Unit

Years: 1865–1876

Economy & Society

Historical Events, Movements, and Figures

Prior to this lesson, students should be familiar with the history of enslavement in the United States and the ideology of White supremacy that was used to justify enslaving Black people. Students should have knowledge of the causes of the Civil War, the Emancipation Proclamation, and the role of Black troops in the Union war effort.

Students should understand the significance of voting rights in a democratic society.

You may want to consider prior to teaching this lesson: The Freedman’s Bureau

Voting rights for African American men were achieved through the efforts of African Americans fighting for their constitutional rights, as well as the political dynamics of the Reconstruction era. While Republicans sought to secure meaningful equality for freedpeople, Southern Democrats aimed to re-subjugate African Americans. This increased political power for African Americans was met with backlash, as the ideology of White supremacy persisted, unaddressed.

Voting rights for African American men were achieved through the efforts of African Americans fighting for their constitutional rights, as well as the political dynamics of the Reconstruction era. While Republicans sought to secure meaningful equality for freedpeople, Southern Democrats aimed to deny African Americans civil rights and limit their opportunities.

The Cases for Suffrage

When the Civil War ended in April 1865, the fate of African Americans remained uncertain as the rights of citizenship did not accompany the Emancipation Proclamation executive order. The freedpeople fervently and urgently held to the understanding that they were entitled to all the rights of free citizens in a democracy. In events held in the southern states shortly after the war, such as the Freedmen’s Conventions and Homestead Act Conventions, African Americans voiced their concerns, strategized, and made efforts to mobilize to secure their rights as citizens. Yet African Americans continued to reckon with the reality of a society unwilling to respond in both word and deed. Thus, the right to suffrage was integral to ensuring rights and representation for African Americans, as it provided a means to influence policies and secure protections under the law.

African American suffrage also held importance and urgency for members of the Republican Party. The Republican party, founded in the 1850s as a party opposed to the expansion of slavery, included many early members who were abolitionists. Abolitionist members of the Republican party believed strongly in the rights of African Americans. They held that the end of slavery, without civil rights, left freedpeople enslaved in all but name. For other Republicans, there was a growing acknowledgment that their grip on Congress was tenuous and the enfranchisement of African Americans was a way to gain political support. By granting voting rights to African American men, these Republicans hoped to secure support for their party and its policies. Though disparate, these beliefs brought Republicans together and led them to join forces with African Americans in taking measures to ensure male suffrage.

However, full citizenship and representation seemed unlikely as President Andrew Johnson’s plan for Reconstruction began to formalize.

Johnson believed that “white men alone must manage the South.” As a result, many officials who had once served in the rebel government were allowed to be reelected to the newly reconstructed state governments, including nine former Confederate congressmen.

Johnson’s Reconstruction plan also permitted the former Confederate states to re-enter the Union under lenient provisions. Emboldened by Johnson’s lenience, the former Confederates returned to office, and southern state governments began openly repudiating federal authority. These reconstructed state governments formed from 1865-66 drafted a series of laws known as Black Codes, which continued to limit the civil rights of the freedpeople, denying them the right to serve on juries, limiting their access to the courts, and strictly controlling the terms of their labor.

Military Reconstruction Acts of 1867

Despite President Johnson’s opposition, one of the most important measures the Republican-controlled Congress took up following the Civil War in relation to male suffrage was the Military Reconstruction Acts of 1867. The acts were intended to formally reorganize the Southern states that had seceded from the Union and to establish conditions for their readmission into the United States. Under these acts, the former Confederate states (except for Tennessee) were to be taken out of the Union and placed under the temporary rule of military governors.

Three key requirements of the Military Reconstruction Acts of 1867 were:

Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendment

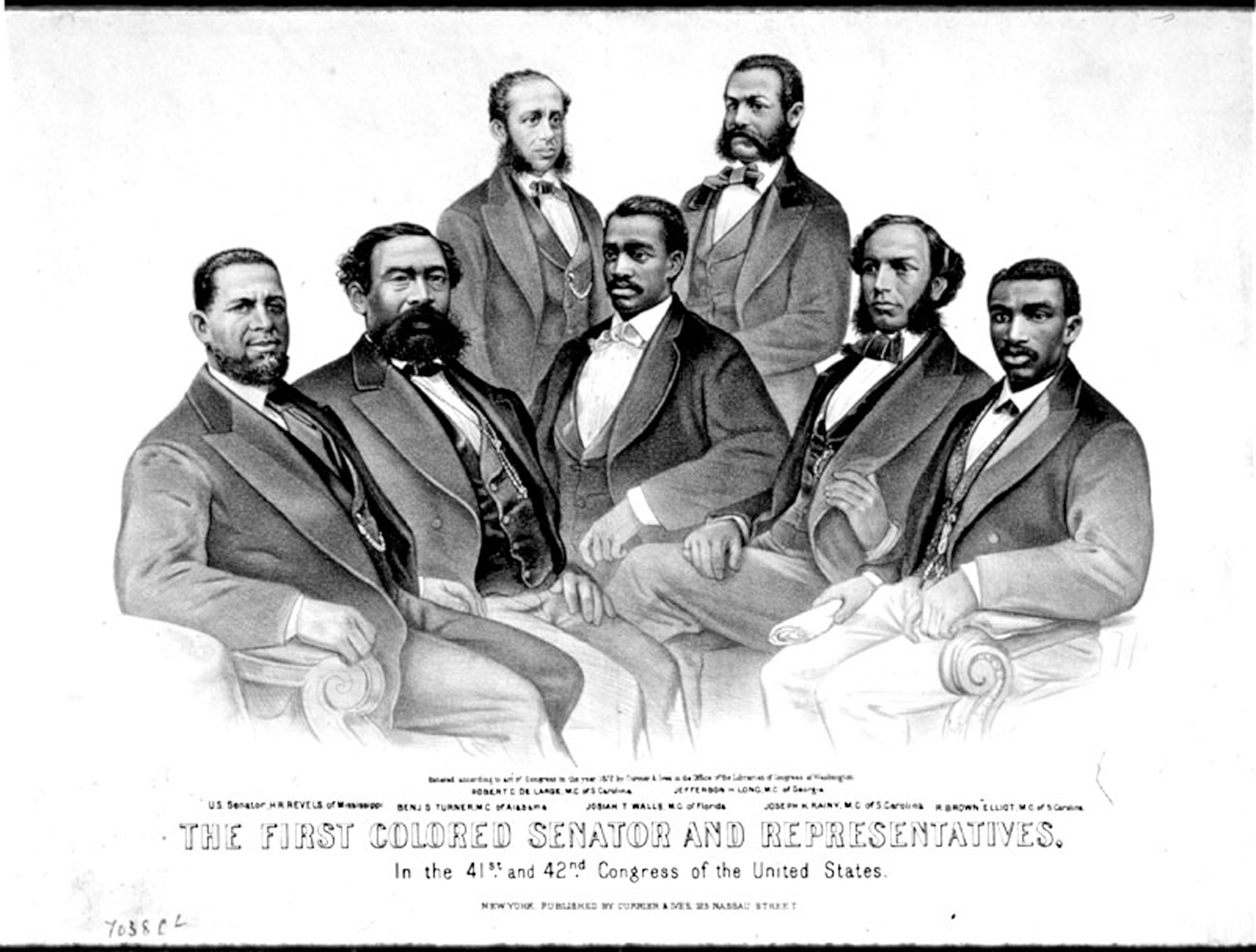

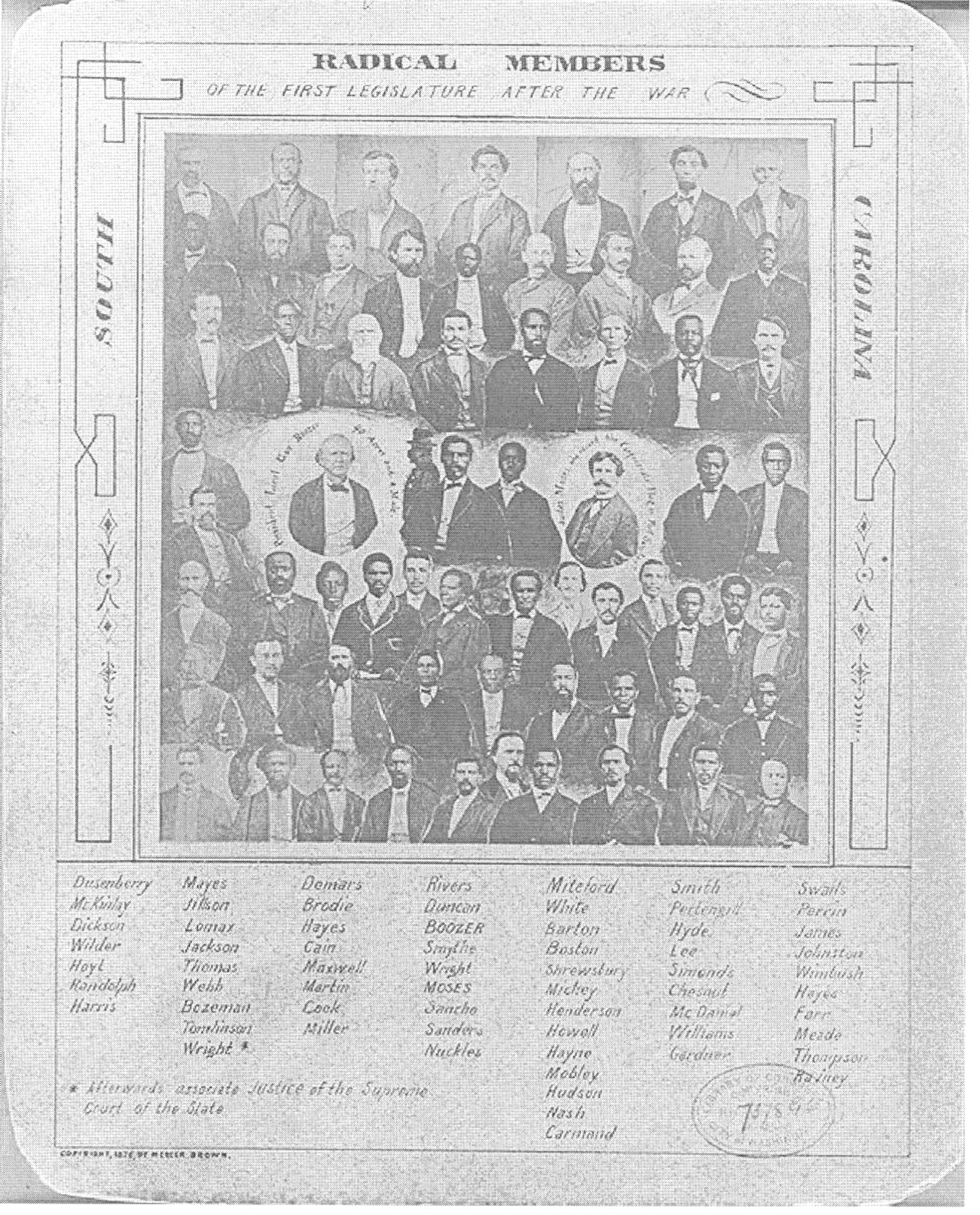

The new state governments became the nation’s first meaningful experiment in interracial (involving members of different racial groups) democracy. African Americans were represented through their votes, which tended to go to the Republican Party. They were also represented directly. For the first time, large numbers of African Americans were elected to office. As part of the Military Reconstruction Acts, new state constitutional conventions were called in each of the ten states to ratify the Fourteenth Amendment.

Specifically, the Fourteenth Amendment, ratified in 1868, defined citizenship, stating that all persons born or naturalized in the United States are citizens of the country and of their respective states and that states cannot infringe on the rights and privileges of U.S. citizens. This guaranteed the citizenship rights of African Americans. In 1869, shortly after the new governments were formed, Congress began moving the Fifteenth Amendment forward. The 15th Amendment to the United States Constitution, ratified in 1870 included the language that “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” thus firmly granting African American men the right to vote.

The End of Reconstruction Governments

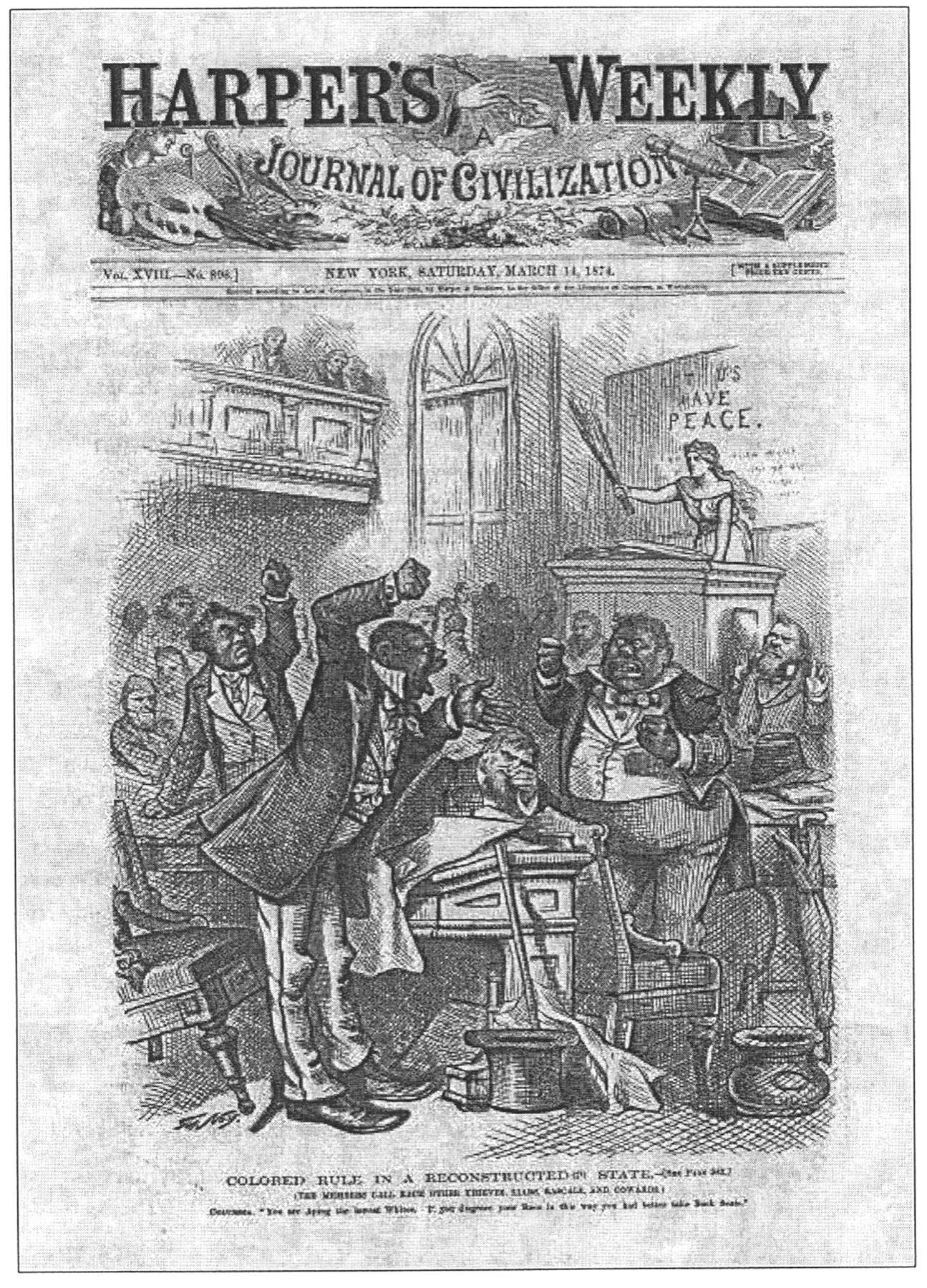

The newly elected interracial Republican state governments in the South were met with a strong backlash. Former Confederates and White supremacists attacked them immediately, targeting African American voters and politicians in particular. Southern Democrats and their supporters claimed that the presence of “ignorant” formerly enslaved people in the voting populace led to a “tragic era” of corruption and misrule. A concerted campaign of voting fraud, terror, and violence led up to the presidential election of 1876.

In the 1876 election, Rutherford Hayes was the Republican candidate, and Samuel Tilden was the Democratic candidate. The election results were contested, and Hayes agreed to the Compromise of 1877, also known as the Hayes-Tilden Compromise or the Electoral Commission Act. This compromise was a series of informal agreements and understandings reached between representatives of the Republican and Democratic parties. Under this compromise, Hayes would be awarded the presidency. In return, Hayes agreed to several concessions sought by Southern Democrats, including the withdrawal of federal troops from the South and an end to federal intervention in Southern state politics. The withdrawal of federal troops allowed Southern Democrats to regain control of state governments across the South. As the rights of the amendments could not be ignored, in order to continue to disenfranchise African Americans other efforts like the Jim Crow laws and voter intimidation and voter suppression actions such as literacy tests and poll taxes began.

Teaching Activities: Reconstruction Period: 1865-1876, Zinn Education Project

Videos & Lesson Plans: The Reconstruction Era and the Fragility of Democracy, Facing History and Ourselves

Videos & Lesson Plans: Reconstruction: America After the Civil War. PBS.

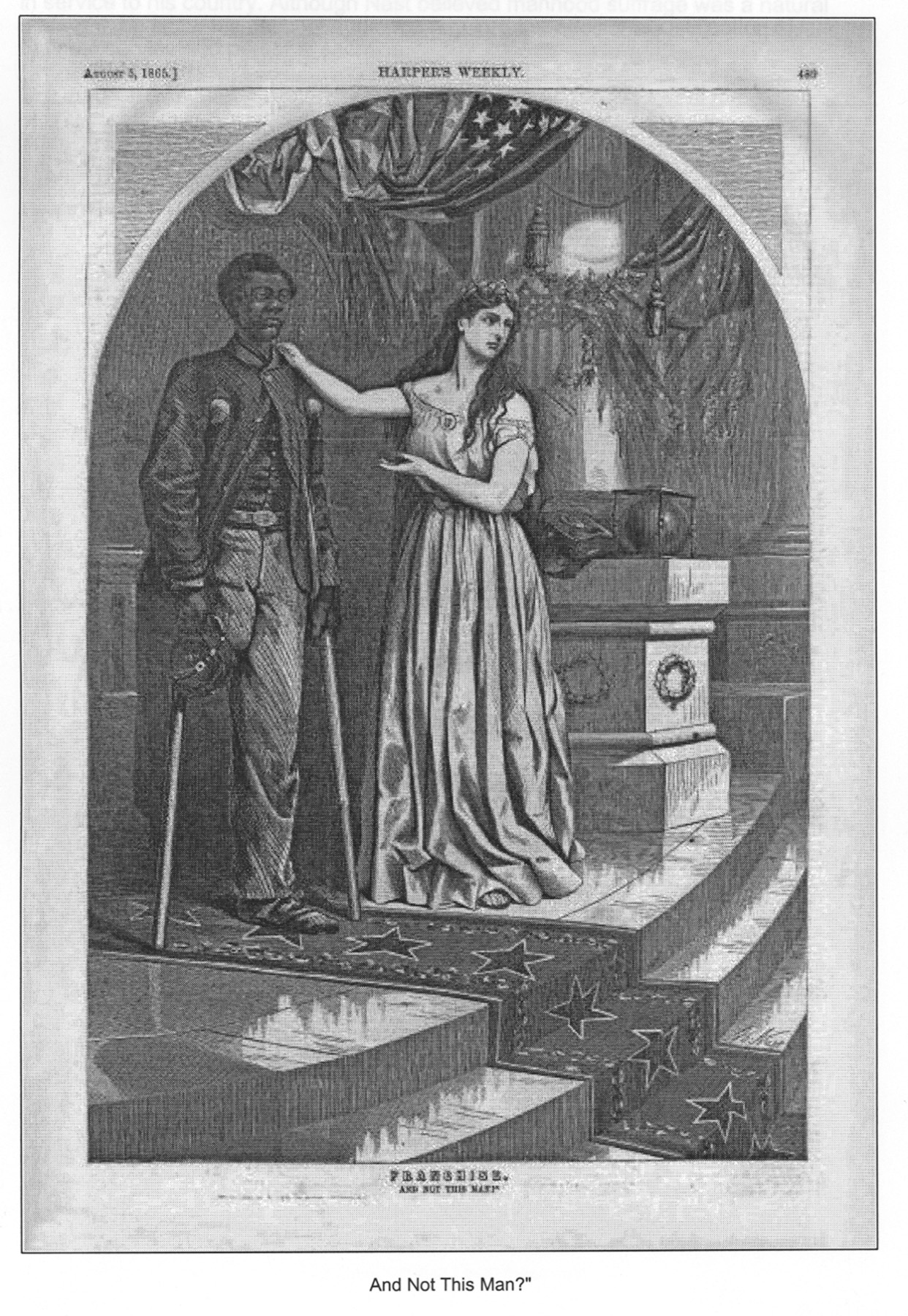

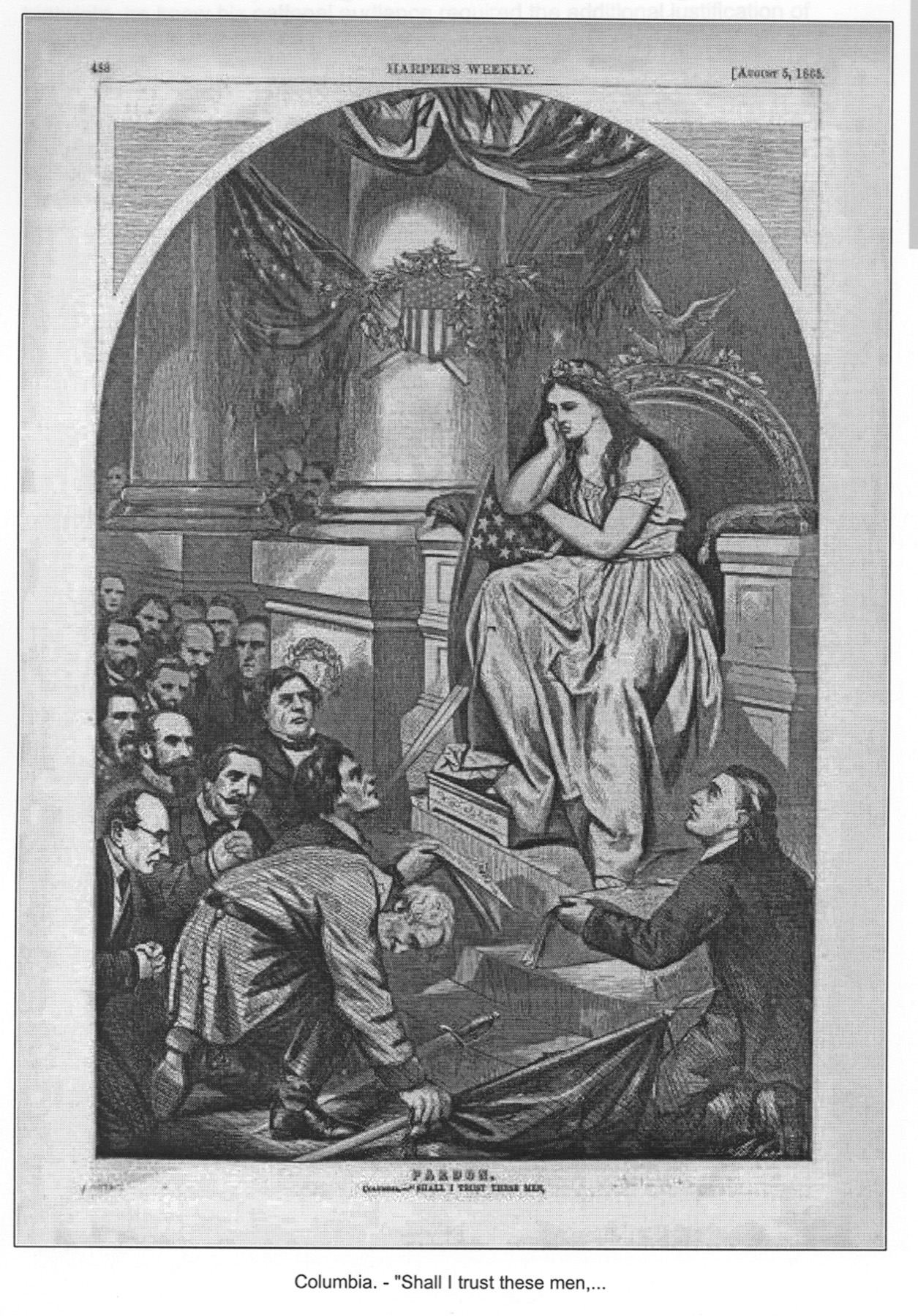

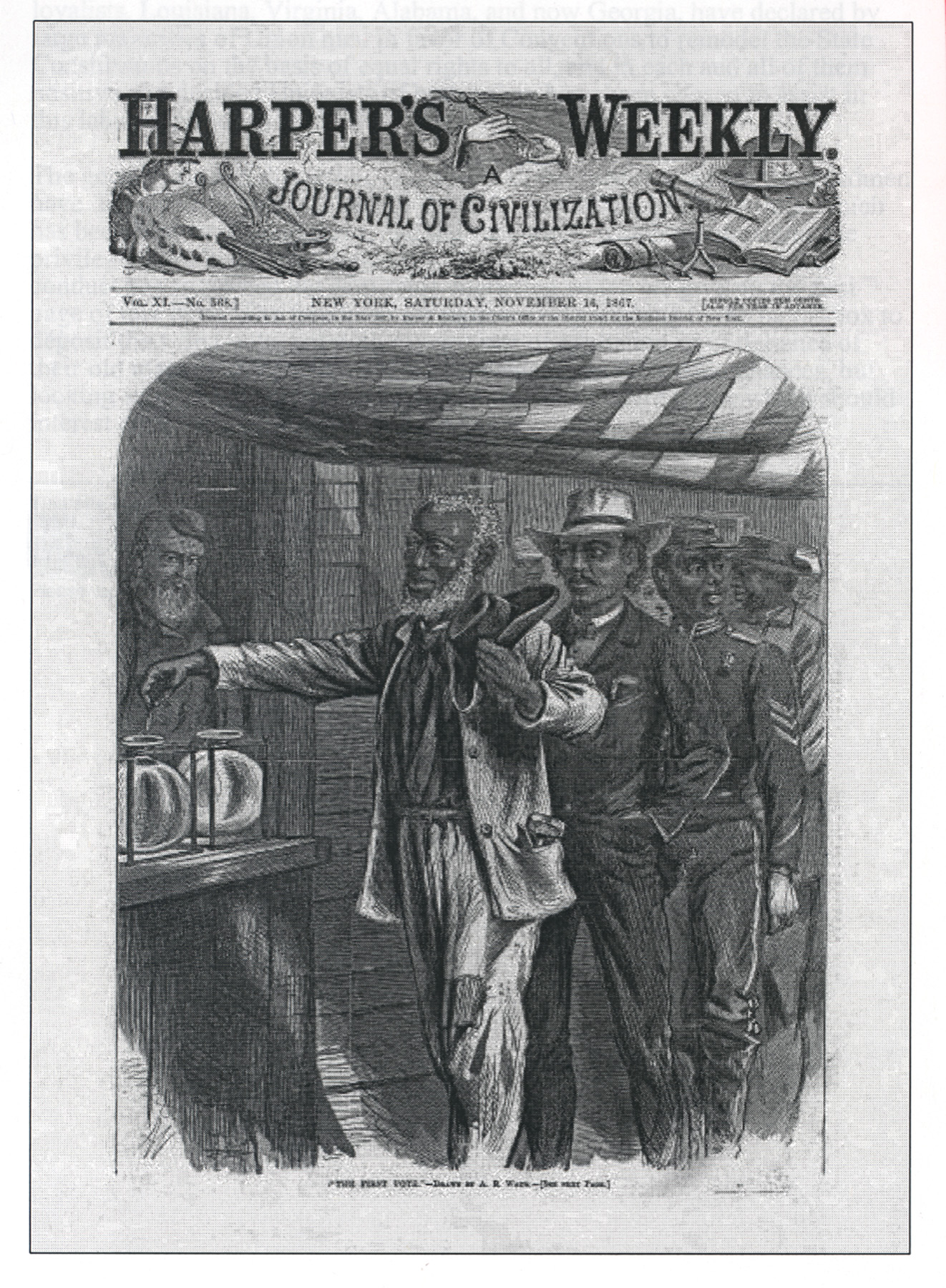

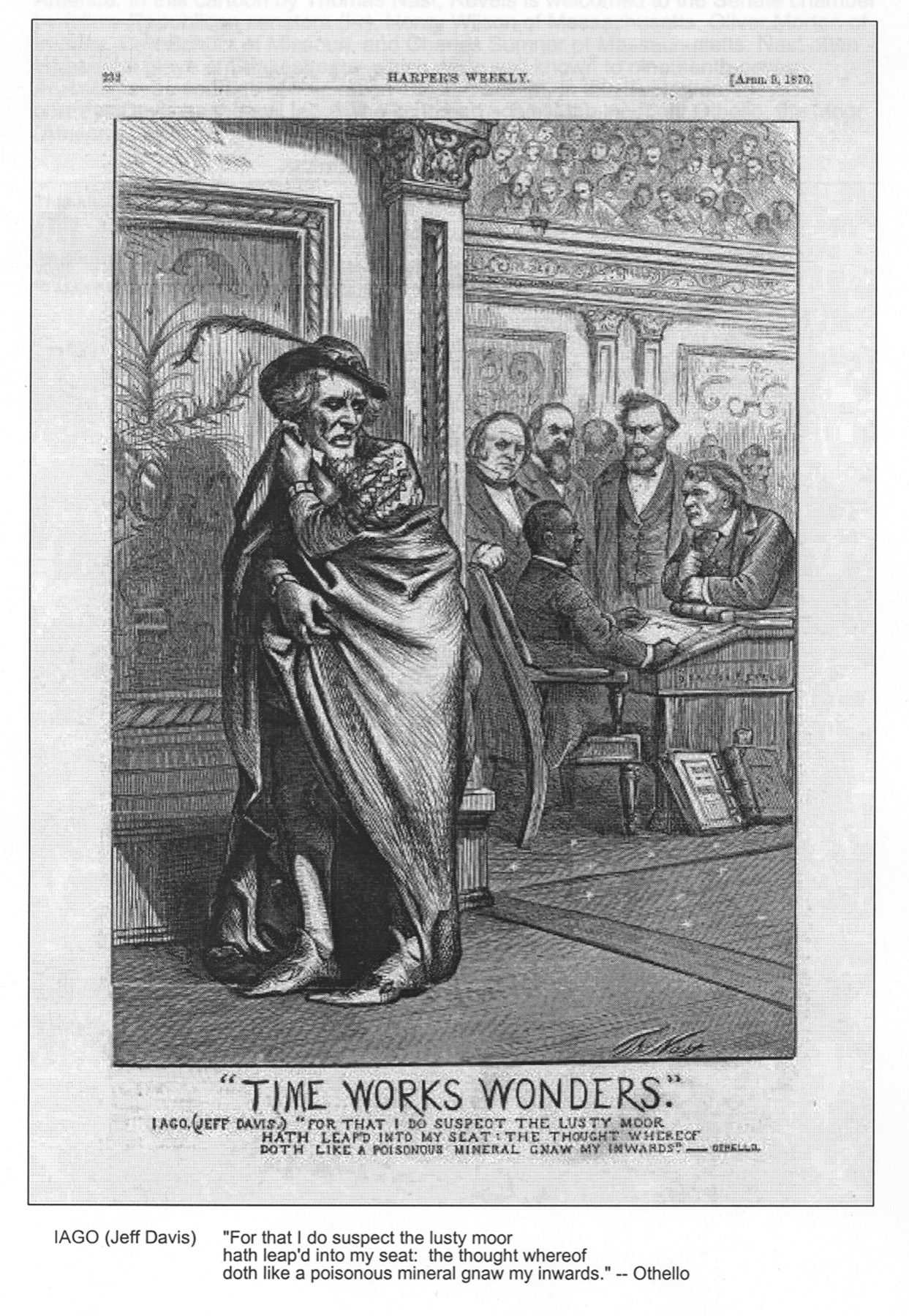

Cartoons & Articles: Black Voting Rights: The Creation of the Fifteenth Amendment. Harper’s Weekly.

Book: Foner, Eric. Freedom’s Lawmakers: A Directory of Black Officeholders during Reconstruction. New York: Oxford University Press, 1993.

Book: Foner, Eric. Reconstruction (Updated Edition): America’s Unfinished Revolution 1863–1877. New York: Harper Collins, 2014.

Learning for Justice-Voting Rights Timeline

Many of the activities and performance tasks in this unit involve whole or small group discussion prompts. Prior to beginning a class discussion with students, make sure that you have established classroom expectations for behavior that are grounded in respect and empathy for all. Remind students of these expectations, particularly for sharing opinions with which others may not agree.

These topics may raise questions with students about the existence of “unjust laws” and the role of government in perpetuating and codifying racist attitudes and structures. Throughout the lesson, students will encounter examples of ways recently freed African Americans had their civil rights withheld or restricted through legislative means. They will also encounter the language used by those who justified these decisions based on racist attitudes. Teaching students about the way laws have been used to enable racial inequality entails asking them to confront the way power and government may be misused. Successfully broaching such emotionally-charged content requires understanding your students, their intellectual and emotional needs, and engaging with history with empathy and care.

Within the activities there are sources that include racist language or images that need to be treated with sensitivity. These historical expressions of racism are included in order to help students recognize and understand the ongoing influence of White supremacist ideology after enslavement. However, it is imperative that these be shared with students with great care, as they can trigger painful emotions in students, such as anger, sadness, fear, and shame. African American students may feel that their identity is under attack. Moreover, if not examined critically, these sources can perpetuate anti-Black ideas. Use the guidelines below when sharing racist content with students.

When the Civil War ended in April 1865, the fate of the newly emancipated, or freed, African Americans was uncertain. The freedpeople themselves championed for their full rights as citizens. However, at first full citizenship seemed unlikely.

After Lincoln was assassinated, Vice President Andrew Johnson became president. Johnson began to lead the process of Reconstruction, or rebuilding society in the former Confederate states. Johnson was both conservative and stubborn. He did not consult Congress on his plan. He permitted the former Confederate states to re-enter the Union without changing who held power in the state. Believing that “white men alone must manage the South,” he made no arrangements for African Americans in former Confederate states to gain civil rights such as the right to vote.

Under Johnson’s plan for Reconstruction, many officials who had once served in the rebel government were reelected to the newly reconstructed state governments, including nine former Confederate congressmen. Worse yet, the new state governments of 1865-66 drafted a series of laws, known as the Black Codes, which severely limited the civil rights of the freedpeople. African Americans could be forced to work with little control over the hours and terms of their labor. They were also forbidden from serving on juries and had little access to the courts.

Republicans in Congress began to worry about these developments. If the freedpeople were denied their civil rights – if their contracts were not respected and they had no way to sue if they were not paid their wage – then was the Thirteenth Amendment abolishing slavery of any use? Didn’t the freedpeople remain enslaved in all but name? To many in Congress, the Confederates seemed to be winning in peace what they had lost in war.

Some members of the Republican party, which was founded in the 1850s as a party opposed to the expansion of slavery, believed strongly in the rights of African Americans. Other Republicans had a growing belief that their grip on Congress was tenuous and that the enfranchisement of African Americans was the way to gain political support. Though different, these two beliefs brought Republicans together and led them to join forces with African Americans in taking measures to ensure male suffrage. Republicans joined forces with African Americans and, despite initial hesitation, took steps to ensure Black men’s right to vote. (Women gained the right to vote when the Nineteenth Amendment was ratified, or made into law, in 1920.)

Select the activities and sources you would like to include in the student view and click “Launch Student View.”

It is highly recommended that you review the Teaching Tips and sources before selecting the activities to best meet the needs and readiness of your students. Activities may utilize resources or primary sources that contain historical expressions of racism, outdated language or racial slurs.

Begin this activity by asking students to share responses to a “Do Now” question. What requirements, if any, are there to vote in the United States today? Responses may vary somewhat by state but should include:

Inform or review with students that despite these current requirements that over the course of United States history, many groups of people did not have the right to vote and that some Americans still cannot vote.

Introduce to students that in order to explore and visualize the historical milestones and struggles different groups have experienced they will each contribute to the creation of a Voting Rights timeline. If time does not allow for students to create the timeline you can provide a timeline to students for review.

Divide students as desired and assign each a group that was not initially allowed to vote in America or had inequitable barriers to voting. Students should independently research using sources of your choosing to identify key events and key legislation dates leading up to federal suffrage interventions. As time allows, students can also identify key figures or movements. Groups include:

Reconvene the class and invite students to share their findings in order to construct a visual anchor chart. Students should then review the chart and share noticings and wonderings with the group. As a final discussion question, discuss with students responses to the following questions.

If not already provided, distribute the Student Context to students in order to ensure they understand the impact of Reconstruction on the expected outcomes of the Civil War. Then, as a class, read Frederick Douglass’s, “Reconstruction.” Because it is a difficult document, it may be best to have a different student read each paragraph aloud to the class and then clarify its meaning.

While reading the article, discuss the questions below as a whole group or through a Turn, Pair, Share structure:

Frederick Douglass, a great abolitionist and orator who was born into slavery and successfully sought his own freedom, wrote this article for a national magazine in 1866. Congress had already passed (over conservative President Andrew Johnson’s vetoes) two measures designed to help protect the civil rights of the freedspeople from the depredations of their former enslavers: the Civil Rights Bill of 1866, which wrote protections of African Americans’ civil rights into law; and the Freedmen’s Bureau Bill, which extended the life of a federal agency designed to oversee the reconstitution of the southern labor system. At the same time, Congress had drafted the 14th Amendment, which was designed to ensure the constitutionality of the Civil Rights Act of 1866. The 14th Amendment was not ratified until 1868. The 15th Amendment, guaranteeing voting rights to all men, regardless of race, color, or previous condition of servitude was not proposed to Congress until February 26, 1869.

_______________________________________________________________________________________

Whether the tremendous war so heroically fought and so victoriously ended shall pass into history a miserable failure, barren of permanent results; . . . or whether, on the other hand, we shall, as the rightful reward of victory over treason, have a solid nation, entirely delivered from all contradictions and social antagonisms, based upon loyalty, liberty, and equality, must be determined one way or the other by the present session of Congress.

The last session [of Congress] really did nothing which can be considered final as to these questions. The Civil Rights Bill and the Freedmen's Bureau Bill and the proposed constitutional amendments, with the amendment already adopted and recognized as the law of the land, do not reach the difficulty, and cannot, unless the whole structure of the government is changed from a government by States to something like a despotic central government, with power to control even the municipal regulations of States, and to make them conform to its own despotic will.

While there remains such an idea as the right of each State to control its own local affairs – an idea, by the way, more deeply rooted in the minds of men of all sections of the country than perhaps any one other political idea – no general assertion of human rights can be of any practical value. To change the character of the government at this point is neither possible nor desirable. All that is necessary to be done is to make the government consistent with itself, and render the rights of the States compatible with the sacred rights of human nature.

The arm of the Federal government is long, but it is far too short to protect the rights of individuals in the interior of distant States. They must have the power to protect themselves, or they will go unprotected, spite of all the laws the Federal government can put upon the national statute-book. . . .

The policy that emancipated and armed the negro – now seen to have been wise and proper by the dullest – was not certainly more sternly demanded than is now the policy of enfranchisement. If with the negro was success in war, and without him failure, so in peace it will be found that the nation must fall or flourish with the negro.

Fortunately, the Constitution of the United States knows no distinction between citizens on account of color. Neither does it know any difference between a citizen of a State and a citizen of the United States. Citizenship evidently includes all the rights of citizens, whether State or national. If the Constitution knows none, it is clearly no part of the duty of a Republican Congress now to institute one. The mistake of the last session was the attempt to do this very thing, by a renunciation of its power to secure political rights to any class of citizens, with the obvious purpose to allow the rebellious States to disfranchise, if they should see fit, their colored citizens. This unfortunate blunder must now be retrieved, and the emasculated citizenship given to the negro supplanted by that contemplated in the Constitution of the United States, which declares that the citizens of each State shall enjoy all the rights and immunities of citizens of the several States, so that a legal voter in any State shall be a legal voter in all the States.

Document 4.15.1: Excerpt from Frederick Douglass, “Reconstruction” (1866)

If not already provided, distribute the Student Context to students in order to ensure they understand the impact of Reconstruction on the expected outcomes of the Civil War. Then, as a class, read or review Frederick Douglass’s “Reconstruction.” Because it is a difficult document, it may be best to have a different student read each paragraph aloud to the class and then clarify its meaning. For students *Gr.5 + you may want to summarize and then review the quote provided.

As a whole class discussion or an individual response ask students to consider the validity of Douglas’s words in the present day in relation to current events.

“The arm of the Federal government is long, but it is far too short to protect the rights of individuals in the interior of distant States. They must have the power to protect themselves, or they will go unprotected…”

Frederick Douglass, a great abolitionist and orator who was born into slavery and successfully sought his own freedom, wrote this article for a national magazine in 1866. Congress had already passed (over conservative President Andrew Johnson’s vetoes) two measures designed to help protect the civil rights of the freedspeople from the depredations of their former enslavers: the Civil Rights Bill of 1866, which wrote protections of African Americans’ civil rights into law; and the Freedmen’s Bureau Bill, which extended the life of a federal agency designed to oversee the reconstitution of the southern labor system. At the same time, Congress had drafted the 14th Amendment, which was designed to ensure the constitutionality of the Civil Rights Act of 1866. The 14th Amendment was not ratified until 1868. The 15th Amendment, guaranteeing voting rights to all men, regardless of race, color, or previous condition of servitude was not proposed to Congress until February 26, 1869.

_______________________________________________________________________________________

Whether the tremendous war so heroically fought and so victoriously ended shall pass into history a miserable failure, barren of permanent results; . . . or whether, on the other hand, we shall, as the rightful reward of victory over treason, have a solid nation, entirely delivered from all contradictions and social antagonisms, based upon loyalty, liberty, and equality, must be determined one way or the other by the present session of Congress.

The last session [of Congress] really did nothing which can be considered final as to these questions. The Civil Rights Bill and the Freedmen's Bureau Bill and the proposed constitutional amendments, with the amendment already adopted and recognized as the law of the land, do not reach the difficulty, and cannot, unless the whole structure of the government is changed from a government by States to something like a despotic central government, with power to control even the municipal regulations of States, and to make them conform to its own despotic will.

While there remains such an idea as the right of each State to control its own local affairs – an idea, by the way, more deeply rooted in the minds of men of all sections of the country than perhaps any one other political idea – no general assertion of human rights can be of any practical value. To change the character of the government at this point is neither possible nor desirable. All that is necessary to be done is to make the government consistent with itself, and render the rights of the States compatible with the sacred rights of human nature.

The arm of the Federal government is long, but it is far too short to protect the rights of individuals in the interior of distant States. They must have the power to protect themselves, or they will go unprotected, spite of all the laws the Federal government can put upon the national statute-book. . . .

The policy that emancipated and armed the negro – now seen to have been wise and proper by the dullest – was not certainly more sternly demanded than is now the policy of enfranchisement. If with the negro was success in war, and without him failure, so in peace it will be found that the nation must fall or flourish with the negro.

Fortunately, the Constitution of the United States knows no distinction between citizens on account of color. Neither does it know any difference between a citizen of a State and a citizen of the United States. Citizenship evidently includes all the rights of citizens, whether State or national. If the Constitution knows none, it is clearly no part of the duty of a Republican Congress now to institute one. The mistake of the last session was the attempt to do this very thing, by a renunciation of its power to secure political rights to any class of citizens, with the obvious purpose to allow the rebellious States to disfranchise, if they should see fit, their colored citizens. This unfortunate blunder must now be retrieved, and the emasculated citizenship given to the negro supplanted by that contemplated in the Constitution of the United States, which declares that the citizens of each State shall enjoy all the rights and immunities of citizens of the several States, so that a legal voter in any State shall be a legal voter in all the States.

Document 4.15.1: Excerpt from Frederick Douglass, “Reconstruction” (1866)

Begin this activity by introducing students to Carl Schurz.

Carl Schurz was a prominent politician during the 19th century. Schurz became active in politics and the abolitionist movement when he joined the newly formed Republican Party and campaigned for Abraham Lincoln in the 1860 presidential election. Schurz was also a well known military figure. During the Civil War, he served as a Union Army general and played a key role in several battles. Following the war, Schurz became a Senator for Missouri from 1869-1875.

Then have students read Carl Schurz’s letter to President Andrew Johnson.

As time allows, have students complete the Compare and Contrast Chart to record similarities and differences between the excerpt from Activity 1 from Frederick Douglass and this expert from Schurz.

Ask students the following questions:

Frederick Douglass, a great abolitionist and orator who was born into slavery and successfully sought his own freedom, wrote this article for a national magazine in 1866. Congress had already passed (over conservative President Andrew Johnson’s vetoes) two measures designed to help protect the civil rights of the freedspeople from the depredations of their former enslavers: the Civil Rights Bill of 1866, which wrote protections of African Americans’ civil rights into law; and the Freedmen’s Bureau Bill, which extended the life of a federal agency designed to oversee the reconstitution of the southern labor system. At the same time, Congress had drafted the 14th Amendment, which was designed to ensure the constitutionality of the Civil Rights Act of 1866. The 14th Amendment was not ratified until 1868. The 15th Amendment, guaranteeing voting rights to all men, regardless of race, color, or previous condition of servitude was not proposed to Congress until February 26, 1869.

_______________________________________________________________________________________

Whether the tremendous war so heroically fought and so victoriously ended shall pass into history a miserable failure, barren of permanent results; . . . or whether, on the other hand, we shall, as the rightful reward of victory over treason, have a solid nation, entirely delivered from all contradictions and social antagonisms, based upon loyalty, liberty, and equality, must be determined one way or the other by the present session of Congress.

The last session [of Congress] really did nothing which can be considered final as to these questions. The Civil Rights Bill and the Freedmen's Bureau Bill and the proposed constitutional amendments, with the amendment already adopted and recognized as the law of the land, do not reach the difficulty, and cannot, unless the whole structure of the government is changed from a government by States to something like a despotic central government, with power to control even the municipal regulations of States, and to make them conform to its own despotic will.

While there remains such an idea as the right of each State to control its own local affairs – an idea, by the way, more deeply rooted in the minds of men of all sections of the country than perhaps any one other political idea – no general assertion of human rights can be of any practical value. To change the character of the government at this point is neither possible nor desirable. All that is necessary to be done is to make the government consistent with itself, and render the rights of the States compatible with the sacred rights of human nature.

The arm of the Federal government is long, but it is far too short to protect the rights of individuals in the interior of distant States. They must have the power to protect themselves, or they will go unprotected, spite of all the laws the Federal government can put upon the national statute-book. . . .

The policy that emancipated and armed the negro – now seen to have been wise and proper by the dullest – was not certainly more sternly demanded than is now the policy of enfranchisement. If with the negro was success in war, and without him failure, so in peace it will be found that the nation must fall or flourish with the negro.

Fortunately, the Constitution of the United States knows no distinction between citizens on account of color. Neither does it know any difference between a citizen of a State and a citizen of the United States. Citizenship evidently includes all the rights of citizens, whether State or national. If the Constitution knows none, it is clearly no part of the duty of a Republican Congress now to institute one. The mistake of the last session was the attempt to do this very thing, by a renunciation of its power to secure political rights to any class of citizens, with the obvious purpose to allow the rebellious States to disfranchise, if they should see fit, their colored citizens. This unfortunate blunder must now be retrieved, and the emasculated citizenship given to the negro supplanted by that contemplated in the Constitution of the United States, which declares that the citizens of each State shall enjoy all the rights and immunities of citizens of the several States, so that a legal voter in any State shall be a legal voter in all the States.

Document 4.15.1: Excerpt from Frederick Douglass, “Reconstruction” (1866)

In this document, Carl Schurz, a member of the moderate Liberal Republican faction, illustrates the competing imperatives facing Congressional Republicans after the Civil War. On the one hand, was an ardent belief in the principle of states’ rights federalism, or the notion that liberty is best protected by limited interference of the national government into state and local affairs – in Henry David Thoreau’s words, that “that government is best, which governs least.” On the other hand was the need to guarantee that the system of slavery would be abolished in practice as well as in law. In this letter to President Andrew Johnson, Schurz offers his solution to the dilemma.

_____________________________________________________________________________________

The interference of the national authority in the home concerns of the southern States would be rendered less necessary, and the whole problem of political and social reconstruction be much simplified, if, while the masses lately arrayed against the government are permitted to vote, the large majority of those who were always loyal . . . were not excluded from all influence upon legislation. . . . In the right to vote we would find the best permanent protection against oppressive class-legislation, as well as against individual persecution. . . . It is a notorious fact that the rights of a man of some political power are far less exposed to violation than those of one who is, in matter of public interest, completely subject to the will of others. . . . The effect of the extension of the franchise to the colored people upon the development of free labor and upon the security of human rights in the south being the principal object in view, the objections raised on the ground of the ignorance of the freedmen become unimportant.

Source: Carl Schurz to President Andrew Johnson, 1865, in Walter L. Fleming, ed., Documentary History of Reconstruction: Political, Military, Social, Religious, Educational and Industrial, 1865 to the Present Time (Cleveland: Arthur H. Clark, 1907), I, pp. 95-96.

Document 4.15.2: Carl Schurz’s letter to President Andrew Johnson, 1865

Explain to students that one of the key factors in granting African American men the right to vote was their important military service during the Civil War, where it is estimated that 180,000 Black soldiers fought for the Union. The Emancipation Proclamation, issued by President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863, specifically included a provision that allowed African Americans to serve in the Union Army and Navy. The Military Service Authorization declared that African American men would be accepted into military service for the Union forces. This authorization was a significant departure from previous federal policies that had excluded African Americans from military service.

Then, explain to students that they will be examining a political cartoon that appeared in Harper’s Weekly during Reconstruction which depicts an African American soldier. Have students complete the Political Cartoon Analysis handout. As a whole class discuss findings in relation to the right to vote afforded or not afforded to soldiers.

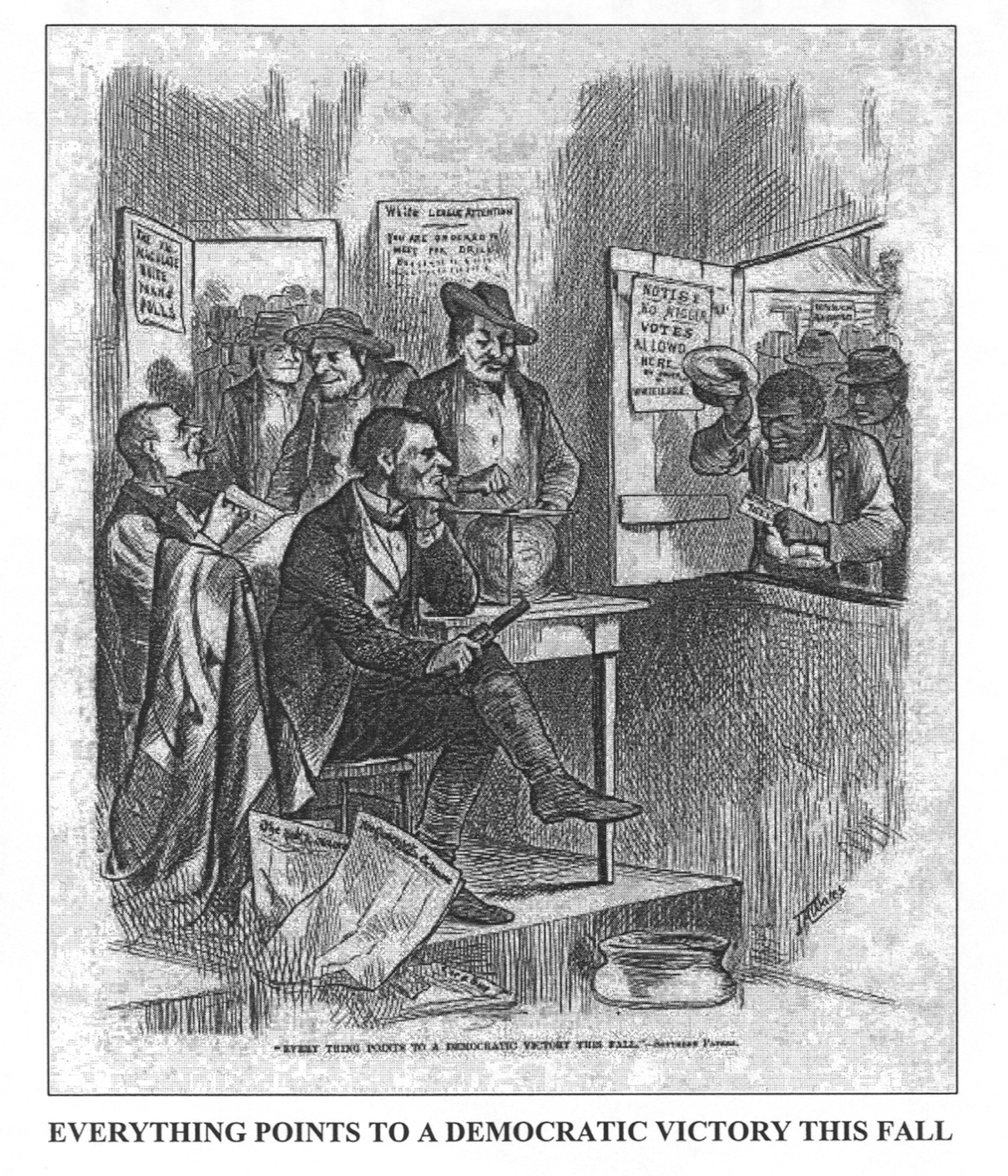

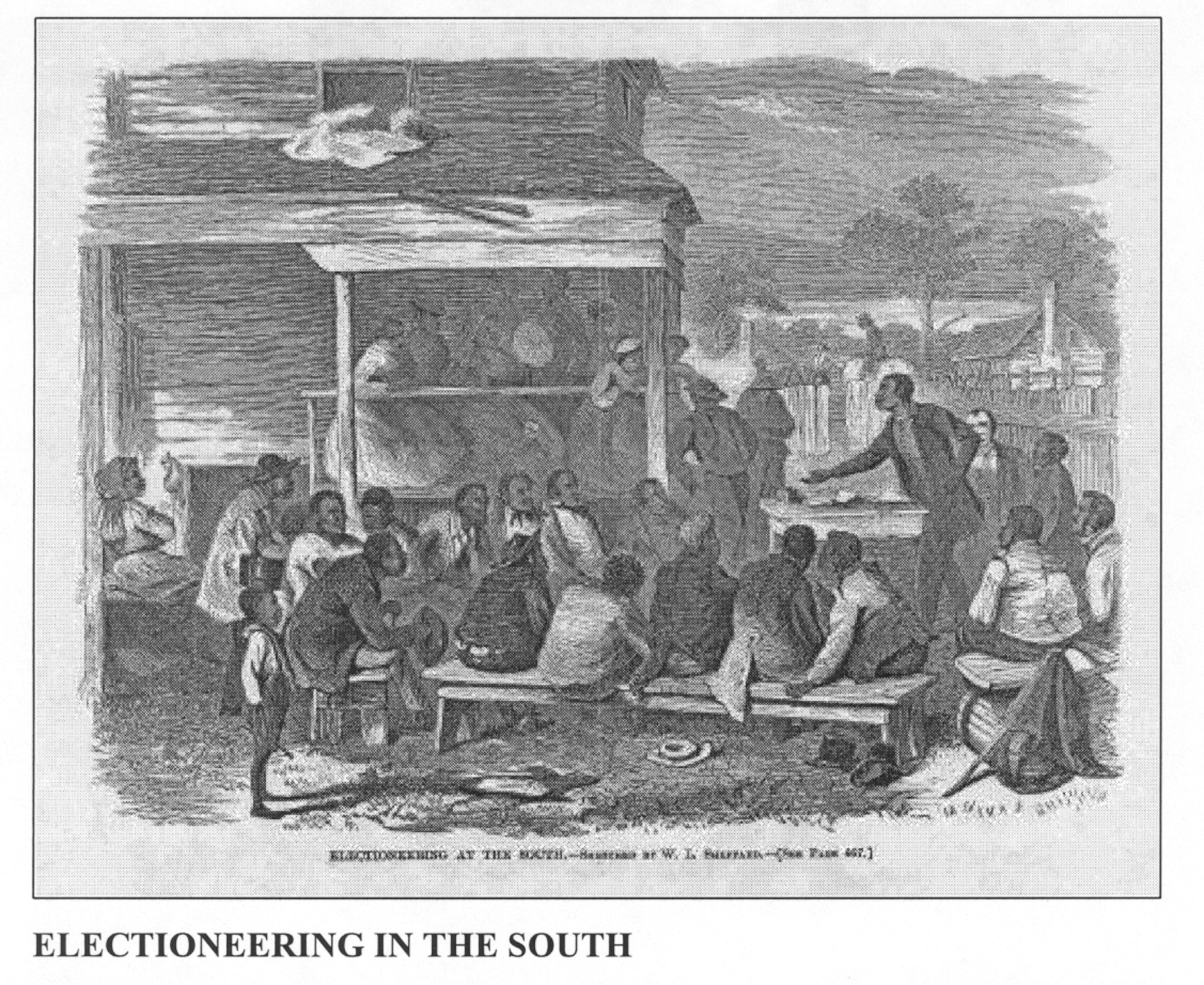

Then, explain to students that they will be examining a series of political cartoons that appeared in Harper’s Weekly during Reconstruction.

Divide students into small groups. Assign to each group the analysis of an image(s):

Have each group complete the Political Cartoon Analysis handout and/or respond to the questions below.

Upon completing the questions, each group should report to the class on the print it analyzed. (It is suggested that the prints should be reported on in their chronological order).

Next, have students examine “Everything Points to a Democratic Victory This Fall.” Note: This cartoon includes the N-word in the text. See the “Teaching Tips” section above for suggestions about how to handle content with racist language. As a class, consider the same set of questions included above.

Have the class attempt to outline the story of Black voting rights during Reconstruction as told through the prints.

Begin this activity by reviewing with the students The Military Reconstruction Acts.

Despite President Andrew Johnson’s opposition, the Republican-controlled Congress passed the Military Reconstruction Acts in 1867. Under these acts, the former Confederate states (except for Tennessee) were to be taken out of the Union and temporarily ruled by military governors. Each of the ten states had to hold a new constitutional convention. In order to be successful, African American men had to be able to vote for representatives at the new conventions. The new conventions had to: 1) create new state governments that abolished slavery; 2) ratify the Fourteenth Amendment guaranteeing citizenship rights to African Americans; and 3) provide for the enfranchisement, or voting rights, of Black men.

These new state governments became the nation’s first meaningful experiment in interracial (involving members of different racial groups) democracy. African Americans were represented through their votes, which tended to go to the Republican Party. They were also represented directly; for the first time, large numbers of African Americans were elected to office. In 1870, the Fifteenth amendment to the Constitution was ratified, making it illegal to deny men the vote on the basis of race.

Next, have students examine images that depict aspects of African American participation in the electoral process. Have each group complete the Political Cartoon Analysis handout and/or respond to the specific questions below.

“The First Colored Senator and Representatives” and “Radical Members” viewed together

Upon completing the questions, each group should report to the class on the print(s) it analyzed. Next, have students examine ““Colored Rule in a Reconstructed (?) State” as a whole class. Note:This cartoon includes racial stereotypes. See the “Teaching Tips” section above for suggestions about how to handle content with racist language. As a class, consider the Political Cartoon Analysis questions and/or respond to the following:

Examine “African American Officeholders in the Reconstruction South.” As a class, formulate several general statements about African-American officeholders, which the data support, and note them on the board.

Then, read the provided excerpt from James Shepherd Pike’s, The Prostrate State. This source includes racist language and caricatured depictions of Black legislators. See the “Teaching Tips” section above for suggestions about how to handle racist primary source content.

Discuss with the class:

Individually or in small groups, have students write a letter to James Shepherd Pike, responding to his description of the South Carolina legislature. Students should use data from the chart to support their points.

James Shepherd Pike was a journalist from New York City before the Civil War – a staunch antislavery man and ardent abolitionist who wrote for Horace Greeley’s liberal New York Tribune in the 1850s. During the Reconstruction, he put his journalistic skills to work documenting the progress of Reconstruction. He traveled to South Carolina, one of the few southern state legislatures where African Americans constituted a notable political force. Curiously, his pre-war sympathies transformed completely, and he became a staunch supporter of White rule in the South. Published as The Prostrate State in 1874, his account of Black participation in the South Carolina state legislature was not so much the cause of his conversion to White supremacy so much as evidence that it has already been completed. His account served as the basis for later racist diatribes such as Thomas Dixon’s novel The Clansman (1905) and the film The Birth of a Nation (1915).

_____________________________________________________________________________________

Yesterday, about 4 p.m., the assembled wisdom of the State . . . issued forth from the State-House. About three-quarters of the crowd belonged to the African race. They were of every hue, from the light octoroon to the deep black. . . .

Let us approach nearer and take a closer view. We will enter the [South Carolina] House of Representatives. . . . The Speaker is black, the Clerk is black, the chairman of the Ways and Means is black, and the chaplain is coal-black. At some of the desks sit colored men whose types it would be hard to find outside of Congo; whose costume, visages, attitudes, and expression, only befit the forecastle of a buccaneer. It must be remembered, also, that these men, with not more than half a dozen exceptions, have been themselves slaves, and that their ancestors were slaves for generations. . . .

One of the things that first strike a casual observer in this negro assembly is the fluency of debate, if the endless chatter that goes on there can be dignified with this term. . . . Sambo can talk on these topics and those of a kindred character, and their endless ramifications, day in and day out. . . . The negro is imitative in the extreme. He can copy like a parrot or a monkey. . . . His misuse of language in his imitations is at times ludicrous beyond measure. . . .

Here, then, is the outcome, the ripe, perfected fruit of the boasted civilization of the South after two hundred years of experience. A white community that had gradually risen from small beginnings till it grew into wealth, culture, and refinement, and became accomplished in all the arts of civilization. . . . It lies prostrate in the dust, ruled over by this strange conglomerate, gathered from the ranks of its own servile population. It is the spectacle of a society turned bottom-side up. . . . It is the slave rioting in the halls of his master and putting that master under his feet. . . . Does anybody suppose that such a condition of things as exists to-day in South Carolina is to last?

Source: James S. Pike, The Prostrate State: South Carolina Under Negro Government (New York: D. Appleton and Co., 1874), 9-21, 58-65.

Document 4.15.12: Excerpts from The Prostrate State by James Shepherd Pike, 1874.

Introduce the Fall of Reconstruction governments to students by sharing a desired text resource or sharing the following brief overview:

The Republican state governments in the South were met by a strong backlash. Former Confederates and White supremacists attacked them immediately, targeting African American voters and politicians in particular. Southern Democrats and their supporters claimed that the presence of “ignorant” formerly enslaved people in the voting populace led to a “tragic era” of corruption and misrule. A concerted campaign of voting fraud, terror, and violence led up to the presidential election of 1876.

In the 1876 election, Rutherford Hayes was the Republican candidate and Samuel Tilden was the Democratic candidate. The results of the election were contested and Hayes agreed to the Compromise of 1877, also known as the Hayes-Tilden Compromise or the Electoral Commission Act. The compromise was a series of informal agreements and understandings reached between representatives of the Republican and Democratic parties. Under this compromise, Hayes would be awarded the presidency. In return, Hayes agreed to several concessions sought by Southern Democrats, including the withdrawal of federal troops from the South and an end to federal intervention in Southern state politics. The withdrawal of federal troops allowed Southern Democrats to regain control of state governments across the South.

As a whole group discuss the following questions.

Next, show students the image of Compromise with the South by Thomas Nast. As a whole group discuss the following questions.

Introduce to students that in the fabric of every society, the role of government stands as a pivotal force that shapes the collective well-being and progress of its citizens. Therefore, understanding the dynamics of governmental roles, input and functions is a critical exploration into how societies are organized, governed, and ultimately thrive or falter. Ask students to select an essay in which they address one or more of the following questions.

Please login or sign up to access the student view functions.