Unit

Years: 1964-1967

Freedom & Equal Rights

Historical Events, Movements, and Figures

Prior to this lesson, students should be familiar with the strategies of the civil rights movement, including the work and philosophy of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. as well as the work of Black nationalists and the Black Power movement. Students should also know the push and pull factors of the Great Migration, and the ways in which racial discrimination manifested in the Northern cities that grew as a result of the influx in Black residents. Studies of redlining and economic discrimination in the Black neighborhoods of Northern cities would complement this lesson.

You may want to consider prior to teaching this lesson: Moving North

African Americans in Northern cities faced widespread political, economic, and social inequality, leading to civil unrest and urban riots in the 1960s. These race riots suggested that the nonviolent civil rights movement was accompanied by other means and methods of change–notably civil unrest and violent protest.

“A riot is the language of the unheard. And what is it that America has failed to hear?” Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. said these words in 1967 in response to the race riots that swept many of America’s northern cities from 1964-1967. Over one hundred riots erupted each year during this period as Black neighborhoods responded to urban poverty and police brutality with widespread civil unrest that was fueled by the summer heat. Jacksonville, Rochester, New York City, Chicago, Philadelphia, Jersey City, Elizabeth, Newark, Paterson – rebellions roiled the East Coast and reached south to Houston and Atlanta, and west to Detroit and Los Angeles. The U. S. attorney general issued a memo to the governors outlining the conditions required by Article IV of the Constitution in order for Federal troops to be requested to suppress local insurrections. Police officers responded violently and often fatally in addition to arresting Black protestors in great numbers. Most of the casualties of the rebellions were African Americans. Few White Americans were killed, injured, or even threatened by the unrest.

The civil unrest were reactions to the living conditions in many 1960s urban Black neighborhoods. The Great Migration had dramatically increased the number of African Americans in Northern cities. However, employment remained scarce and poverty high. According to the Kerner Commission Report of 1968, 11.9% of White Americans lived below the poverty line in 1966, in contrast to 40.6% of African Americans. Civil rights legislation made little difference. Discrimination and redlining concentrated African Americans in poor neighborhoods, infant mortality for people of color ran roughly double the rate for Whites, and the average life expectancy of a Black man was several years less than that of his White counterpart. Crime rates were higher in Black neighborhoods than in White ones, and the police often mistreated African Americans in the neighborhoods they patrolled. For all of these reasons, Black nationalists’ cries for Black Power and self-defense resonated more than the nonviolent principles of Dr. King and others fighting for civil rights in the South.

The civil unrest in the Watts section of Los Angeles seized national attention. On August 11, 1965, a White patrolman stopped a Black driver in Watts. A crowd gathered, there was a scuffle, and the police arrested two Black observers in addition to the driver. Rumors spread quickly that the police had beaten the detainees. That night, rioting began. By the time the unrest ended a week later, 16,000 National Guardsmen and police officers had engaged with an estimated 35,000 people involved in the rebellion. Thirty-four people died and thirty times that number were injured. Police arrested 4,000 people, but not before an estimated $200 million in damage had been done, largely to Black-owned businesses. Martin Luther King, Jr. and the NAACP condemned the violence, and President Lyndon B. Johnson beseeched the nation to respect law and order in the quest for equality.

Johnson’s speech did not prevent unrest in Newark or Detroit, however. White flight had transformed Newark from majority-White to majority-Black between 1960 and 1966, yet the city remained under White leadership. When a Black cab driver was arrested on July 12, 1967, crowds descended on the police station and threw rocks and Molotov cocktails. White police fired their weapons into stores that were largely Black-owned. By the time the rebellion subsided on July 17, twenty-three people had been killed. All but two were Black. Five days later, Detroit exploded after police raided a Black club, sparking more unrest. Unprepared for riot control, the police and National Guardsmen fired thousands of rounds, killing thirty of the forty-three people who died according to the Kerner Commission. (Rioters themselves caused two or three of the deaths.) Paratroopers from the 101st Airborne Division helped quell the disturbances. This was the first time federal troops had been deployed for that purpose since the 1943 Detroit riot. Violence finally ebbed on July 27.

Just as multiple factors contributed to the urban unrest of the 1960s, no single reason explains the tenuous end to the unrest. Black people recognized that the violence was self-destructive: Loss of life and damage to property was greatest in African American communities. Some historians suggest that the anger that sparked the riots turned into despair as African Americans began to fear that neither peaceful nor violent protests would bring about change.

President Johnson assembled the Kerner Commission to analyze the causes of the civil unrest and to offer suggestions to prevent further violence. The Kerner Report identified that “White racism is essentially responsible for the explosive mixture which has been accumulating in our cities since the end of World War II.”. It further went on to suggest that the government pass reforms in education, healthcare, and employment to address racial inequality in American cities. Some cities recruited people of color into their police forces, and neighborhood committees emerged to facilitate communication with law enforcement. Yet White backlash against these responses undercut progress, and today’s cities continue to face many of the same problems of the 1960s.

Bean, Jonathan J. “‘Burn, Baby, Burn:’ Small Businesses in the Urban Riots of the 1960s.” The Independent Review. Vol. 2, no.2 (Fall 2000). 165-187.

Bergesen, Albert. “Race Riots of 1967: An Analysis of Police Violence in Detroit and Newark.” Journal of Black Studies, vol. 12, no. 3, 1982, pp. 261–74. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/2784247. Accessed 18 Mar. 2023.

Brazil, Noli. “Large-Scale Urban Riots and Residential Segregation: A Case Study of the 1960s U.S. Riots.” Demography, vol. 53, no. 2, 2016, pp. 567–95. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24757068. Accessed 18 Mar. 2023.

Casey, Marcus, and Bradley Hardy. “50 Years After the Kerner Commission Report, the Nation Is Still Grappling with Many of the Same Issues.” Brookings, Brookings, 9 Mar. 2022, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/up-front/2018/09/25/50-years-after-the-kerner-commission-report-the-nation-is-still-grappling-with-many-of-the-same-issues/.

“Encyclopedia of Detroit: Uprising of 1967” Detroit Historical Society, https://detroithistorical.org/learn/encyclopedia-of-detroit/uprising-1967.

George, Alice. “The 1968 Kerner Commission Got It Right, but Nobody Listened.” Smithsonian, Smithsonian Magazine, 1 Mar. 2018, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/1968-kerner-commission-got-it-right-nobody-listened-180968318/.

Perez, Anthony Daniel, et al. “Police and Riots, 1967-1969.” Journal of Black Studies, vol. 34, no. 2, 2003, pp. 153–82. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3180902. Accessed 18 Mar. 2023.

Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders [Kerner Commission Report]. New York Times Edition. E.P. Dutton & Co., Inc.: New York, 1968.

Theoharis, Jeanne. “The northern promised land that wasn’t”: Rosa Parks and the Black Freedom Struggle in Detroit, OAH Magazine of History, Volume 26, Issue 1, January 2012, Pages 23–27, https://doi.org/10.1093/oahmag/oar054

“Watts Rebellion (Los Angeles).” The Martin Luther King, Jr., Research and Education Institute, 5 June 2018, https://kinginstitute.stanford.edu/encyclopedia/watts-rebellion-los-angeles.

Language is important when discussing civil unrest, as the words “rioter” and “looter” can come with racialized connotations from the media and should be contextualized for students. Consider using terms such as “rebellion” or “civil unrest” instead, and have a conversation with students about the terminology you use. While the civil unrest of the 1960s was violent, it’s important to emphasize and evaluate the causes of that violence–rampant racial inequality. Discussions and images of racial violence and police brutality may trigger emotional responses for students, so it is important to be proactive and sensitive to student reactions to images, especially images of police violence.

We recommend having a conversation with students about the ways in which the language we use about race has changed since the Kerner Commission. Many primary documents of the time period contain references to “negro” or “negroes”. It will be helpful to clarify that students should be mindful of the language that they use to discuss the past when terms differ from what is most appropriate to use today.

From 1910-1970, over six million African Americans fled oppression in the South by moving North and West in the Great Migration. Vibrant Black communities boomed in cities such as New York City, Detroit, Cleveland, Chicago, Newark, and Los Angeles, among others. However, Black residents of Northern cities faced racial inequality of a different sort. Discriminatory housing policies and high unemployment levels led to high levels of poverty in majority-Black neighborhoods, police brutality against African Americans was commonplace, and major social, political, and economic disparities remained.

While the nonviolent civil rights movement gained momentum in the South, African Americans in urban areas had limited options to fight for change. Civil unrest–including violent protests, rebellions, and riots–broke out across several cities between 1964 and 1967, fueled by simmering frustration and the summer heat. The rebellions were incredibly destructive; hundreds of people died–mostly African Americans–thousands were arrested, many Black-owned businesses were damaged, and in some cases the National Guard had to intervene.

While several instances of police brutality were the immediate cause of the riots, the U.S. government created a panel called the Kerner Commission to investigate the underlying factors of the unrest and make policy recommendations to avoid future rebellions. The Kerner Report identified that “White racism is essentially responsible for the explosive mixture which has been accumulating in our cities since the end of World War II.”. It further went on to suggest that the government pass reforms in education, healthcare, and employment to address racial inequality in American cities. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. said: “A riot is the language of the unheard. And what is it that America has failed to hear?” In this unit of study, you will attempt to answer this very question, and you will consider if the Kerner Commission’s findings are still relevant today.

Student Handout:

Select the activities and sources you would like to include in the student view and click “Launch Student View.”

It is highly recommended that you review the Teaching Tips and sources before selecting the activities to best meet the needs and readiness of your students. Activities may utilize resources or primary sources that contain historical expressions of racism, outdated language or racial slurs.

Explain to students that they will examine several primary sources that document city life in both Black and White neighborhoods during the 1960s in an effort to understand the root causes of urban rebellions. For each document type below, students should consider the following questions:

Instruct students to work in a small group to create a flier for a community meeting that aims to address the inequality in Northern cities of the 1960s. Groups should each make a one-page flier encouraging residents to attend the community meeting, and fliers should reference details from the Kerner Commission Report. End by having the groups share their fliers with the class.

Instruct students to independently read Chapter 17 of the Kerner Commission Report, which contains recommendations for national action that could resolve the issues leading to the urban unrest of the 1960s. After they read, students should write down their main takeaway from the document and create three discussion questions they want to ask the full class during a Socratic seminar.

After the seminar, lead a reflection in which students answer the following questions:

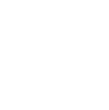

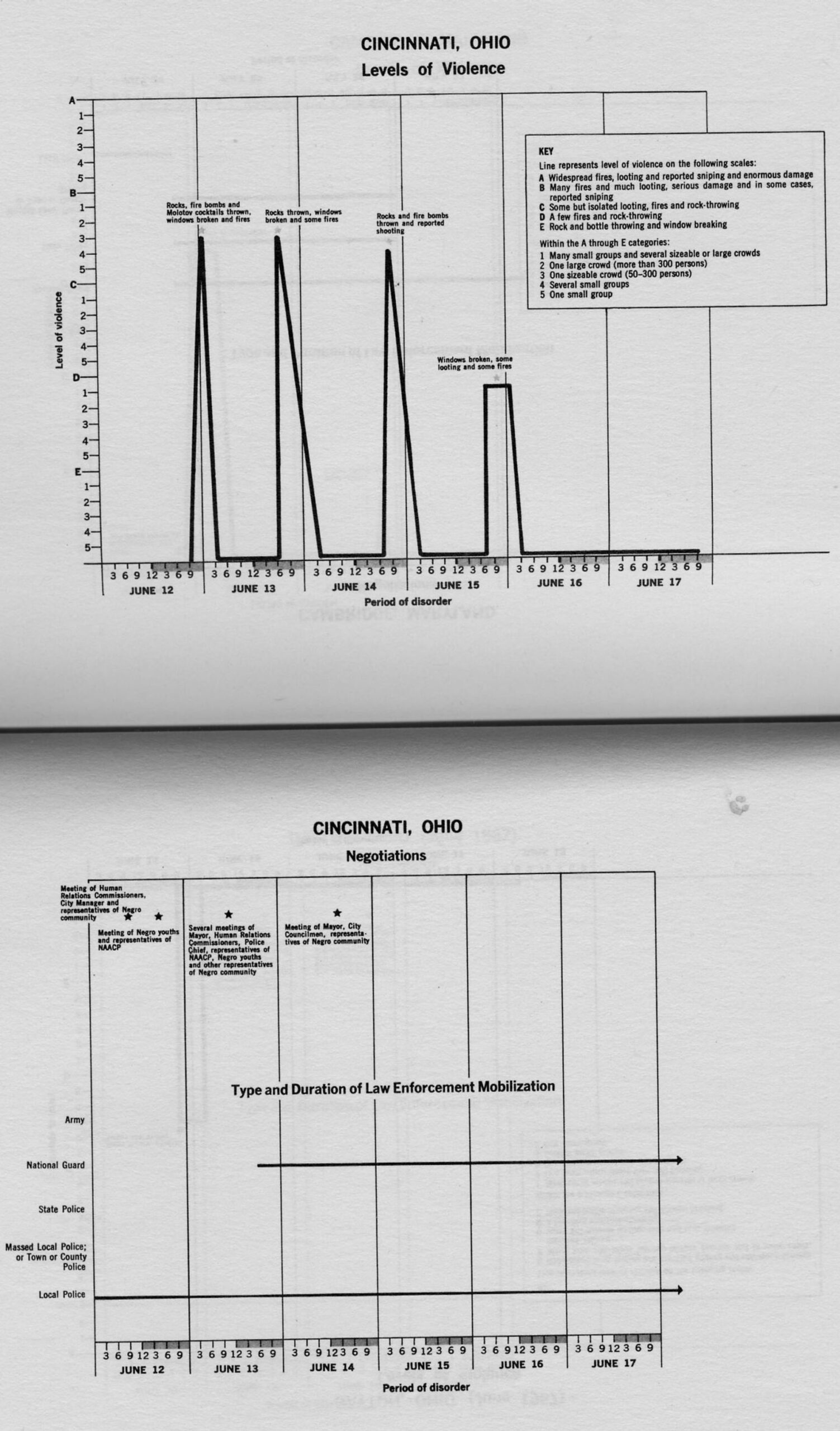

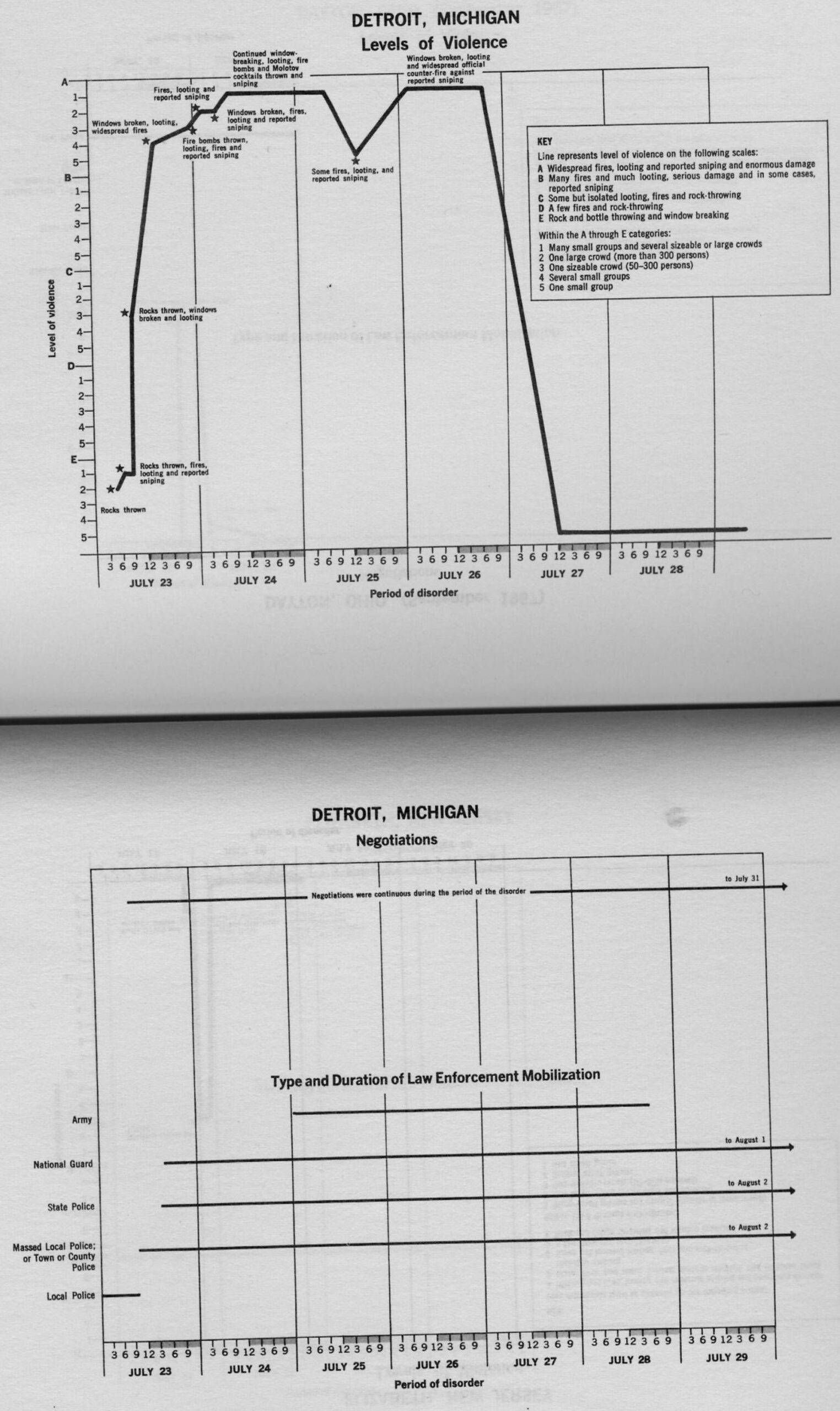

For background information, distribute the Introduction to the Kerner Commission Report. Students should read it individually. Next, distribute the charts on the Cincinnati Rebellion Chart and the Detroit Rebellion Chart. Working in pairs, students should analyze each chart and be able to answer the following questions for Cincinnati (typifying a serious but minor rebellion) and Detroit (typifying a major rebellion).

As a full class, lead a discussion to compare and contrast the two case studies. Consider the following questions:

Excerpts from the introduction to the Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders [Kerner Commission Report], 1968

The Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, also known as the Kerner Commission Report after the commission’s chairman, Otto Kerner, Governor of Illinois, investigated the riots in the cities of the 1960s. President Johnson assembled the commission after the Detroit riot of 1967. It consisted mainly of white, moderate, male politicians. Roy Wilkins of the NAACP was included, as was the President of the United Steelworkers of America and the Atlanta Chief of Police. The commission described the riots in a variety of cities; their causes, both proximate and historical; the handling of the riots at all levels of government; and recommended a wide range of social reforms.

The “typical” riot did not take place. The disorders of 1967 were unusual, irregular, complex and unpredictable social processes. Like most human events, they did not unfold in an orderly sequence. However, an analysis of our survey information leads to some conclusions about the riot process.

In general:

We have seen what happened. Why did it happen?

In addressing this question, we shift our focus from the local to the national scene, from the particular events of the summer of 1967 to the factors within the society at large which have brought about the sudden violent mood of so many urban Negroes.

These factors are both complex and interacting; they vary significantly in their effect from city to city and from year to year; and the consequences of one disorder, generating new grievances and new demands, becomes the causes of the next. It is this which creates the “thicket of tension, conflicting evidence and extreme opinions” cited by the President.

Despite these complexities, certain fundamental matters are clear. Of these, the most fundamental is the racial attitude and behavior of white Americans toward black Americans.

Race prejudice has shaped our history decisively; it now threatens to affect our future.

White racism is essentially responsible for the explosive mixture which has been accumulating in our cities since the end of World War II. Among the ingredients of this mixture are:

At the same time, most white and some Negroes outside the ghetto have prospered to a degree unparalleled in the history of civilization. Through television and other media, this affluence has been flaunted before the eyes of the Negro poor and the jobless ghetto youth.

Yet these facts alone cannot be said to have caused the disorders. Recently, other powerful ingredients have begun to catalyze the mixture:

* * *

To this point, we have attempted to identify the prime components of the “explosive mixture.” In the chapters that follow we seek to analyze them in the perspective of history. Their meaning, however, is clear:

In the summer of 1967, we have seen in our cities a chain reaction of racial violence. If we are heedless, none of us shall escape the consequences.

Document 5.22.4

Place students in small groups, and assign each group a photograph from Life Magazine Photos of the 1967 Detroit Riot. Students should work as a team to list 10 observations about the photograph. Each group should also write a one-sentence story of their photograph. Then, ask the groups to share their one-sentence stories with the full class. End by asking students to come up with a question they have as a result of analyzing their group’s photo.

Distribute the Excerpt of President Johnson’s Statement on the Riots in Watts and read it aloud as a class. Then students should work with a partner to complete a concept web of the statement. In the center should go “Watts rebellions.” Four branches should connect to it: Johnson’s emotional reaction, his explanation of the causes of the rebellion, his opinion on whether the rebellion was right or wrong and why, and finally, his solution to the problem. For each main branch, students should include a quotation to support their answer.

Statement on the Riots in Watts by President Lyndon B. Johnson, August 20, 1965

If there is one thing I think we have learned from the civil rights struggle, it is that the problem of bringing the Negro American into an equal role in our society is more complex, and is more urgent, and is much more critical than any of us have ever known. Who of you could have predicted 10 years ago, that in this last, sweltering, August week thousands upon thousands of disenfranchised Negro men and women would suddenly take part in self government, and that thousands more in that same week would strike out in an unparalleled act of violence in this Nations.

Our conscience cries out against the hatred that we heard last week. It bore no relation to the orderly struggle for civil rights that has ennobled the last decade. Every leader in that struggle has condemned this outrage against the laws of the land. And during the few days that preceded it, I had spent all week at the White House visiting individually with Dr. King, Mr. Farmer, Dr. Roy Wilkins, Mr. Philip Randolph—all talking about the great meeting that we had to have here later in the fall, because the cities of this Nation and the Negro family in this Nation are two of our most pressing, most important problems. Well, the bitter years that preceded the riots, the death of hope where hope existed, their sense of failure to change the conditions of life—these things no doubt led to these riots. But they did not justify them.

I hope that every American who believes in equal opportunity for his fellow men, understands this distinction that I have made. For we shall never achieve a free and prosperous and hopeful society until we have suppressed the fires of hate and we have turned aside from violence—whether that violence comes from the nightriders of the Klan, or the snipers and the looters in the Watts district Neither old wrongs nor new fears can ever justify arson or murder....

With . . . rights comes responsibility.

And with responsibility there goes obligation.

We cannot, and we must not, in one breath demand laws to protect the rights of all of our citizens, and then turn our back, or wink, or in the next breath allow laws to be broken that protect the safety of our citizens. There just must never come the hour in this Republic when any citizen, whoever he is, can ever ignore the law or break the law with impunity.

And so long as I am your President I intend to preserve the rights of all of our citizens, and I intend to enforce the laws that protect all of our citizens— without regard to race, religion, region, or without fear or favor.

A rioter with a Molotov cocktail in his hands is not fighting for civil rights any more than a Klansman with a sheet on his back and a mask on his face. They are both more or less what the law declares them: lawbreakers, destroyers of constitutional rights and liberties, and ultimately destroyers of a free America. They must be exposed and they must be dealt with.

It is our duty—and it is our desire—to open our hearts to humanity's cry for help. It is our obligation to seek to understand what could lie beneath the flames b that scarred that great city. So let us equip the poor and the oppressed—let us equip them for the long march to dignity and to wellbeing. But let us never confuse the need for decent work and fair treatment with an excuse to destroy and to uproot.

Ours is an open society. The world is always witness to whatever we do—sometimes, I think (results of the cooperation of some of my friends) to some things we don't do. We would not have it otherwise. For the brave story of the Negro American is related to the struggle of men on every continent for their rights as sons of God. It is a compound of brilliant promises and stunning reverses. Sometimes, as in the past week

when the two are mixed on the same pages of our newspapers and television screens, e result is baffling to all the world. And is baffling to me, and to you, and to us. .nd always there is the danger that hours of disorder may erase the accumulated goodwill of many months and many years. And warn and plead with all thinking Americans to contemplate this for a due period.

Yet beneath the discord we hear another theme. That theme speaks of a day when Americans of every color, and every creed, and every religion, and every region, and every sex can be trained for decent employment, can find it, can secure it, can have it preserved, and can support their families in an enriching and a rewarding environment....

Source: “On the 1965 Watts Riots” Johnson, Lyndon. 1965

www.multied.com/documents/LBJwatts.html

Document 5.22.3

Note: This activity requires knowledge from Activity 6.

Instruct students to independently read the Excerpt of President Johnson’s Statement on the Riots in Watts and the Introduction to the Kerner Commission Report. Then in small groups have students discuss the following questions:

Statement on the Riots in Watts by President Lyndon B. Johnson, August 20, 1965

If there is one thing I think we have learned from the civil rights struggle, it is that the problem of bringing the Negro American into an equal role in our society is more complex, and is more urgent, and is much more critical than any of us have ever known. Who of you could have predicted 10 years ago, that in this last, sweltering, August week thousands upon thousands of disenfranchised Negro men and women would suddenly take part in self government, and that thousands more in that same week would strike out in an unparalleled act of violence in this Nations.

Our conscience cries out against the hatred that we heard last week. It bore no relation to the orderly struggle for civil rights that has ennobled the last decade. Every leader in that struggle has condemned this outrage against the laws of the land. And during the few days that preceded it, I had spent all week at the White House visiting individually with Dr. King, Mr. Farmer, Dr. Roy Wilkins, Mr. Philip Randolph—all talking about the great meeting that we had to have here later in the fall, because the cities of this Nation and the Negro family in this Nation are two of our most pressing, most important problems. Well, the bitter years that preceded the riots, the death of hope where hope existed, their sense of failure to change the conditions of life—these things no doubt led to these riots. But they did not justify them.

I hope that every American who believes in equal opportunity for his fellow men, understands this distinction that I have made. For we shall never achieve a free and prosperous and hopeful society until we have suppressed the fires of hate and we have turned aside from violence—whether that violence comes from the nightriders of the Klan, or the snipers and the looters in the Watts district Neither old wrongs nor new fears can ever justify arson or murder....

With . . . rights comes responsibility.

And with responsibility there goes obligation.

We cannot, and we must not, in one breath demand laws to protect the rights of all of our citizens, and then turn our back, or wink, or in the next breath allow laws to be broken that protect the safety of our citizens. There just must never come the hour in this Republic when any citizen, whoever he is, can ever ignore the law or break the law with impunity.

And so long as I am your President I intend to preserve the rights of all of our citizens, and I intend to enforce the laws that protect all of our citizens— without regard to race, religion, region, or without fear or favor.

A rioter with a Molotov cocktail in his hands is not fighting for civil rights any more than a Klansman with a sheet on his back and a mask on his face. They are both more or less what the law declares them: lawbreakers, destroyers of constitutional rights and liberties, and ultimately destroyers of a free America. They must be exposed and they must be dealt with.

It is our duty—and it is our desire—to open our hearts to humanity's cry for help. It is our obligation to seek to understand what could lie beneath the flames b that scarred that great city. So let us equip the poor and the oppressed—let us equip them for the long march to dignity and to wellbeing. But let us never confuse the need for decent work and fair treatment with an excuse to destroy and to uproot.

Ours is an open society. The world is always witness to whatever we do—sometimes, I think (results of the cooperation of some of my friends) to some things we don't do. We would not have it otherwise. For the brave story of the Negro American is related to the struggle of men on every continent for their rights as sons of God. It is a compound of brilliant promises and stunning reverses. Sometimes, as in the past week

when the two are mixed on the same pages of our newspapers and television screens, e result is baffling to all the world. And is baffling to me, and to you, and to us. .nd always there is the danger that hours of disorder may erase the accumulated goodwill of many months and many years. And warn and plead with all thinking Americans to contemplate this for a due period.

Yet beneath the discord we hear another theme. That theme speaks of a day when Americans of every color, and every creed, and every religion, and every region, and every sex can be trained for decent employment, can find it, can secure it, can have it preserved, and can support their families in an enriching and a rewarding environment....

Source: “On the 1965 Watts Riots” Johnson, Lyndon. 1965

www.multied.com/documents/LBJwatts.html

Document 5.22.3

Excerpts from the introduction to the Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders [Kerner Commission Report], 1968

The Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, also known as the Kerner Commission Report after the commission’s chairman, Otto Kerner, Governor of Illinois, investigated the riots in the cities of the 1960s. President Johnson assembled the commission after the Detroit riot of 1967. It consisted mainly of white, moderate, male politicians. Roy Wilkins of the NAACP was included, as was the President of the United Steelworkers of America and the Atlanta Chief of Police. The commission described the riots in a variety of cities; their causes, both proximate and historical; the handling of the riots at all levels of government; and recommended a wide range of social reforms.

The “typical” riot did not take place. The disorders of 1967 were unusual, irregular, complex and unpredictable social processes. Like most human events, they did not unfold in an orderly sequence. However, an analysis of our survey information leads to some conclusions about the riot process.

In general:

We have seen what happened. Why did it happen?

In addressing this question, we shift our focus from the local to the national scene, from the particular events of the summer of 1967 to the factors within the society at large which have brought about the sudden violent mood of so many urban Negroes.

These factors are both complex and interacting; they vary significantly in their effect from city to city and from year to year; and the consequences of one disorder, generating new grievances and new demands, becomes the causes of the next. It is this which creates the “thicket of tension, conflicting evidence and extreme opinions” cited by the President.

Despite these complexities, certain fundamental matters are clear. Of these, the most fundamental is the racial attitude and behavior of white Americans toward black Americans.

Race prejudice has shaped our history decisively; it now threatens to affect our future.

White racism is essentially responsible for the explosive mixture which has been accumulating in our cities since the end of World War II. Among the ingredients of this mixture are:

At the same time, most white and some Negroes outside the ghetto have prospered to a degree unparalleled in the history of civilization. Through television and other media, this affluence has been flaunted before the eyes of the Negro poor and the jobless ghetto youth.

Yet these facts alone cannot be said to have caused the disorders. Recently, other powerful ingredients have begun to catalyze the mixture:

* * *

To this point, we have attempted to identify the prime components of the “explosive mixture.” In the chapters that follow we seek to analyze them in the perspective of history. Their meaning, however, is clear:

In the summer of 1967, we have seen in our cities a chain reaction of racial violence. If we are heedless, none of us shall escape the consequences.

Document 5.22.4

Divide the class into three groups. The first group of two or three students forms a congressional panel. The remaining students are split in half. One half should support the position that the urban rebellions of the 1960s were justified, using documents already examined to prove their argument. The other half should argue that the rebellions were unjustified, also using evidence from primary sources. The congressional panel, after hearing each side, should render a decision supported with the strengths or weaknesses of the opposing sides’ arguments, and create a list of recommendations to prevent future unrest. The teacher may want to allow time for additional research by each group or have groups work with the documents already examined before the groups present their arguments.

Instruct students to work in small groups to answer the research question: to what extent were the urban rebellions of the 1960s effective in addressing racial inequality? Students should produce a presentation that answers this question, referencing at least three primary sources and at least two secondary sources by historians. Teachers may direct students to the further resources below as a starting point. Groups should then present to the full class. Facilitate a closing discussion using the following questions:

Please login or sign up to access the student view functions.