.

T. C. Tinker, No. 1, Wisconsin, said, "although he represented a state so far north as Mason and Dixon's line, yet, still once in a while we see the color of the negro's face; indeed one of our unions has a member who has some negro blood in his veins, and yet can handle a trowel as well as any other bricklayer I ever saw, and is the corresponding secretary of the union. I want to ask for information whether if we give him a travelling card, it would be regarded by other local unions? For my part, I believe in elevating the negro, not for his sake, but for our own, as if he goes forth and cannot get into a local union, he will go to work for anyone, and at any price."

Josiah Bradley, No. 1, Kentucky, in reply, remarked, "that he would never recognize the travelling card borne by a negro, and if the national union saw fit to be displeased thereat, union No. 1 of Kentucky, would withdraw."

T. C. Tinker replied that he was no ultra-republican, but that he could not refrain from asking, "Is it not an accomplished fact that the negro has become a voter by the law of the land? Are we not butting our head against a fact?”

W. S. King, of No. 1, Maryland, arose very much excited, and had the constitution of his local union in his hand, from which he read a clause which inflicted a penalty of fifty dollar on any member who worked with a negro. That put aside all chance for discussion on his part, and he would only say, "the fifteenth amendment made a n - - - - - a white man, and in Baltimore we had to allow him to vote because we could not get around it, but we don’t allow him in our union. I wouldn't let a n - - - - - into our union, and if he came in I would get out. We will not recognize a n - - - - - bricklayer in Baltimore.” . . .

Source: Reprinted in Foner, Philip S., and Ronald L. Lewis, eds. Black Worker: A Documentary History, Volume II: The Black Worker During the Era of the National Labor Union. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1978.

Document 4.10.9: Convention of the Bricklayers National Union, January 9, 1871

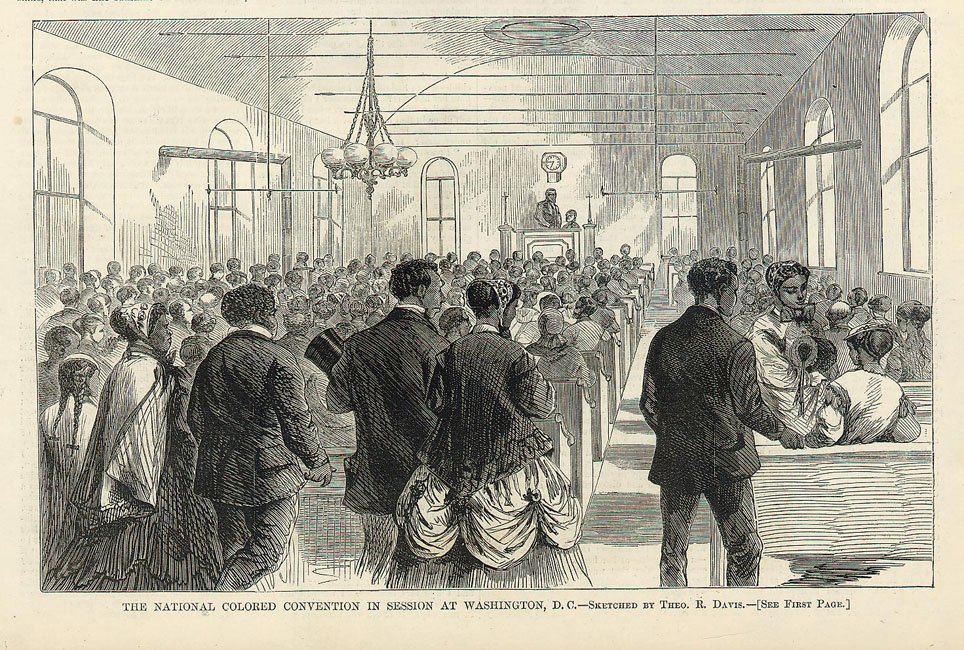

Working as a class or in small groups or partners, have students carefully examine the illustration of the National Colored Convention. Students can use an adaptation of the See, Think, Wonder thinking routine developed by Project Zero, a research center at the Harvard Graduate School of Education. Students can utilize the provided graphic organizer to organize their observations and to generate inferences and questions.

Share some background information with students about the origins of the Colored National Labor Union. In 1869, several Black delegates were invited to attend a meeting of the National Labor Union (NLU), which had been formed by White workers. Although the president of the NLU William Sylvis made a speech arguing for color-blindness, the White unions refused to allow African American members to join their ranks. In response to this, African American laborers organized their own organization, also called the National Labor Union, but more commonly referred to as the Colored National Labor Union (CNLU). In December 1869, 214 delegates attended the first Colored National Labor Union convention in Washington, D.C.

Next, have students read excerpts from the address of George T. Downing in the Proceedings of the Colored National Labor Convention. (Note: This document is 45 pages long. If you choose to use it, identify specific sections or passages you want students to look at before beginning the lesson.) Depending on the reading levels in your class, you may have students read alone, in pairs, or together as a group.

After reading, discuss:

In this activity, students will be exposed to some of the far-reaching options African Americans pursued in the face of the dimming economic reality in the years following the Civil War. After analyzing three options, students engage in a discussion about the benefits and drawbacks of a particular choice given the context and constraints and consider other possible options not covered in the documents but one that they think could have been viable in history.

First, have students read the three documents: 1) A Call for the Colored National Labor Union Convention; 2) Excerpts from “Resolution Adopted by Negro Convention Montgomery, Alabama; and 3) 150,000 Exiles Enrolled for Liberia. For each document, students should determine, “What does the author think African Americans should do in order to secure economic opportunity? And then consider, “What are the benefits and drawbacks of this option?”

Once students have engaged with the three sources, organize a discussion in which they will consider different perspectives on how African Americans could take action to secure their economic future.

*Before beginning the discussion with students, ensure you have established classroom expectations for behavior grounded in respect and empathy for all. Remind students of these expectations, particularly for sharing opinions with which others may not agree. In particular, it is important for students not to blame African Americans for the difficult circumstances they faced in working to achieve economic independence after the war and to keep in mind the systemic barriers and the government’s role in failing to support the rights of African Americans which contributed greatly to their limited opportunities.

1. Prepare

Assign students in equal numbers to each of the three options.

2. Present

Ask each group of students to summarize and then articulate the benefits and drawbacks of pursuing their assigned action.

3. Discuss

After discussing the three options described in the sources, ask students to come up with an option not covered in the documents but that they think would have been viable in history. Allow time for students to independently think about an answer. Encourage them to use concrete information from the previous documents, as well as their knowledge of history, in support of their opinions. You can ask them to write down their answer and reason for their choice. If time permits, have students share and discuss these options.

Note: This document refers to Coolie Labor. Coolie labor refers to a system in the 19th century where workers, primarily from Asia, were recruited—often under exploitative and coercive contracts—to perform low-wage, physically demanding jobs, typically on plantations, in mines, and in other labor-intensive industries. This labor system emerged as a replacement for enslaved labor after the abolition of slavery.

_____________________________________________________________________________________

Fellow Citizens:—At a State Labor Convention of the Colored Men of Maryland, held July 20th, 1869, it was unanimously resolved that a National Labor Convention be called to meet in the Union League Hall, City of Washington, D.C., on the 1st Monday in December, 1869, at 12 M., to consider:

1st. The Present Status of Colored Labor in the United States and its Relationship to American Industry.

2nd. To adopt such rules and devise such means as will systematically and effectually organize all the departments of said labor, and make it the more productive in its new Political relationship to Capital, and consolidate the Colored Workingmen of the several States, to act in co-operation with our White Fellow-Workingmen in every State and Territory in the Union, who are opposed to Distinction in the Apprenticeship Laws on account of Color, and to so act cooperatively until the necessity for separate organization shall be deemed unnecessary.

3rd. To consider the question of the importation of Contract Coolie Labor, and to petition Congress for the adoption of such Law as will Prevent its being a system of Slavery,

4th. And to adopt such other means as will best advance the interest of the Colored Mechanic, and Workingmen of the whole country.

Fellow-Citizens: You cannot place too great an estimate upon the important objects this Convention is called to consider, viz: your Industrial Interests. In the greater portion of the United States, Colored Men are excluded from the workshops on account of their color.

The laboring man in a large portion of the Southern States, by a systematic understanding prevailing there, is unjustly deprived of the price of his labor, and in localities far removed from the Courts of Justice is forced to endure wrongs and oppression worse than Slavery.

By falsely representing the laborers of the South, certain interested writers and journals are striving to bring Contract Chinese or Coolie Labor into popular favor there, thus forcing American laborers to work at Coolie wages or starve.

The Address of the National Executive Committee, created by the National Convention of Colored Americans, convened in Washington on the 13th of January, 1869, makes a forcible appeal upon this subject. They have and are making noble efforts to overcome these great wrongs, which we feel can only be effectually remedied by the meeting in National Council of the Mechanics and Laborers of this country. We do, as they have, appeal to the white tradesmen and artisans of this country to conquer their prejudices so far as to enable Colored Men to have a fair field for the display of competitive industry; and with this end in view to do away with all pledges, and obligations that forbid the taking of Colored Boys as Apprentice, to trades, or the employment of Colored Journeymen therein.

Delegates will be admitted without regard to race or color. State or City Convention, will be entitled to send one Delegate for each department of Trade or Labor represented in said Convention. Each Mechanical or Labor Organization in every State and Territory is entitled to be represented by one Delegate. It is hoped that all who feel an interest in the welfare and elevation of our race will take an active part in making this Convention a grand success.

By order of the Executive Committee.--William W. Hare, John W. Locks, Wm. L. James, John H. Tabbs, H. C. Hawkins, Geo. Myers, Robert H. Butler, G. W. Perkins, Wm. Wilks, Geo. Grason, Wesley Howard, Daniel Davis, Jos. Thomas.

J. C. FORTIE, Secretary.

ISAAC MYERS, President.

Source: Reprinted in Foner, Philip S., and Ronald L. Lewis, eds. Black Worker: A Documentary History, Volume II: The Black Worker During the Era of the National Labor Union. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1978. (Document 4.10.10)

As the 1870s progressed, many Black people concluded that the South held no opportunity for them and chose to migrate west.

_______________________________________________________________________________________

An experience of nine years convinces us that it is to the interest of our people. . . to leave this state for some other state or territory more favorable to their material, social and intellectual advancement.

We have labored faithfully since our emancipation for the landed class of Alabama, without receiving adequate compensation, or without the possibility of ever receiving any reasonable remuneration. . . . And consequently, instead of advancing our material interests . . . our condition is becoming worse. . . and many of our people are on the verge of starvation. And inasmuch as there is no prospect of our opportunities being any better. . . we recommend the formation of an association to be called the "Emigration Association of Alabama."

Source: Henry E. Cobb, "The Negro as a Free Laborer in Alabama, 1865-1875,"Midwest Journal, 6 (Fall 1954). Reprinted in Foner, Philip S., and Ronald L. Lewis, eds. Black Worker: A Documentary History, Volume II: The Black Worker During the Era of the National Labor Union. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1978.

Document 4.10.11: Excerpts from “Resolution Adopted by Negro Convention Montgomery, Alabama, December 1, 1874

While some African Americans sought opportunity in the West, others believed that only by returning to Africa could they better their lives. The Liberian Joint Stock Steam Ship Company claimed to have enrolled 150,000 people ready to sail; however, the number who actually left was far smaller.

_______________________________________________________________________________________

Rooms of The Liberia

Joint Stock Steamship Company

Charleston, S.C.

November 6th, 1877

To the President of the Republic of Liberia,

Dear Sir,—This will inform you that the colored people of America and especially of the Southern State, desire to return to their fatherland.

We wish to come bringing our wives and little ones with what wealth and education, arts, and refinement we have been able to acquire in the land of our exile and in the house of bondage. We come pleading in the name of our common Father that our beloved brethren and sisters of the Republic which you have the high and distinguished honor of presiding over, will grant unto us a home with you and yours in the land of our Fathers. We would have addressed you before on this subject, but we have waited to see what would come of the sudden up-heaval of this movement. We are now in position to say, if you will grant us a home in your Republic where we can live and aid in building up a nationality of Africans, we will come, and in coming we will be prepared to take care of ourselves and not be burdensome to the Government. By our present plan of operations, we will be able to furnish food, medicine and clothing to last us for from six months to a year.

We desire to ask you the question, can we come? Will you be able to furnish us with a receptacle, where we could spend the first few weeks of our arrival, or will it be necessary for us to build our own? Would it be convenient for us to settle on the St. Paul's river? We hope to hear your decision at your earliest convenience.

Yours, for and in behalf of 150,000 exiles enrolled for Liberria.

Benj. F.Porter

Pres. Liberia J.S.S.S. Co.

Source: African Repository 53 (1877), 75. Reprinted in Foner, Philip S., and Ronald L. Lewis, eds. Black Worker: A Documentary History, Volume II: The Black Worker During the Era of the National Labor Union. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1978.

Document 4.10.12: “150,000 Exiles Enrolled for Liberia,” November 1877

For a more formal assessment, students could write their opinion on the most viable option for African Americans given the political, economic, and social reality of the late 1870s, supporting their conclusion with at least three concrete pieces of evidence taken from the primary source material that they have examined. The writing could be either a formal persuasive essay or a letter to the editor from the perspective of a person in the 1870s.

Please login or sign up to access the student view functions.